Ch. 26 - Opioids

Eleni K. Horattas, MD; Kristopher M. Carbone, MSBS, MS, MD; Brittany CH Koy, MD

America’s New Epidemic

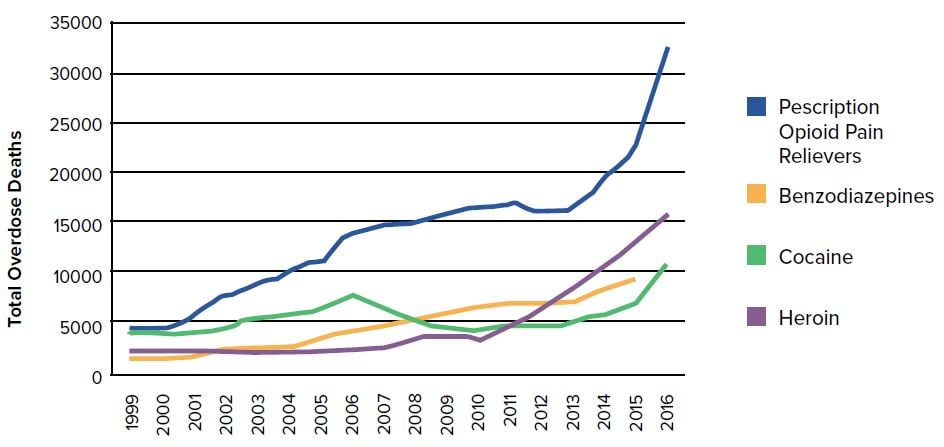

In the 1980s, an expert in the field of pain management, Dr. Russell Portenoy, brought attention to opioids as an option for non-cancer pain control, portraying it as a medication without significant risk of addiction.1 Pharmaceutical companies propagated this stance with aggressive marketing and continued downplaying risks, while emphasis on pain control grabbed the attention of regulatory bodies (including The Joint Commission), resulting in hospitals focusing on pain as the “fifth vital sign.”2 The unintended consequences of this movement have resulted in an epidemic of opioid use in America. ACEP has recognized the opioid epidemic as “one of the most devastating public health crises in a generation.”3 Despite the opioid epidemic being a front-page topic, in both the medical field and media outlets, CDC data shows the U.S. opioid overdose epidemic continues to worsen (Figure 26.1).

Emergency physicians serving on the front lines are seeing patients with opioid addiction, often in their darkest hours.

FIGURE 26.1. Overdose Deaths per Year by Drug Substance3-5

Emergency Medicine Providers Face Difficult Decisions

Data shows opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits have increased for both sexes and all age groups, showing no patient population has been left untouched by this health crisis.6 Nationally, the rate of opioid-related inpatient stays has increased by 64% and opioid-related ED visits doubled.6

Large-scale analyses have shown that in 2012 alone, 259 million prescriptions for opioid pain medications were written by medical providers.7 While pain control is a frequent reason for presentation to the ED, it is crucial to note that the same analyses found less than 5% of the nation’s total opioid pain pills were prescribed by emergency physicians.7 In one study that reviewed more than 27,000 ED visits, only 17% of discharged patients received prescriptions for opiate medications.7

Emergency physicians serving on the front lines are seeing these patients with addiction, often in their darkest hours. The CDC published data regarding opiate prescribing among all physician providers, which showed more than 19% reduction from 2006 to 2017, with a peak in 2012 of highest prescribing rates.8 Emergency physicians are becoming increasingly educated regarding risks associated with prescription opiate use and are showing awareness and balance between exercising appropriate caution in providing these medications, while still attempting to provide adequate pain control for our patients.7

Medication-Assisted Treatment and Its Implementation in the ED

For patients suffering from addiction and opioid use disorder (OUD), the emergency physician may be the only physician they regularly encounter, and it is crucial for EM providers to understand treatment guidelines for opioid addiction. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) combines behavioral therapy and medications to treat substance use disorders.9 This process utilizes U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medications in combination with counseling, with the goal of targeting a “whole-patient” approach to treatment of substance use disorders. Currently, there are three commonly used medications: methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine. The prescribed medication helps to block the euphoric effects of the abused drug, relieve physiologic craving, and normalize body functions without the negative effects and risks of the abused drug. All patients enrolled in MAT are required to receive counseling. Treatment programs are approved and regulated by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, structured by federal legislation, regulations, and guidelines.10 Research assessing effectiveness of MAT has demonstrated significant results, showing increased likelihood of patients avoiding relapse, improved overall social functioning, and reduced risk of infectious disease transmission and engagement in criminal activities.11 A study looking at heroin overdose-related deaths in Baltimore between 1995–2009 found approximately 50% decrease in fatal overdoses associated with increased availability of methadone and buprenorphine.12

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 permits physicians who meet specific criteria to treat opioid use disorder with schedule III-V controlled substances (such as buprenorphine and suboxone) in settings outside of opioid treatment programs. In general, a practitioner who dispenses scheduled medications for maintenance of detoxification must be separately registered as a narcotic treatment program as per the Narcotic Addict Treatment Act of 1974.12 This registration and separate licensing allows the practitioner to dispense, but not prescribe these medications. An exception to separate licensing is what is known as the “3 Day Rule,” or 72-hour rule.13 This allows a provider who is not separately registered as a treatment program to administer, but not prescribe, the narcotic

medication in an emergency setting. This medication is administered to the patient with the goal of relieving acute withdrawal symptoms, in conjunction with referral for further treatment. Restrictions do remain, in that no more than one day’s worth of medication may be administered to the patient at one single time. This treatment cannot extend for greater than 72 hours, and the 72-hour time period cannot be extended or renewed. Randomized clinical trial data has shown that ED-initiated buprenorphine treatment, with coordinated outpatient follow-up for ongoing treatment, resulted in a greater percentage of patients remaining in treatment with fewer self-reported days of illicit drug use when compared to ED referral only (with or without brief intervention).13 Traditionally, patients with

OUD or those treated for overdose are discharged with follow up information for addiction resources, with impending or ongoing opiate withdrawal symptoms. Emergency physicians who administer ED-initiated MAT, may alleviate withdrawal symptoms, as well as offering patients motivation through a positive interaction with health care providers and a first step toward forming a plan for recovery.

Monitoring Programs and State Legislation Regarding Opiate Prescribing

Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) were created as early as 1940 in California. These programs have recently become more prevalent, with 49 of 50 states now fully participating in hopes of detecting and monitoring high-risk prescribing and patient behaviors. While these programs vary across state lines regarding design, inclusion of selected controlled substance schedules, and how data is collected and reported, the common goal of all PDMPs is to reduce prescription drug diversion and abuse.

Missouri, despite having a PDMP developed in 2017 at the order of the governor, lacks proper funding, as state lawmakers have attempted to defund the program due to concerns that primary goal of the Missouri PDMP is to investigate and punish prescribers and pharmacists, rather than allowing providers to monitor patient behaviors.14

A study reported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse found an average reduction of 1.12 opioid-related overdose deaths per 100,000 persons, within one year of a given state’s PDMP implementation.15 While there has been proven benefit to instituting PDMPs, limitations have also been recognized.16 EM providers have identified that while the goal of PDMPs is to aid in medical decision making and prescribing, access can be a restrictive factor in that it can be time consuming and take away from bedside patient care. Thirty-five states mandate the use of PDMPs in specific contexts. Studies have shown that the mandated use of PDMPs did not significantly decrease opioid prescribing of EM providers, when compared to mandated registration and allowing providers to access the data at their discretion.16

Individual state legislation has placed further limitations on the prescribing of opiate medications by physicians. Federal law does not impose prescribing restrictions on duration or quantity of supply of controlled substances, however 18 states currently have legislation restricting prescribing practices.17 While there has been a reduction in opioid prescribing with this regulation, there is concern amongst providers that proper exceptions have not been instated for populations at risk for being undertreated, include but not limited to hospice and palliative patients.

Naloxone

Naloxone is an opioid receptor antagonist, a medication that can rapidly reverse the respiratory and CNS depression seen in opioid overdoses. The FDA classifies naloxone as a prescription medication, however in light of the opioid epidemic, health care providers have identified the critical role layperson naloxone administration has played in mortality reduction.18 Individual states control access to this medication, some of which have permitted over the counter distribution by health departments and pharmacies. In patients identified as “high-risk” for misuse or abuse of opioid medications, naloxone is becoming a more frequently prescribed home medication by health care providers, including emergency physicians. While lives have been saved by EMS and family member administration of naloxone, there remains the debate of legal liability. As outlined in the Model Naloxone Access Act by National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws, ACEP supports legislation to protect health care providers and civilians

from “civil, professional, and criminal liability for failure or misuse of bystander naloxone.”19

Federal Action

On October 26, 2017, the HHS Secretary declared the opioid epidemic to be a national public health emergency.20 While the opioid crisis had been ongoing for years, opioid-related overdoses had increased by nearly 30% from 2016 to 2017.21 This increase provided some of the driving force for stronger preventative measures to protect patients from not only the risk of opioid prescribing, but to provide patients who had developed dependence and addiction with a way to gain access to resources to prevent future overdoses. Realizing that the ED was on the forefront of these issues in the opioid crisis, Dr. Mark Rosenberg and other members of the ACEP Board of Directors decided it was imperative to advocate for legislation that could affect ED patients on a national scale. With

the experience gained by Dr. Rosenberg at his home institution in New Jersey in developing an alternative to opioids (ALTO) program and a MAT program for those seeking addiction treatment from the ED, two bills were introduced into congress to address this important national issue.22 These two bills were eventually integrated into the “Opioid Crisis Response Act” and signed into law in October 201827,28,29

The Preventing Overdoses While in the Emergency Room Act (POWER Act23) will help families and patients who are at high risk for opioid abuse to gain access to life saving medications, such as naloxone, as well as provide an infrastructure to those patients seeking treatment in the ED due to significant opioid dependence and addiction. It will allow for grants to institutions to not only establish MAT, but also to develop infrastructure in assessing and coordinating care of these patients through processes such as the “warm handoff.” These “warm handoff” programs are being implemented in order to recognize and refer patients with OUD directly from the ED for appropriate outpatient or inpatient behavioral therapy follow-up. For example, in the state of Pennsylvania through

the Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs in cooperation with the DOH, they have developed a flow chart that helps EM providers to recognize and risk stratify these patients. They can then either admit these patients where this warm handoff assessment would continue, or discharge the patients with lifesaving medications and referral for outpatient treatment after assessment by a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Specialist, and communicating to their PMD or other appropriate Substance Use Disorder Specialist to ensure outpatient followup and MAT.24,25

The second bill, the ALTO Act26, will address the primary prevention of opioid addiction by helping to fund and develop programs that treat acute and chronic pain in the ED without the use of opioids. Programs like these have alreadybeen instituted in some states such as Colorado, where they have been able to demonstrate a reduction of approximately 36% in opioid prescribing.22

ACEP Advocates for Harm Reduction

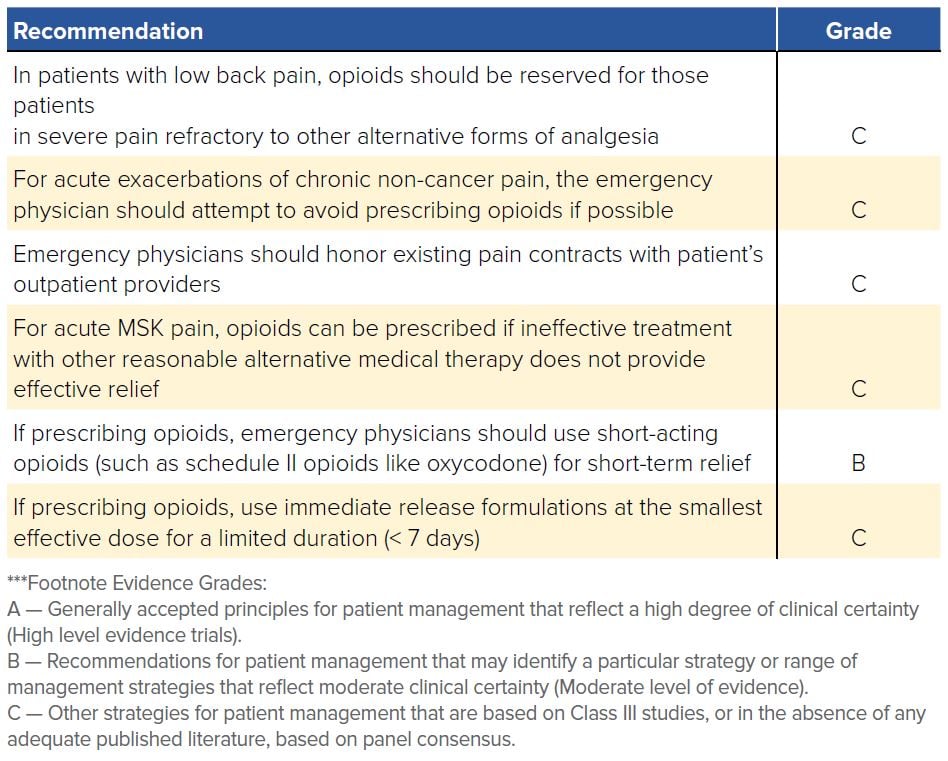

As emergency physicians we routinely deal with acute injuries and illness as well as acute exacerbations of chronic conditions that cause our patients pain. It is our duty as physicians to attempt to relieve suffering in a reasonable way. In June 2012, ACEP released a Clinical Policy on “Issues in the Prescribing of Opioids for Adult Patients in the Emergency Department,” including a number of evidence-based recommendations on the prescribing of opioids in the ED for adult patients with non-cancer related pain.30 Following suit, many state ACEP chapters, such as Colorado, have also developed their own recommendations on pain treatment and opioid prescribing in the ED.31

FIGURE 26.2. Recommendations for Prescribing Opioids in the ED30

ACEP and other physician-led organizations have recognized the threat of opioid misuse and addiction and led the charge in battling this terrible epidemic. However, there is still much to learn and do in order to protect our patients from the dangers of opioids, while still providing adequate pain control for emergent conditions.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- When you treat patients at high risk of opioid overdose, consider prescribing naloxone to prevent fatal overdoses.

- Support state and federal legislation that would improve the ability of emergency physicians to initiate appropriate treatment in the ED for patients with opioid use disorder.

- Investigate the policies in your ED and the resources available in your community for the treatment of patients with opioid use disorder.

- Make sure that you are registered for your state’s PDMP, and advocate for reasonable state laws surrounding PDMP usage.