Ch. 24 - Mental Health in the ED

Jonathan W. Meadows, DO, MS, MPH, CPH; Veronica Tucci, MD, JD, FACEP

The landscape of mental health services has drastically evolved over the past two centuries. Once centered on the asylum (theorized as a protected sanctuary for longterm psychiatric care) and the long-term institutionalized care of patients with the most severe and chronic mental health problems, several key events — from transinstitutionalization to deinstitutionalization to the rise of pharmaceutical therapies — shifted care to the outpatient setting.1 The U.S. mental health system has become more community-based, decentralized, heterogeneous, and fragmented, leading to an array of outpatient services and more episodic treatment.1 Although this has facilitated improved access for patients with minor to moderate mental health conditions, the number of patients requiring acute

stabilization and intervention has overwhelmed most available mental health access points, leaving those in crisis with no alternative but to seek care at overburdened emergency departments. This, coupled with dwindling psychiatric hospital beds, has created a mental health care crisis in the U.S.

Emergency physicians should work to improve outpatient access, reduce regulatory barriers to integrated health, and provide additional resources for mental health treatment.

Psychiatric beds nationwide dropped from approximately 400,000 in 1970 to 50,000 in 2006, with 80% of states reporting a shortage of beds.2,3 In 2015, the U.S. ranked 30th of the 34 OECD countries reporting the number of psychiatric care beds in hospitals per 1,000 persons. The U.S. reported 0.21, while New Zealand was 0.24, Great Britain 0.42, Belgium 1.4, and Japan ranked the highest with 2.65.4 Whether due to the long-term effects of deinstitutionalization, inadequate community resources, the large numbers of uninsured patients, or other causes, the number of patients in psychiatric crisis presenting to EDs is on the rise and trending upward.5 Between 2006 and 2013, the rate of ED visits for depression, anxiety and stress reactions increased 55% and the rate for

psychoses and bipolar disorder increased 52%.6

Incarceration of the Mentally Ill

Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics from 2011–2017 illustrated that 37% of state and federal prisoners and 44% of local jail inmates had a mental disorder.7 Research suggests that “people with mental illnesses are overrepresented in probation and parole populations at estimated rates ranging from two to four times the general population.”8 This has caused significant strain on U.S. law enforcement agencies and correctional facilities for several reasons and has been part of a growing trend of “transinstitutionalization.”1 First, individuals with mental illness are jailed on average 2–3 times longer than individuals without a mental illness arrested for a similar crime.9 Next, jails incur significant costs associated with the oversight of mental health prisoners for medication and other health care services.9 Lastly, these inmates have very little chance of rehabilitation while incarcerated without proper psychiatric care; this increases the likelihood they will remain a danger to society or become repeat offenders. Moreover, a stay in jail may even exacerbate the person’s illness, and at the very least tarnish their public record, making it more difficult to regain employment and reintegrate back into society.9

Medication non-compliance is one major reason psychiatric patients decompensate and begin acting erratically and/or commit crimes. One study showed that monthly medication possession and receipt of outpatient services reduced the likelihood of any arrests.10 This study further concluded there was “an additional protective effect against arrest for individuals in possession of their prescribed pharmacological medications for 90 days after hospital discharge.”10 Thus, increasing community access to outpatient psychiatric services after incarceration for medication management should be a cornerstone of mental health reform to ensure reintegration into the health care and the mental health system.

There is also a clear link between mental illness, homelessness, drug abuse, and incarceration. Many homeless psychiatric patients are arrested for nonviolent crimes including trespassing, petty theft, or possession of illegal substances. About 74% of state prisoners and 76% of local jail inmates who had a mental health problem met criteria for substance dependence or abuse.11 Public policies addressing homelessness and improved care modalities for substance abuse disorders will go a long way towards diminishing incarceration rates of those with mental illness.

Causes of Increased Behavioral Health Treatment in EDs

There are several salient factors contributing to increased behavioral health treatment in EDs including insufficient community resources, a dearth of mental health insurance coverage, and increases in drug use in certain communities. Together, these issues are leading to an influx of behavioral health emergencies visits, growing at a rate 4 times higher than non-behavioral health visits.12

Insurance companies, state and federal government payers, and managed care organizations have reduced reimbursement rates for mental health care, making it difficult for outpatient facilities to operate.13 This lack of funding has led to operational shortfalls for community-based services, causing many outpatient practices to close their doors. For example, a report by the Minnesota Psychiatric Society noted that one organization in the state closed 6 of its 9 outpatient clinics due to inadequate payments.14 As a result, this decline in outpatient and inpatient resources has led to an escalating access crisis, even among those who are insured. More than 50% of U.S. counties do not have practicing behavioral health providers, creating 4,000 designated mental health professional shortage areas.13

Financing mental health services appears to be a major obstacle for those suffering from psychiatric conditions, often secondary to lack of insurance coverage. Despite steady reductions in the number of uninsured Americans under the ACA, there were still 29.3 million Americans lacking health insurance in 2017.15,16 According to a 2009 survey, 61% of those needing but not receiving mental health care listed cost as a barrier.17 Adults with mental illness are much more likely to lack insurance coverage than those without mental illness.18 Moreover, an AHRQ/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) study found that uninsured individuals with behavioral health conditions were more likely to have multiple ED visits during the course of a year, with prolonged lengths of stay in the ED, and were less likely to be admitted to inpatient units.13,19

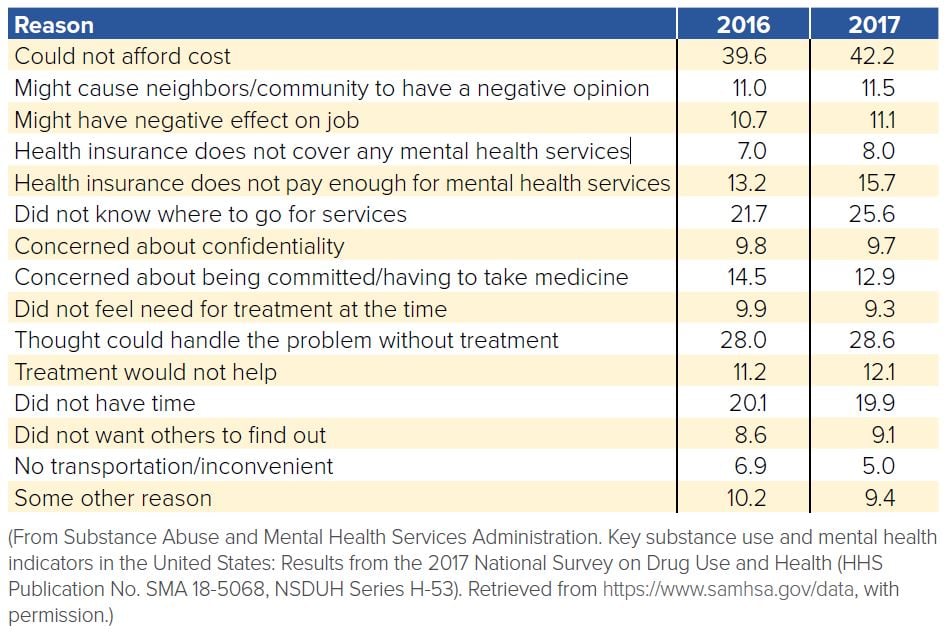

TABLE 24.1. Reasons for Not Receiving Mental Health Services in the Past Year

Among adults aged 18 years or older with any mental illness who did not receive mental health services (in percentages)

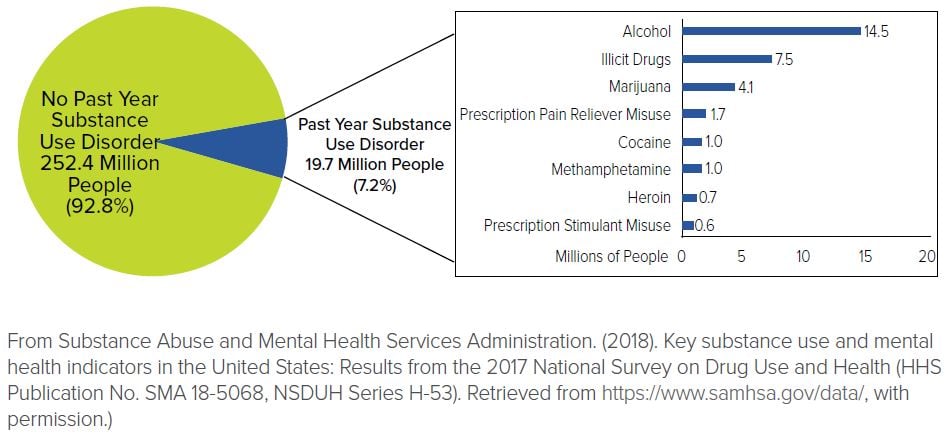

On another front, according to the SAMHSA 2017 report, substance abuse continues to rise, including first-time users of heroin and marijuana (including synthetic marijuana such as Kush, Spice, and K2); the main drivers are marijuana use and the misuse of prescription pain relievers.20 Patients with mental health conditions are not immune from this trend and are seeking treatment for substance abuse and/or intoxication in EDs at an increasing rate. SAMHSA reported 7.9 million Americans have a co-occurring disorder with mental health issue and a substance use disorder as of 2014.21 One study in Maryland reviewing data from 2008 to 2012 showed the prevalence of co-occurring mental illness among substance abuse-related encounters increased from 53% to 57% for ED encounters.22

FIGURE 24.1. Numbers of People Age 12 or Older with a Past Year Substance Use Disorder: 2017

Given the insufficient community resources, lack of mental health insurance coverage, high numbers of uninsured persons in the U.S., shortages of behavioral health providers, and reduced reimbursement rates, it is not surprising that many Americans have unmet behavioral health needs. Increasing rates of substance abuse further compound this problem. This leads to downstream implications that impact treatment in the ED for all patients.

Impact of Increased Behavioral Health Treatment in the ED

Boarding

Psychiatric boarding is one of the most prevalent issues EDs face across the nation. As defined by ACEP, boarding is the holding of patients in the ED after the patient has been admitted to a facility, but not physically transferred to an inpatient unit for definitive care.23

Boarding ties up ED resources including patient beds, care providers, ED staff, and ultimately, health care dollars. It delays the definitive care of psychiatric patients who typically need acute interventions, often exacerbating their conditions and, at times, making it unsafe for these patients and the staff caring for them. Ultimately, psychiatric boarding contributes to ED crowding,24 which can increase wait times, prevent timely evaluation and treatment of those seeking care, increase patient walk-outs, and even increase inpatient mortality.25

A 2015 survey revealed that nearly 70% of emergency physicians boarded psychiatric patients because of the paucity of available inpatient hospital beds or psychiatric evaluation services.26 One group of researchers revealed that the average length of stay in EDs is 42% longer for patients with mental health problems, averaging more than 11 hours nationally.27 In another study, 1 in 12 patients with psychiatric complaints had an ED length of stay of greater than 24 hours.28 A 2012 survey from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors found that 10% of hospitals are boarding patients for several weeks.29

There have been several proposals to help decrease boarding in EDs nationwide; however, more research is needed to validate their impact. First and foremost, access to outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care needs to improve. More state and federal funding should be used to increase access points into the mental health system. Additionally, some states have changed regulations around telemedicine to allow psychiatrists to evaluate and screen boarded patients remotely rather than waiting in overcrowded EDs; additional research

on the role of telemedicine in this setting is underway.30,31 Furthermore, improved psychiatry case management, coupled with outpatient capacity increases, can help reduce acute psychiatric emergencies visits.32

One proposal is to establish benchmarks in ED care of psychiatric patients, such as measuring the number of visits lasting greater than 24 hours.28 This statistic could be used as a quality metric tied to hospital reimbursement rates, incentivizing hospitals to address the problem. Furthermore, concurrent medical and psychiatric evaluation instead of a step-wise evaluation protocol can reduce delays in treating psychiatric patients in the ED.33

Some states have already taken action. For example, Washington State’s Supreme Court issued a ruling banning psychiatric boarding in EDs in 2014, claiming it was a violation of the state’s Involuntary Treatment Act and a deprivation of liberty in violation of the state constitution.29 However, experts point out the decision conflicts with federal law preventing EDs from discharging unstable patients (ie, those who are suicidal or homicidal). Other states, such as New Hampshire, have similar statutory language as in Washington.34 Virginia created an acute psychiatric bed registry, which strengthens the tracking of inpatient psychiatric bed availability via daily updates.35–37

Suboptimal Psychiatric Care and Safety in EDs

Exacerbating the complex problem of boarding, some ED staff may lack adequate understanding of mental illness and resources for safe interventions.13 ED staff often report a sense of fear and anger provoked by psychiatric patients’ aggressive or bizarre behavior.38 Additionally, the “revolving door” nature of many presentations along with poor follow-up care and medication noncompliance results in a sense of hopelessness in some ED staff.38

If ED providers do not receive adequate training in caring for mental health patients,39 they may lack the de-escalation skills and safety techniques that can ensure a safe environment for the patient and themselves. Without these skills, ED staff may prematurely jump to the use of restraints, seclusion, and/or sedatives, which can further deteriorate a patient’s condition or delay definitive evaluation. This can, in turn, increase the length of stay and lead to unnecessary hospital admissions.

It has been postulated that patients who receive higher quality initial care are more likely to go home than stay in the ED as boarders.40 For example, hospitals that participated in the Institute for Behavioral Healthcare Improvement’s 2008 learning collaborative were able to reduce the length-of-stay of psychiatric patients in the ED and the use of seclusion and restraints with low-cost interventions, including improved training for clinical and security staff.40 By providing additional staff training in de-escalation techniques, they were able to significantly reduce boarding times and improve patient experiences.40 Expert policies for de-escalation techniques have been published by groups such as the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry.41

As the number of psychiatric emergencies presenting to EDs will likely not subside anytime soon, it would be prudent to consider increasing psychiatric training for all ED care providers. To promote increased training, funding should be allocated and training programs should be implemented (for example, within residency training and CME frameworks) that target unique features of psychiatric care within emergency medicine.

While proposals have been made at the hospital level and local and state branches of government, there is an immense need to address these problems — boarding of psychiatric patients, ED crowding, psychiatric bed tracking and transfer systems for psychiatric patients — through national legislation. While these local and state efforts are positive steps, more comprehensive legislation is needed to target the numerous problems.

Two examples of ACEP-supported legislation to strengthen behavioral health care in EDs are:

21st Century Cures Act42 (signed into law)

- An amalgamation of multiple mental health reform bills, such as the MentalcHealth Reform Act of 2016 and the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act of 201543,44

- Helped expand the mental health workforce and promote efforts to implement mental health parity in health plans

- Created an Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders and a National Mental Health Policy Lab

- Promoted the use of telemedicine services

- Signed into law on Dec. 13, 2016

The “Excellence in Mental Health and Addiction Treatment Expansion Act” of 2017 (HR 3931/S. 1905)45,46 (introduced in 201747,48)

- Would extend successful pilot programs that do the following:

- Provide much-needed outpatient services for patients with mental or behavioral health needs

- Help transition these patients from inpatient to outpatient status more readily

- Make inpatient psychiatric beds available on a timelier basis for the patients who are waiting for them in the ED

- Would expand available funding beyond the 8 currently participating states to an additional 11 states:

- Helps prevent more patients from reaching a crisis point requiring acute ED services

There are other state, federal, and local bills being actively considered and explored,49 but the fundamental concepts remain the same in all of these legislative efforts: improve outpatient access, reduce regulatory barriers to integrated health, and provide additional resources for mental health treatment. For more information go to https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/mentalhealth.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Advocate for improved resources for comprehensive and preventative outpatient psychiatric care to stem the tide of diminishing acute psychiatric care beds.

- Promote institution-specific solutions that improve the care of the acutely ill psychiatric patient.

- Work with community leaders, health care providers and law enforcement officials to create multidisciplinary initiatives that address the link between mental health disorders, substance abuse and incarceration.