Ch. 8 - Freestanding EDs, Satellite EDs, and Urgent Care Centers

Miles Medina, DO; Melissa Villars, MD, MPH; Thomas J. Sugarman, MD, FACEP

Emergency medical services have expanded beyond the realm of the traditional emergency department that is part of a full-service hospital. As treatment has moved from inpatient to outpatient care, EDs are now separating from hospitals and increasing access in the community, similar to surgery, imaging, and cardiac centers. Freestanding emergency departments (FSEDs) must operate 24/7 to be recognized as EDs, but can be structured in different ways depending on state laws, Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement, location, and ownership. Broadly, they are categorized as:

- Independently owned FSEDs (iFSEDs): Not recognized by CMS nor part of a health system;

- Hospital-satellite EDs (HSEDs): Recognized by CMS and operating under an affiliated hospital’s license, also known as Hospital Outpatient Departments (HOPDs).1

The acute care landscape is rapidly evolving in the U.S. Although there are significant challenges around payment reform, access to care, and EMTALA requirements, the sector also represents potential.

FSEDs are not subject to federal EMTALA regulations, but many are subject to similar state-based regulations and as such, must perform an MSE on all patients regardless of ability to pay.

While not technically FSEDs, other alternatives such as urgent care (UC) centers and private centers such as Kaiser’s multispecialty outpatient clinics called “hubs” are becoming increasingly prevalent and providing acute unscheduled care.

New Delivery Models in Acute Care

Since their advent in the 1970s, studies have demonstrated that these freestanding EDs can provide effective care for a wide variety of emergent conditions.2 Originally created to alleviate the lack of access to care in underserved areas, the growth of both models in non-rural settings has been

supported by changing payment systems that have created new financial incentives.3 Medicare and Medicaid do not recognize iFSEDs as EDs, but they reimburse 24-hour HSEDs as traditional hospital-based EDs. Independent FSEDs have been criticized for locating primarily in highly-insured areas.4-6 The owners of these iFSEDs have countered that they are not able to be profitable in areas with high CMS coverage because they are not allowed to bill CMS for providing emergency care. As payment policy towards FSEDs evolves, the model for success will likely continue to evolve.

The regulatory oversight of iFSEDs is largely determined at the state level, with some states requiring a certificate of need (CON) to operate. This variation can be seen with many iFSEDs in Texas operating without CONs, while in Colorado and Ohio they are required. Certificate of Need Laws generally limit growth of health care infrastructure and as such have been a barrier to the expansion of iFSEDs in many states. The Freestanding Emergency Center Section of ACEP has also emphasized the importance of integrating with the local EMS system to help with disaster response, as demonstrated by the reliance on HSEDs and iFSEDs during and after Hurricane Harvey.

UCs focus on treating lower acuity problems with widely disparate capabilities. Typically, facilities are not open 24/7, do not have diagnostic equipment, do not have advanced imaging beyond plain radiographs, and only have point-of-care lab testing. They may be staffed by physicians or solely by advanced practice providers (APPs). UCs are not subject to EMTALA requirements and are generally incapable of providing emergency lifesaving care. They often rely on the 911 system to transfer higher acuity patients to EDs.

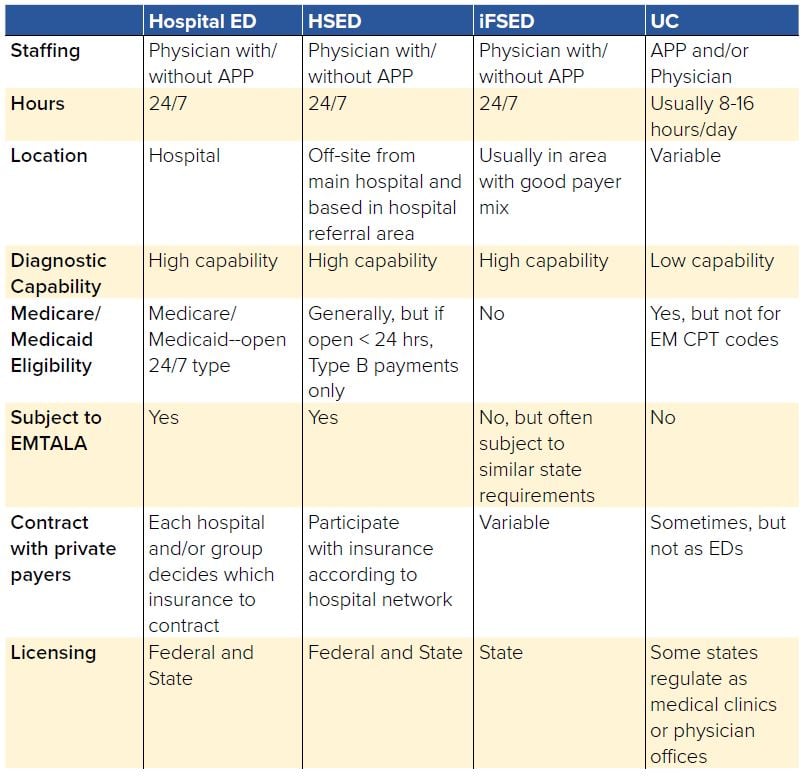

TABLE 8.1. Characteristics of Emergency Care Models

Payment Issues Involving FSEDs

CMS sets federal payment practices and regulations for Medicaid and Medicare. CMS policies determine which services at which locations are reimbursed at emergency rates. Traditional EDs get higher rates because of the overhead required to maintain 24/7 emergency services. In an ED, the reimbursement is divided into two payments, the facility fee and the professional (physician/APP) fee. In contrast, an outpatient doctor’s office visit usually only bills professional fees. UCs are generally treated as offices with no facility charge, although laboratory and imaging tests can be billed separately. Under current regulations, CMS requires that in order to bill as an emergency department, the ED must be attached to a 24/7 inpatient hospital license. This effectively excludes iFSEDs since they are independent of the hospital ownership. CMS treats HSEDs as part of a hospital and reimburses them accordingly with both the facility and professional fee.

Two rates exist for CMS reimbursement for EDs: Type A and Type B. Type A is a rate for facilities that are open 24 hours a day, and Type B is the rate for facilities that are not. It is important to note that Type B rates are approximately 30% lower than Type A, and only about 1% of 2015 ED payments were Type B.7 Total ED rates, Type A or Type B, are significantly higher than urgent care rates for the same billed acuity. However, it is unclear whether the CPT codes adequately capture differences in acuity between UC, FSED, and ED visits.

Rural FSEDs

Rural communities have suffered from fewer health care services and vast travel distances for health care access, resulting in some groups suggesting that FSEDs could fill a needed service void. Because of low admissions, rural hospitals are unable to maintain hospital operating costs, leading to more closures. In 2016, more than 650 rural hospitals, with 38% of critical access hospitals, were at risk of closing because of financial loss.8 The freestanding EDs (both iFSEDs and HSEDs) cost less to operate than a traditional inpatient hospital, but could support a high volume of emergency patients and maintain access to emergency medical care in the community. These freestanding EDs would be able to both risk-stratify and stabilize patients prior to transfer to bigger facilities, should it be necessary. This solution has been considered by MedPAC.7

Though freestanding EDs present a possible solution to the lack of access in rural areas, these areas may not have large enough volumes to generate the needed revenue for an FSED. These economic considerations make rural locations unappetizing for the formation of iFSEDs that cannot receive federal payments. To remedy this, there have been proposals to convert rural hospitals into FSEDs that could receive federal support through traditional critical access funding, subsidies, or enhanced payments. These proposals are very much in their infancy and will require significant changes at both the state and federal level if they are to be successful.

Private Emergency Departments

Many acute patient visits identify health care problems that do not require hospitalization. However, some complaints are far too advanced for a single 20-minute primary care visit. Some highly integrated medical systems have sought to do more advanced diagnostic evaluation without the expense of an ED visit. These systems also seek to serve primarily their insured and thus do not want to open an FSED, which would be open to the public. One large insurer group known as Kaiser Permanente, Mid-Atlantic States (KPMAS) has utilized a “hub” model of care to address this issue. Since 2012, KPMAS has found that 91% of patients treated in EDs could have received adequate care at these specialty hubs — and an estimated 50% of these patients may have been discharged home.9

These hubs are in close proximity to multi-specialty medical offices (physicians may send patients from their offices to the hub), operate 24/7, employ primary care physicians, board-certified emergency physicians, and other specialists, offer ambulatory surgery capabilities, and coordinate direct admission with a partner hospital. The hubs treat Kaiser-insured patients only and are not subject to EMTALA because they are not hospital-affiliated or emergency departments. The hub model demonstrated a 23% decrease in hospital days and ED visits from 2009-2014 and a reduction in the cost of health care delivery of 3–4% compared to the average health care industry growth rate.9 While these hubs operate similarly to freestanding EDs, they fall outside the current regulatory environment for EDs as part of a vertically integrated health system.

Conclusion

The acute care landscape, including UCs, HSEDs, and iFSEDs, is rapidly evolving in the U.S. Although there are significant challenges around payment reform, access to care, and EMTALA requirements, the sector also represents potential.

Advocacy includes:

- Knowing about the presence of freestanding EDs in your state, and the basic state laws and regulations surrounding their operation

- Advocating to protect the safety net provided by emergency departments.

- Supporting innovations that will improve service and access.

With thanks to:

Gillian Schmitz, MD, FACEP

Associate Professor, F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

San Antonio Military Medical Center (SAMMC)

ACEP Board of Directors

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP

Chief Medical Officer, Adeptus Health

Angela Straface, MD, FACEP

Medical Director Denton, Code 3 Emergency Partners

Texas College of Emergency Physicians President, 2008-2009

John Dayton, MD, FACEP

Emergency Physician, US Acute Care Solutions

Emergency Physician/Adjunct Professor, University of Utah

Co-Founder, Utah Chapter, Society of Physician Entrepreneurs

Immediate Past President, Utah College of Emergency Physicians

Chair, ACEP Freestanding Emergency Centers Section