ch. 30 - How A Bill Becomes A Law

Nidal Nagib Choujaa; Tracy Marko, MD, PhD; Melanie Stanzer, DO, MMM

Becoming an effective advocate begins with developing an effective understanding of the legislative process. When “asks” are brought to senators and representatives, it is critical that they are feasible and applicable to the role of the legislative member. Furthermore, learning where a bill stands within the legislative process (the process of becoming a law) will help you tailor a specific ask. The majority of an advocate’s time is spent requesting actions in favor of, or in opposition to, bills that have already been created and introduced to the House and/or Senate. Members of Congress want to hear from their constituents because this is who they represent and ultimately who votes to keep them in office. Advocacy work often starts here. As you progress in your advocacy, you may also meet with other senators or representatives whose roles are more strategic to specific bills, such as members of committees to which a bill is assigned. It is helpful to learn which committees your legislative members serve on to understand their niche within Congress, as well as their familiarity with your bills of interest. This chapter will focus on the U.S. Congress. However, state governments have similar proceedings.

The manner in which a bill becomes law in the United States is a powerful part of the American legislative process and is important for all citizens to understand.

What Is a Bill?

A bill is a proposal introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives and/or Senate that has the potential to become a law if enacted during the 2-year Congress in which it was introduced. Together, the House of Representatives and the Senate form Congress, the legislative branch of the United States government. Every 2 years, the entire House of Representatives is open to election. This is what constitutes the 2-year Congress. In contrast, senators serve a 6-year term, and only one-third of the Senate is up for election every 2 years. Each Congress is further divided into 2 sessions, which run from January to December.

Bills can only be introduced by a member of Congress. However, the bill doesn’t have to be written by the member; it can be authored by any citizen, and increasingly bills are also written by lobbyists.1 If a bill is introduced into the House of Representatives, it will be designated with “H.R.” followed by a number, which is typically in sequence for that 2-year Congress. Similarly, if it is introduced to the Senate, it will have the designation of “S.” followed by a number. In order for a bill to become a law, it must pass both the House and Senate, thus each bill has both a House and Senate form.2 A bill can first be passed through one chamber and then sent to the other. More often, though, a bill is introduced simultaneously to both the House and the Senate, usually with somewhat different language that will eventually need to be reconciled before it can become a law. While they have the same general ideas, there are often specific differences that could be significant, such as mechanisms to generate revenue to support new spending.

A bill may also be referred to by the Congress in which it was introduced and further specified by the first or second year (session). For example, the bill H.R. 836: 114th Congress 1st Session was introduced to the 114th Congress in the 1st session of its 2015–2017 term.

What Is a Resolution?

Another type of legislation similar to a bill is a resolution, which comes in 3 forms: joint, concurrent, and simple resolutions. A joint resolution requires approval by the Senate, House, and president to become a law. The main difference between a resolution and a bill is that joint resolutions are used for continuing or emergency appropriations. Joint resolutions are also used when proposing amendments to the Constitution, in which case approval is required by two-thirds of both Chamber and three-fourths of the states but do not require the president’s signature. Concurrent resolutions are most often used to make or change rules that apply to both houses, as such they require passage in both houses by do not require the president’s signature. The annual congressional budget resolution is a concurrent resolution. As compared to concurrent resolutions, simple resolutions apply to the proceedings of one house of Congress and only require passage through that house.

The Process

With a few exceptions, a bill goes through a similar process in each chamber of Congress.2 However, each bill takes its own course through Congress and may have different rules for debating, amending, and voting. Thousands of bills are introduced each Congress, and only a small percent are voted on and become laws. For example, the 114th Congress ran from January 2015–January 2017 and introduced 12,063 bills and resolutions, of which 661 got a vote (5%), 329 (3%) were enacted into law, and 9 were vetoed by the president without subsequent override by Congress.

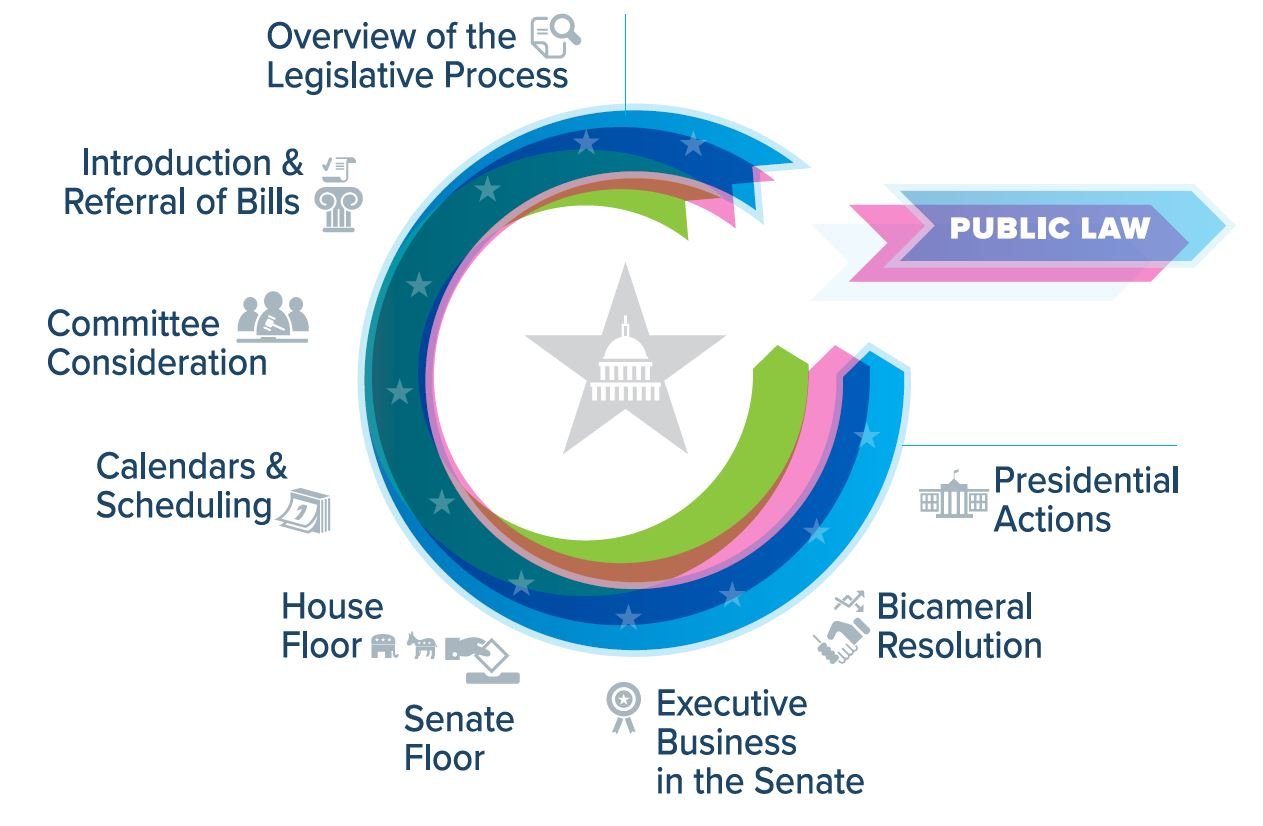

FIGURE 30.1. Legislative Process

Introduction and Referral

As previously noted, any member of Congress may introduce a bill to their respective chamber of Congress. Bills can be first introduced into either chamber with the exception of revenue generation, which must originate in the House, as well as presidential nomination confirmation and treaty approval, which must be given by the Senate. Prior to introducing bills, Congressional members may ask colleagues to co-sponsor their bill to demonstrate broader support.

After introduction, bills are referred to a committee based on the provisions in the bill. Jurisdiction is determined by the chamber’s standing rules and past referral decisions. Committees are comprised of a subgroup of representatives or senators who have been appointed to serve on that committee by their party’s leadership and often remain on the same committees through multiple terms, becoming subject matter experts. Getting to serve on specific committees can be an important career move for members as it gives them added influence, ability to shape legislation, and may serve as a prerequisite for those interested in national campaigns. In the House, bills typically are referred to a single committee. If multiple committees are involved, each will work only on the portion of the bill under its jurisdiction. In the Senate, bills are only introduced to the committee with jurisdiction over the predominating issue.

Examples of House committees include: Ways and Means (jurisdiction over tax-writing and revenue), Appropriations, Budget, and Energy and Commerce (jurisdiction includes the Department of Health and Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration). Examples of Senate committees include: Appropriations, Finance, and Health Education Labor and Pensions (HELP). A number of both Senate and House Committees have subcommittees on health care.

Committee Work and Vote

Committees receive more bills than they can feasibly address each session. The committee chair, who is a member of the majority party, determines the agenda for the committee and what bills or issues the committee will formally hear and modify. The chair’s prerogative in setting the agenda can serve as a partisan roadblock by which many reasonable bills sponsored by the opposing party never progress. Although not required, most bills considered by a committee have a hearing during which committee members and the public hear about the strengths and weaknesses of the bill from other congressional members, industry, and citizens. Committee members will also discuss bills with other members of Congress and staff in settings that are not open to the public. A committee markup is the final step that allows a bill to advance to the floor.

Committee members will discuss changes and vote on amending the bill and whether to send it to the floor for consideration. The markup is also opened to the public for most bills. Committees often have sub-committees, whose role is to hold hearings and produce markups prior to a full committee evaluation. Subcommittee roles and responsibilities vary by committee.

Calendars and Scheduling

After a committee reports a bill to the House or Senate, it is placed on the respective chamber’s calendar. This does not guarantee consideration. The majority party leaders decide which bills the House and Senate will consider, although there are different procedures in each chamber to bring a bill to the floor.

Chamber Proceedings

In the House, most bills follow the “suspension of rules” procedure, which limits debate to 40 minutes and does not allow amendments to be made on the floor. To pass a bill in this way, it must receive a two-thirds vote in its favor. All other bills will be considered under a “special rule” created by the House Rules Committee and adopted by a House vote. The special rule is tailored for each bill and limits the debate time and the number and content of amendments that can be proposed.

The Senate must first vote to bring a bill to the floor for consideration. Unlike the House, there is no time limit to debate or the number of amendments that can be proposed. Senators may speak as long as they wish in an effort to delay and/or prevent a vote from occurring as scheduled, which is called a filibuster. A filibuster can be ended by cloture, which is a three-fifths vote of the Senate to end debate on the bill. One exception to overcoming a filibuster with a simple majority vote is reconciliation. In the recent decades, the use of filibuster and cloture has increased dramatically such that bills in the Senate often require a challenging new norm of a filibuster-proof 60 votes for passage, compared to the simple majority required in the House.

Reconciliation

Reconciliation is another way to avoid Senate filibusters. It can only be used for bills that address the debt limit, spending, and revenues.3 Additionally, it can only be enacted once for each of the above categories during every budget resolution, which is typically once every year. A budget resolution is a concurrent resolution that provides a framework for making budget decisions and sets overall annual spending limits for federal agencies. Although it only requires a majority vote, it is often challenging to pass as it addresses the entire Congress budget.4 Additionally, the Byrd rule only allows topics that are relevant to the bill to be introduced.

Reconciliation has played a major role in health care legislation.4 The Affordable Care Act was passed with a supermajority vote of 60 to overcome a filibuster in 2009.5 In 2010, a reconciliation bill, the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, was passed that made budget changes in the ACA. In 2017, Republicans attempted to start a repeal and replacement effort through reconciliation, which would have significantly changed the budget for the ACA and necessitated a new health care act. Three reconciliation acts were voted on and did not pass the Senate: Better Care Reconciliation Act (43-57), Obamacare Repeal and Reconciliation Act (45-55), and Health Care Freedom Act (49-51).6

Full Chamber Vote

If a bill is passed by the House of Representatives, and there is no corresponding bill in the Senate, then the approved bill is introduced in the Senate and goes through the process again (and vice-versa for bills that originate in the Senate). If there is a corresponding bill approved in the Senate, then a Conference

Committee — made of members from both chambers — will debate and create a joint version of the two corresponding bills to go immediately back to each chamber for a final vote. Regardless of whether one bill is passed through the two chambers, or two separate bills are combined into one by a conference committee, the final bill approved by both chambers will ultimately travel to the president’s desk if passed.

Many bills are “tabled” during committee deliberations and votes, or at a full chamber vote. This means consideration of the bill has been suspended indefinitely, and as a result the bill dies. At any voting point, the bill could also be rejected outright as well. The majority of the 95% of bills that die in Congress meet one of these two ends.

Actions of the President

After the same bill is passed by the House and Senate, it will be sent to the president. Often the president simply signs the bill into law. However, if the president doesn’t sign the approved bill for 10 days, and Congress is still in session, the “Presentment Clause” of the U.S. Constitution mandates that the bill still becomes law. If, however, the Congressional session ends before the 10-day period, the president can use what is called a “pocket veto” by not signing the bill, and it will not become law. Finally, the president has the option to reject the bill outright, an action called a veto, at which point the bill is sent back to Congress. If two-thirds of each chamber votes to re-approve the bill in spite of the president’s opposition, the veto is overridden and the bill becomes law.

Judicial Branch’s Role

The judicial branch can also play an important part in the passage and survival of laws in the U.S. Specifically, the judicial branch is tasked with examining laws that are appealed and determining if they are in line with the U.S. Constitution. This is referred to as judicial review. Interestingly, the Constitution does not explicitly decree the role of the judiciary in the legislative process, as it does with the Congressional and Executive branches. Rather, the power of the courts to declare laws unconstitutional is considered an implied power, based on Article III and Article VI of the Constitution.

For example, two separate challenges to the ACA rose to the Supreme Court for judicial review. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (decided June 28, 2012), the Supreme Court ruled that the individual mandate described in the ACA was constitutional and that states had the right to choose whether or not to expand Medicaid. Subsequently, in King v. Burwell (decided June 25, 2015), the justices ruled that federal subsidies for health care premiums could be used in states that did not have a health care exchange and relied upon the federal exchange. Both of these cases had a significant impact on the ongoing implementation of the ACA.

What Happens After Passage

Before a bill becomes a law, Congress must decide how to fund it, using the current “pay as you go” budgeting rule, also known as “pay-fors.”7 Initially in effect from 1990–2002, and then re-enacted by the 111th Congress and President Obama, this rule requires that each new federal expenditure — such as funding a newly passed law — must be offset by an equivalent reduction in expenses from somewhere else in the federal budget or by legalizing another law that will generate enough revenue, thereby offsetting costs and making it revenueneutral. For example, if a new health care law requires $10 million to enact fully, then $10 million must be cut from other programs or raised through revenuegenerating programs.

Congress uses a process called sequestration to limit budgetary spending.8,9 If the federal budget balance is negative at the end of a Congressional session, the session’s deficit is balanced by deducting from other programs funded by the federal budget. Certain programs are exempt from sequestration, such as those considered to be direct spending. Direct spending is typically composed of “entitlement spending” like Social Security, Medicaid, all programs under the Department of Veterans Affairs, net interest on the debt, and income tax credits, among others. Medicare is not exempt; however, it is limited to a 4% reduction. This can magnify the impact of cuts on the parts of the budget deemed discretionary.

Finally, if offsetting cuts to programs or additional revenue cannot be found to fund the programs or laws that are passed, then the new law or aspects of the law may be underfunded or not funded at all.10 For example, in the ACA there was a provision for a study on workforce shortages that has not yet been funded, despite its inclusion in the law. Regardless of the pathway chosen, limits on funding are a final mechanism to prevent a law from being fully enacted.

Conclusion

The manner in which a bill becomes law in the United States is a powerful part of the American legislative process. It is important for all of us to understand as citizens, and especially critical for us to know as health care providers, in order to effectively advocate on behalf of our patients and our profession.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Use your understanding of how a bill becomes a law to engage and participate in advocacy efforts at appropriate times in the process.

- Understand what makes a good “ask.” For example, requesting your representative or senator to co-sponsor, suggest an amendment to, or vote in favor of, or in opposition to, a bill being considered on the floor.

- Learn on which committees your legislative members serve to understand their niche and role within Congress as well as their familiarity with your bills of interest. This will enable you to appropriately tailor the background information you provide and guide your discussion.