Ch. 31 - Legislative Advocacy

Michael S. Balkin, MD; Nicholas Robbins, MD; Heidi Knowles, MD, FACEP

Throughout their careers, emergency physicians will encounter patients suffering the medical consequences of broader social and political issues. Political advocacy offers the opportunity to effect societal change that will improve the conditions for patients and physicians alike. One of the many ways to advocate is to engage with legislators directly. The following sections provide a framework for becoming engaged with legislators at all levels of government as an emergency medicine advocate.1-3

Advocacy can take many forms — but in every case, it’s important to know your lawmakers, be familiar with the legislative process, and become effective in communicating with the parties who influence that process.

Identify Your Specific Passion: Why You Advocate

According to the ACEP Code of Ethics for Emergency Physicians, emergency physicians have an ethical duty to promote population health through advocacy and to participate in “efforts to educate others about the potential of welldesigned laws, programs, and policies to improve the overall health and safety of the public.”4 Physician advocacy can range from working toward state health care reform to advising a local school board.3 Advocacy activities might include attending a physicians’ day at the state capitol, testifying before a committee, or corresponding and meeting one-on-one with an elected official.5

Regardless of the advocacy venue, it is crucial to identify a personal topic that nourishes your passion for advocacy. It may seem unlikely that a letter or conversation from an individual physician could impact public policy, but multiple cases demonstrate that passionate physicians can, indeed, affect legislation.

Consider these examples:

- • ACEP members urged several U.S. legislators to support bills aimed at curbing opioid use in 2018;6 H.R. 6 was subsequently signed into law that provides grants to support treatment for emergency patients with substance-use disorders and includes many provisions aimed at preventing opioid addictions.

- In 2018, a key federal advisory committee voted to recommend an ACEPdeveloped Alternative Payment Model to HHS Secretary Alex Azar for full implementation; the model joins only 4 others to receive such a vote (out of 26 proposed).7

- After ACEP joined other specialties in directly beseeching the FDA to solve the continuing problem of drug shortages, the agency announced a new focus on mitigating critical drug shortages — with the help of the house of medicine.8

- During the debate about patient dumping, before EMTALA became law, Dr. Arthur Kellermann famously dumped hundreds of patient wristbands onto the table to illustrate the human toll of patient dumping — creating a pivotal point in the debate.9,10

Be Informed

Research your topic thoroughly and know your subject matter. Also understand your opponents’ arguments, which will enable you to address criticisms in advance. For federal or national EM issues, begin by visiting www.acepadvocacy.org to research existing issues, policy briefs, and legislative updates. Another way to stay abreast of the most recent updates on EM-specific legislative issues is to sign up for the ACEP 911 Grassroots network. For other health care issues, consider using non-partisan think tanks to acquire supportive detailed information, such as the Commonwealth Fund, Kaiser Family Foundation, and recently publicly available Congressional Research Service reports. Additionally, be familiar with current legislation on your topic and understand your legislator’s perspective. Note any news articles, non-academic literature, and relevant academic publications either supporting or opposing your position on the issue.

Understanding multiple sides of an issue strengthens your position when speaking to a legislator or his/her staff and strengthens the legislator’s ability to discuss their position. If you are dealing with a state or local lawmaker, research when and how other states or local communities have addressed similar issues. Before contacting any lawmaker, know which committees they serve on, research their voting record, and understand their constituencies so you can make an effective advocacy pitch. Websites of elected officials contain extensive information about the personal and professional background of legislators. Attending the annual ACEP Leadership & Advocacy Conference in Washington, D.C., and attending state legislative events can advance your advocacy experience. If your state ACEP chapter does not organize a lobby day, your state medical society may host one that you could join, or you can contact the EMRA Health Policy Committee for tools on how to conduct your own.

Advocacy Through Organizations

While it is crucial to demonstrate a detailed understanding of your issue, remember you are already well-positioned to make an impact. Your role as a physician gives you a great deal of clout; physicians enjoy considerable social status and respect as healers, scholars, and public servants. A survey of legislative assistants reported that 90% of physician lobbyists were either very effective or somewhat effective — and, in the words of one legislative assistant, “should recognize the power they have to influence Congress.”11 Moreover, within the current health care system, emergency physicians provide a disproportionate share of the care for the underinsured — far more than any other medical specialists.12 This further sets our specialty apart and gives us a more powerful

voice in the public policy debate.

Partnering with supportive organizations such as EMRA, ACEP, AMA, or a local grassroots network can add the legitimacy of a trusted source and weight of popular opinion to your issue, making legislators more likely to respond and act. Additionally, these professional organizations may have already laid the groundwork to present your issue; their government affairs staff may have established relationships with legislators and may be able to help refine and

tailor your arguments.13 They can offer contacts to like-minded interest groups

and lobbyists. Inviting stakeholder groups to participate in your effort can earn

valuable allies, bolster support, and facilitate passage of a bill. Just as modern

medical paradigms incorporate a health care team with a physician as team

leader, various members of a lobbying team bring diverse knowledge and skills

to the table, resulting in more effective advocacy.14

Advocacy Through Writing

Share your efforts with the academic and public policy community. Legislative officials and their staff read and watch various sources of media (including editorials, television, government reports, and academic publications) to keep up with the issues that matter to their constituents. Letters to the editor (LTEs) represent a popular method of advocacy that can highlight topics and shape policy debates. Many influential LTEs are published in major medical journals, such as the Journal of American Medical Association, the Lancet, the Annals of Emergency Medicine, as well as their supplemental online counterparts (blogs, Web articles, etc.). LTEs or op-eds in a wide array of outlets may gain even more attention with legislative staff. Op-eds may be difficult to get published via national outlets, but an important and more accessible audience is local newspapers, which are often interested in running local physician opinion pieces. Recently, some organizations have recognized the untapped power of underrepresented writers, and groups such as “The Op-Ed Project” have sprung up to mobilize potential writers into action.

Scholarly publications on advocacy remain relatively scarce. Advocacy often does not fit in the traditional scholarship model and typically has not been rewarded with promotion or tenure. Opponents of increased calls for advocacy in the medical profession even argue that advocacy may subvert academic scholarship. Models for scholarly advocacy do exist, however. Influential American educator Ernest Boyer, PhD, proposed an alternative model in which advocacy may be considered the “scholarship of application” alongside the more traditional scholarship of discovery.

Core Advocacy: Direct Communication & Relationship with Elected Officials

The first step is to establish contact with your elected official or his/her office. Reach out to staff who are responsible for the daily office activities. Utilize local, state, and federal websites to get names and contact information.

Snail Mail

While traditional mail largely has been supplanted by electronic communication, hard-copy letters remain effective in advocacy. A tangible letter makes a bigger impact than an email and demonstrates that you did more than just cut and paste. Use a standard format; a single page should be sufficient, summarizing 1-2 key issues in language any educated layperson can understand.13 The following is one example:

Sample letter

500 West Way

Indianapolis, IN 40000

January 1, 2013

The Honorable P. Smith

Indiana Senate

Indianapolis, IN 40000

Dear Sen. Smith,

I am a constituent of yours from Franklin County, writing to ask for your support of the proposed bicycle helmet law (Senate Bill 400). As an emergency medicine physician, I see many children present to the emergency department with head injuries that could have been prevented by wearing a bicycle helmet. The story of Billy K., also from Franklin County, stands out in my mind. He is a 5-year-old who was just learning to ride his bike. No one on his street or in his family had ever worn a bicycle helmet; they were not even aware it was a safety concern.

When Billy arrived to the emergency department, he was confused and had a large cut overlying a skull fracture to the back of his head. After a week in the hospital Billy went home, but had he worn a helmet, he might not have been injured at all. Fortunately, he was able to return to normal activities, but not all children are so lucky. Approximately 7% of all brain injuries are related to bicycle accidents;15 one study shows that the use of bicycle helmets can reduce the risk of head injury by 74% to 85%.16 Finally, the CDC recommends that states increase helmet use by implementing legislation, education, and enforcement.

If you have any questions about my personal experience or the research regarding bicycle helmet safety, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Thank you for considering supporting Senate Bill 400.

[Handwritten Signature]

Jane W. Doe, MD

The ease and speed of email have made it a convenient way for the public to contact legislators; however, this ease and convenience can discredit its content. While form emails may be the most common type of email engagement, they are one of the least influential.17 Your email must demonstrate the same interest and passion as any other communication. The subject line should state you are a constituent.18 Draft your email as you would a letter: include an introduction,

specific request, reasoning for your request, proposed impact of request, personal story on how constituents are affected by issues, and a thank-you.

Telephone

Taking the time to call a legislative office — in Washington, D.C., in state, or locally — can be productive and efficient, even when you speak with a staff assistant rather than your elected official. (Legislative assistants often weigh in on votes and as such have substantial influence over policy decisions. Be respectful and courteous; you may gain an ally and knowledgeable resource.) Identify yourself as a constituent, name the bill or legislative issue at hand, and be brief about your support or opposition. Telephone calls can be ideal when a bill is up for vote. Many legislative offices use specific software to log contacts and keep a tally of how many constituents are interested in an issue.

Social Media

Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and other social media sites are avenues to advocate for important issues. One poll of House and Senate offices showed that anywhere between 1–30 comments is sufficient to garner the attention of senior staff.19 Unique comments or tweets on a subject over multiple days may be more effective than those with repeated language copied from multiple users.

In general:

- Retweet and comment on posts from your legislator’s office.

- Build followers who support your issues.

- Show your engagement on issues with posts and pictures.

- Demonstrate your knowledge on issues over time.

- Remember that every post may be read by an elected official or the general public.20

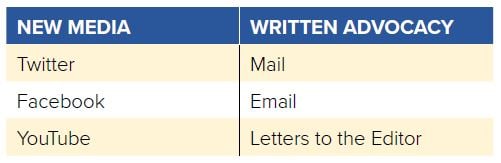

TABLE 31.1. Evolving Channels of Influence

Face to Face

Taking the time and trouble to visit a legislator’s office in person makes an impact. Contact the office scheduler to set up individual meetings, making sure to identify yourself as a constituent.

When you have your appointment set, it’s time to prepare. If you don’t know your legislator, read up — find out what issues are important to him/her, get an idea of his/her voting record, and even check to see if you have anything in common (Same alma mater? Hometown? Drawing personal connections can sometimes make you — and your position — more memorable.) If you plan to discuss current legislation, research where the bill is in the legislative process, who the other co-sponsors are, if the bill has previously been introduced, and what proponents and opponents are saying about it. Be ready to address these key points.

On the day of the meeting, dress professionally, arrive early, and wait patiently. Whether you meet your legislator or a staff member, introduce yourself, shake hands, state where you are from, if you are a constituent, and if you represent a group, yourself, or both. Then, clearly explain what you want from the legislator (ie, sponsorship or support of a bill, co-signing a letter). Tell your story, give a few pertinent facts, repeat your request, and entertain questions. But remember you are talking to real people. Be flexible and hold a normal, relaxed, and open conversation. Maintain a pleasant, professional tone — even if you sense opposition. Do not become derogatory or defensive. Try to frame your position in positive terms and portray yourself as in support of an issue rather than against an opposing view, which may invite critical, unfavorable questioning by the staff or legislator.13

Be respectful of your legislator’s time, thank him/her at the close of the conversation, and indicate you will follow up on your request. Leave behind a “one-pager” explaining the issue and the position you would like the legislator to take. Include your contact information and availability for further conversation. After the meeting, send a thank-you note and any additional information the office may have requested. Don’t forget this step! Follow-through (or lack thereof) speaks to your level of engagement in the issue.

When to Make Contact

There are a variety of strategies for timing when to meet your legislator. Make contact when a bill of interest is coming up for a vote in committee or on the floor or if you have new bill language that has been drafted. Additionally, Congressional recesses are opportune times to meet locally with your legislator because the office will be less busy; these dates can be obtained from the local/ district office. You can also invite your legislator to tour your ED for a firsthand look at issues specific to your facility, as suggested by ACEP.

Proposing a Bill

If you have scheduled a meeting to ask your lawmaker to sponsor a new bill, do your homework first. It’s important to find a legislative champion for your cause, but you’ll likely need multiple lawmakers to sign on. If appropriate, offer to reach out to legislators who might serve as a key sponsor, a co-sponsor, or a supporting sponsor. When a bill is in committee, offer testimony on the record.21 Contact your legislators again when legislation is coming to a vote; after a vote, thank them (regardless of the outcome). Maintaining contact, like building any relationship, requires effort and persistence, but it can lead to support on future projects.

Testifying Before Committee

Testifying before a legislative committee is more structured than individual meetings and is guided by the committee chair. Many who testify will have prepared remarks; at the least, bring talking points and salient facts to which you can refer.

For your testimony, start by introducing yourself, explaining your credentials, and stating whether you support or oppose the bill in question; then, make your case and be prepared to answer questions. You are there as an expert and have the ability to sway minds, so come prepared and show evidence

or examples to support your case. An example of compelling testimony was Dr. Arthur Kellerman’s testimony against patient dumping before the House Intergovernmental Affairs Committee.9 He collected more than 300 wristbands of indigent patients who were transferred in unstable condition to the public hospital where he worked because of their inability to pay at the private hospital where they initially were seen. In delivering his testimony, he dumped a trash bag full of these wristbands onto the table, stunning the audience and making the issue immediately tangible. This is often cited as one of the critical events that contributed to the passage of EMTALA.

Conclusion

Emergency physicians are ideally situated to advocate for the health of both individual patients and communities as a whole. Advocacy can take many forms – but in every case, it’s important to know your lawmakers, be familiar with the legislative process, and become effective in communicating with the parties who influence that process. Find your passion and use the information and strategies in this handbook to speak up for your specialty, whether on a local or national scale. Be patient, be persistent, and continue to serve as your patients’ voice.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Identify your specific passion and why you choose to advocate.

- Advocacy through leadership is central; focus on coalition-building.

- Utilize all available contact options when advocating for your position.

- Write letters to the editor and op-eds that utilize personal stories and data to advocate for your issues.

- Develop relationships with your legislative offices by creating lines of communication, while employing trusted information and reliable opinions.