Ch. 27 - Drug Shortages and Prescription Drug Costs

Udit Jain, MD; Sushant Kapoor, DO, MS; Peter S. Kim, MD; Teresa Proietti, DO

On June 12, 2018, the AMA declared drug shortages to be an urgent public health crisis.1 Although drug shortages have become more apparent in recent times, the problem has been prevalent for over a decade. In 2005, the FDA’s Drug Shortage Program reported 61 national drug shortages; by 2011, this number increased four-fold.2 A similar trend was seen in the University of Utah’s comprehensive drug database, with a three-fold increase in drug shortages from 2001 to 2014.3

Drug shortages have been increasing in frequency while drug costs have been rising. Both of these issues must be addressed to protect patients and our safe practice as emergency physicians.

In late 2017, Hurricane Maria damaged the main drug manufacturing infrastructure, significantly reducing the supply of saline bags.4 The inability to compound hundreds of drugs exacerbated an already prevalent drug shortage problem, leading to a crisis. As of late 2018, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists listed 188 drug shortages, approximately 40% of which are medications used in the ED for resuscitation, rapid sequence intubation, and the treatment of seizure, sepsis, and acute pain.5

Emergency physicians rely on injectable drugs to diagnose and manage acute illnesses. In our rapid-paced and demanding environment, we recognize the negative impact of drug shortages on patient outcomes and the physicianpatient relationship. Finding effective alternatives to standard medications is both challenging and costly. ED providers are well versed in the most commonly used drug names, doses, and side effects used for patients in extremis.2,3 Limited experience with alternative agents in high-acuity conditions may lead to medication errors and delays in care, ultimately affecting patient safety.2,3 The added pressure on hospital pharmacists to identify alternatives, track inventory, and determine how to best ration the limited supply, represents costly and timeconsuming endeavors.2,6

In addition, informing patients they cannot receive necessary, standard-of-care medication inevitably damages the physician-patient relationship.6

The etiology of the drug shortage problem is multifactorial. There is interplay between quality control and pharmaceutical manufacturing issues, as well as current federal policies.2-4

Quality Control and Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

The landscape of pharmaceutical manufacturing has changed in recent years. In 2015, Pfizer acquired Hospira, the world’s leading provider of generic sterile injectable drugs.7 Prior to and following the acquisition, poor quality control, faulty manufacturing equipment, and contamination issues have caused significant delays in generic drug development.7 Another problem is difficulty in obtaining raw materials.7 This is best demonstrated in the case of intravenous opiates, 75% of which are produced by Pfizer.7 The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) strictly allocates the core ingredient to manufacturers based on previous sales.7 Preventing access to raw materials to the already small number of generic drug manufacturers further exacerbates the drug shortage problem. Petitions to the DEA from various medical societies has improved the allotment process; however, there are still many problems with the process.7 Finally, the cost associated with producing generic injectable drugs is higher than the profit margin, limiting incentive for production.2,4,7

Federal Policy

In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) andated that pharmaceutical manufacturers report drug shortages to the FDA at least 6 months in advance.3,4 The intent was that this process would allow the FDA to work with manufacturers to resolve production issues, identify alternative manufacturers, and expedite inspections and the review process.3 Although this law decreased the number of all new acute drug shortages, it did little to decrease the total number of active acute care drug shortages.3 The FDASIA does not:4

- Obligate manufacturers to disclose the specific problem that caused the interruption

- Obligate manufacturers to provide timeline for resolution

- Require the manufacturer to continue making the drug

- Penalize the manufacturer for not reporting the drug shortage

- Require manufacturers to establish contingency planning

The FDA has also tried to mitigate drug shortages under Section 503B, which allows certain pharmacies to compound drugs in short-supply without a prescription.4 However, the unpredictability of drug shortages and their duration prevents quick mobilization of these outsourced pharmacies to replenish drug supplies.4

There is currently no policy to address the impact of mergers on drug supplies, as in the case of Pfizer and Hospira.4

Almost all hospitals belong to a Group Purchasing Organization (GPO), which leverages the purchasing power of multiple providers to negotiate a better contract with pharmaceutical suppliers.8,9 When the Medicare Anti-Kickback Safe Harbor Statute was passed in 1987, it pardoned GPOs from being criminally prosecuted for taking payments, in the form of administrative fees, from the pharmaceutical suppliers.8,9 This creates a conflict of interest because it changes the original role of the GPOs, which was to reduce drug costs, to becoming a representative of the pharmaceutical companies.9 This could drive down profit margins for the manufacturers, further limiting incentive for generic medication production and some feel that GPOs may be a significant contributor to our current drug shortage crisis.8

The Economics of Drug Manufacturing

The prices of 14 common medications were increased by 20% to 85% between 2008 and 2015, according to a 2017 Government Accountability Office report.10 This pricing increase is not clearly explained by pharmaceutical companies and puts lifesaving treatments, such as insulin, out of reach for patients who rely on them. When patients are not able to access crucial treatments because of high costs, this worsens their health and indirectly causes health care costs to rise.11

In some cases, patients who cannot afford their regular medications may arrive at the ED at more advanced stages of disease.12 Consider the national increase in injectable epinephrine prices that caught national attention in 2016. The price for the commonly prescribed 2-pack of auto-injectors went from $100 in 2009 to $600 in 2016. Many patients may require yearly renewals for this medication, which is single-use and must be readily available at home, school, and work.13 Without this time-sensitive drug readily available, patients cannot treat their symptoms of anaphylaxis early, and their chance of ending up in the ED with a life-threatening allergic reaction increases.

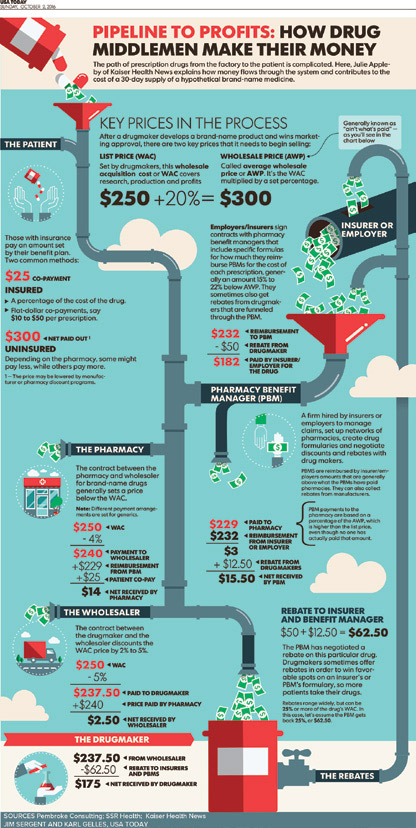

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) serve as the middleman and strike deals between drug makers and health insurers. They create formularies and make coverage decisions. PBMs negotiate rebates from drug manufacturers to insurers in exchange for better coverage terms for insured patients — often in the form of lower co-pays for brand name drugs. But the system has come under scrutiny for the lack of transparency and for the burden it places on consumers. Policyholders’ co-pays and other out-of-pocket costs are typically based on the list price of the drug, not the cost after the rebate, so only insurers, and not patients, benefit from the discounts generated by the rebates.14-16

FIGURE 27.1. Infographic17

Medicare and Medicaid cover 1 out of every 3 Americans, yet they are not allowed to negotiate prices on prescription drugs.11 Medicaid currently operates under the “best price” rule. This rule requires drug manufacturers to offer state Medicaid programs the “best price” they provide to any other purchaser, plus a rebate of 23.1% off that price, and in return, the Medicaid program will cover all of that manufacturer’s drugs.18 Drug manufacturers must participate in this program or risk exclusion from all federal programs (including Medicare). Critics argue this program is failing to help keep drug costs down because it inhibits the ability of private insurers to negotiate with drug manufacturers and inhibits the ability of Medicaid programs to use a formulary to keep costs down, as all drugs made by manufacturers must be covered under this program.18 The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), which established Medicare Part D, included a ban on the ability for CMS to negotiate directly with drug companies to set prescription drug prices.19

The Trump administration considered value-based pricing as a solution to high drug costs. This pricing model bases the cost on the product’s benefit to the customer, instead of on the cost of developing the product. In the context of medications, it is unclear whether it will truly achieve savings for the patient. Instead, highly effective drugs could be incredibly expensive — meaning the drugs that may be the most beneficial to patients could be the least affordable.19-20

Physician Advocacy on Pharmaceutical Costs

The AMA has made efforts to improve patient access, lower costs, and reduce administrative burdens without stifling innovation. The AMA has opposed provisions in pharmacies’ contracts with PBMs that prohibit pharmacists from disclosing that a patient’s co-pay is higher than the drug’s cash price, and has advocated for policies that prohibit price gouging on prescription medications.21 There is also a push for price transparency via a grassroots campaign, TruthinRx.com,11 a website created to hear directly from patients and physicians about their struggles to afford medications.

Physician Advocacy on Drug Shortages

To address the issue of worsening acute care drug shortages, ACEP successfully lobbied Congress to ask the FDA to establish an “interagency, interdepartmental, and multidisciplinary task force to determine the root causes of drug shortages and develop recommendations to Congress to ensure patient access to vital emergency care.” In May 2018, ACEP developed a letter to FDA calling for changes; this letter had bipartisan support from members of congress and led directly to action by the FDA.22,23 The FDA Drug Shortages Task Force aims to assess the adverse consequences of drug shortages on patients and health care providers, and then identify the root causes and drivers of drug shortages so that strategies for preventing or mitigating drug shortages can be identified and enacted.22-24

Summary

Over the past few years, drug shortages have been increasing in frequency while drug costs have been rising. HHS and the Department of Homeland Security have been urged by multiple medical societies to view the drug shortage crisis as a national security initiative.1 High drug costs have drawn increasing media attention as patient’s lives are put at risk when they cannot afford necessary medications. Both of these issues must be addressed by policy change to protect patients and our safe practice as emergency physicians.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Share your stories to highlight the challenges and harm active drug shortages and high drug costs pose for our patients.

- Advocate for revisions to the current policies and regulations to mitigate the problems of high drug costs and drug shortages.