Ch. 9 - Introduction to Payment

Justin Fuehrer, DO, FAWM; Jordan Celeste, MD, FACEP; David A. McKenzie, CAE

Physician reimbursement can be an overwhelming and confusing topic for physicians. This chapter focuses on some of the basic information regarding how emergency medicine physicians are reimbursed, what documentation must be completed to be reimbursed, as well as information regarding relatively new changes to reimbursement as a whole. Historically, physician reimbursement has been based on quantifiable metrics such as the number of patients seen and procedures performed. The health care landscape is experiencing a shift in payment models, with insurers tying reimbursement to quality measures and value-based purchasing.

The health care landscape is experiencing a shift in payment models, with insurers tying reimbursement to quality measures and value-based purchasing.

The Traditional Payment Process

The core of physician reimbursement is based on documentation, the codes generated from that documentation, and RVUs (Relative Value Units) attached to the visit type; these factors ultimately determine the reimbursement amount. Professional coders sift through the physician’s chart, and based only on the documentation provided, assign specific codes used by payers to determine reimbursement. The coders use the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code set to bill for the services and procedures provided to a patient. CPT is created and updated by the American Medical Association CPT Editorial Panel and CPT Advisory Committee, which is composed of a member from each specialty society. The CPT Editorial Panel also includes CMS and other representatives from the payer community, such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield, America’s Health Insurance Plans, American Hospital Association.1 The CPT code set includes codes for evaluation and management, critical care, observation services, and specific procedures.2,3 These codes form the basis for reimbursement, with some payers having additional modifiers and criteria attached to their final payment amount.

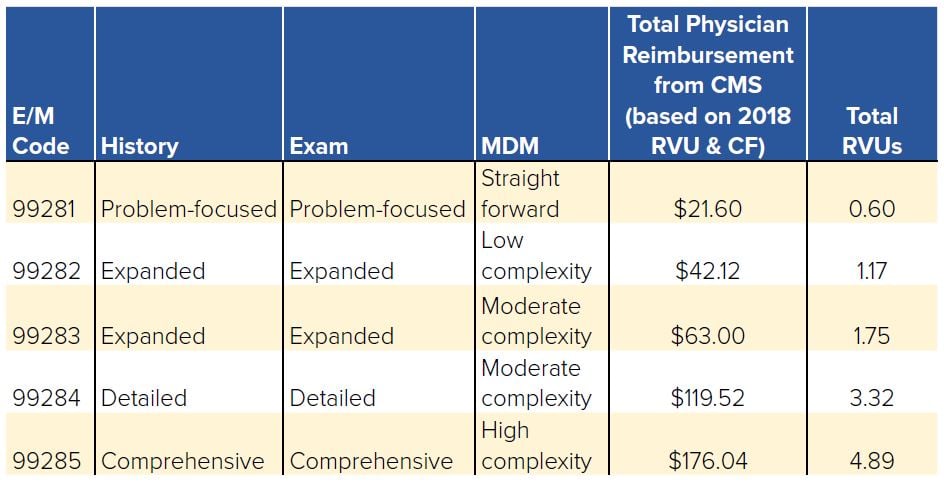

Evaluation and Management (E/M) codes describe the cognitive work that is involved in taking care of a patient. These are derived directly from a patient’s chart and based on numerous factors, including: history, physical exam, complexity of medical decision-making (MDM), counseling, coordination of care, nature of presenting problem, and time. However, CPT specifically states that time is not a descriptive component in selecting ED E/M codes, because of the variable intensity and frequent need for multiple encounters over an extended period of time in that setting. History, physical exam, and MDM are the key components that determine the appropriate E/M code, with the MDM illustrating to the coders the complexity of the patient encounter.4 There is a relatively small number of E/M codes used in the ED, and the most commonly used are codes 99281-99285 (sometimes referred to as level 1 through level 5 charts) with the higher numbers representing more complex patient care and subsequently higher reimbursement, and codes 99291-99292, which are used for critical care billing.5 The criteria and extent of service needed to generate certain E/M codes is outlined in Table 9.1 and the corresponding Medicare payment rates. It is important to note that the critical care codes 99291 and 99292 are not used as often as might be applicable in the ED, potentially leading to lost revenue.6

TABLE 9.1. Understanding E/M Codes

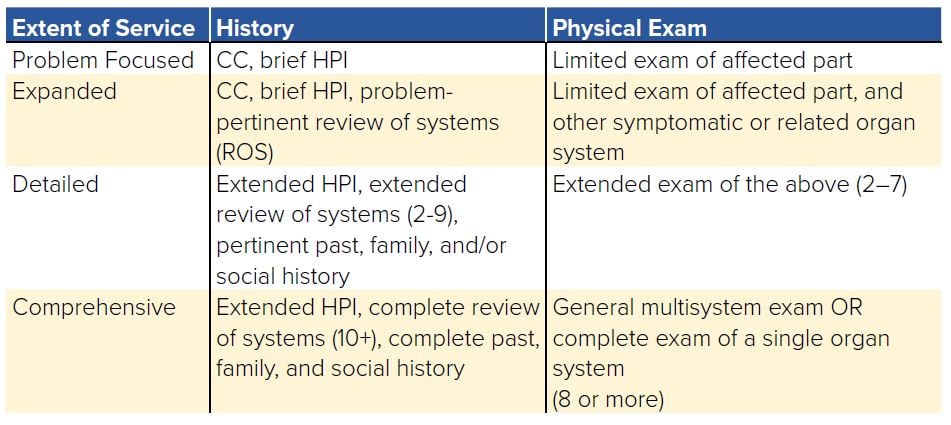

For E/M Codes 99281-99285, certain criteria must be met with regard to documentation in the history and physical exam sections. As can be seen in Table 9.1, this information can range from problem-focused to comprehensive. Table 9.2 describes the specific documentation criteria required to meet the extent of service requirements.3 For example, a 99281 code would require only a chief complaint (CC), brief HPI, and limited exam of the affected part to qualify.

TABLE 9.2. Meeting Extent of Service Requirements

The last section of documentation, the MDM also has specific requirements ranging from straightforward to high complexity, as can be seen in Table 9.1. MDM complexity is determined by 3 components:

- The number of diagnoses and management options considered

- Data and testing reviewed

- Potential risk of complications, morbidity, and mortality to the patient

For example, straightforward complexity criteria include minimal number of diagnosis and management options considered, minimal or no data reviewed, and minimal risk of complications, while high-complexity criteria include an extensive number of diagnosis and management options considered, extensive amount of data to be reviewed, and high risk of complications.3

These CPT codes generated by physician services are assigned an RVU that ultimately determines the reimbursement rate. RVUs are allocated by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), which is also composed of representatives from each of the 25 medical specialties and an additional 6 assigned representative seats. The RUC uses the Resource Based Relative Value Scale to determine the RVUs assigned for each specific service and is responsible for making recommendations on the value of these codes to CMS.

CMS ultimately decides the RVUs assigned to each CPT code, but generally follows advice from the RUC.

Assignment of RVUs must be done in a budget-neutral manner, as there is a finite amount of federal money assigned to physician reimbursement. This means increasing the RVU for one specialty/procedure may result in a decrease in the RVU for another specialty/procedure, ultimately affecting their respective reimbursement.

The RVU is assigned based on 3 components:

- The value of physician work (WORK)

- The value of practice expense (PE)

- The cost of malpractice insurance (MP) or Professional Liability Insurance (PLI)

These 3 components ultimately make up the RVU formula with adjustment based on geographic location, the geographic practice cost index (GPCI), and a conversion factor (CF):

- (Work RVU x Work GPCI) + (PE RVU x PE GPCI) + (MP RVU x MP GPCI) = Total RVU

- Payment = Total RVU x CF

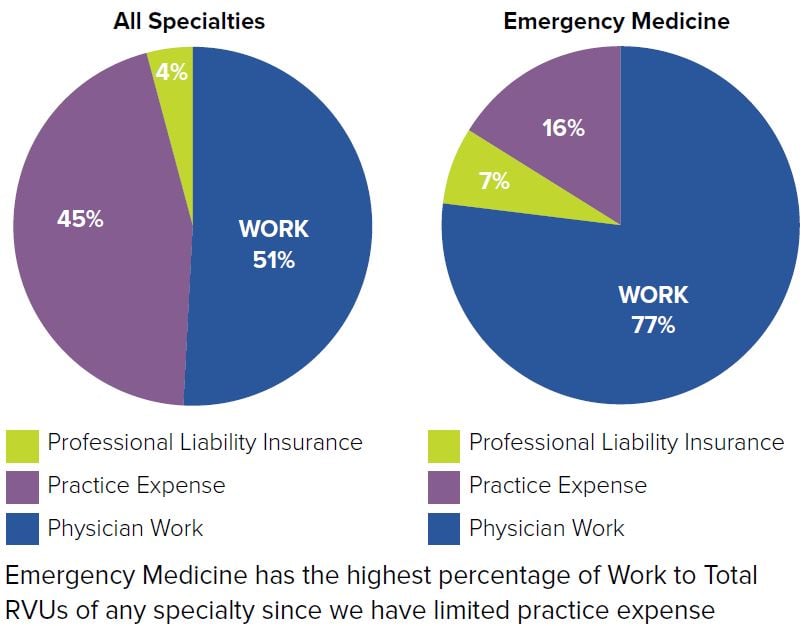

The physician work component accounts for about 51% of the total RVU for each service overall, but is closer to 77% for ED E/M codes. Work is determined based on the intensity over the time it takes to perform the service, as measured by the skill and physical effort, mental effort and judgment, and stress because of the potential risk to the patient. The PE component accounts for an additional 45% on average, with the PLI accounting for 4%.6 The PE component will be less of an RVU factor for hospital-based specialties, such as emergency medicine, given lack of operating expenses as compared to private outpatient facilities.

FIGURE 9.1. Work to Total RVUs

The GPCI adjusts for cost differences in all 3 areas of the total RVU formula — physician work, practice expense, and cost of malpractice insurance. For example, the GPCI component of practice expense takes into account the cost of rent between 2 different cities and would apply a higher modifying factor to the more expensive location. An area of the country with an exceptionally costly malpractice environment would also receive a higher modifying GPCI factor for the MP component. Physician work has been a topic of debate because it is determined based on the specific encounter or procedure itself and is not necessarily influenced by geographical factors. The GPCI factor for physician work is determined based on differences in compensation for similar professions.7 This final RVU is then multiplied by a conversion factor (CF), which is set each year by CMS and ultimately determines the dollar amount in payment received. The CF for 2018 was set at $35.9996.8

This can be demonstrated using the example of drainage of a simple abscess (CPT code 10060) in disparate parts of the country.9 This results in the reimbursement for a simple abscess drainage in Fargo, ND, being $97.19 versus $118.07 in Queens, NY.

Historical Medicare Reimbursement

Medicare has historically reimbursed physicians by a fee-for-service model. This type of model focused on volume, patient visits, and procedures. Currently both CMS and private insurers are shifting toward a reimbursement model that rewards physicians for providing value, delivering quality, and utilizing resources effectively.

A huge component of the previous Medicare reimbursement system was Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR). Initially, the SGR was passed into law in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 as a way of controlling rising medical costs by linking reimbursement rates to the gross domestic product (GDP). The goal was to ensure the annual increase in expense per Medicare beneficiary did not exceed growth in the economy as measured by per-capita GDP.11,12 However, tying reimbursement to the GDP failed to account for the actual cost of health care expenses because it did not consider the rising costs of medical technology, increased utilization, or increasing complexity of patients. The linkage also did not account for the traditional economic cycles that involve recessions (eg, 2000 tech bubble) that would result in a decline in payment. These challenges made the SGR fatally flawed from inception.

The SGR included provisions for a conversion factor that would adjust payments to physicians annually. The idea behind this was if payments the previous year had exceeded the per-capita GDP, the conversion factor could be decreased the following year to account for this excess, thus cutting reimbursement. Each year this adjustment could be suspended or adjusted by Congress, and as scheduled cuts became increasingly drastic due to medical costs rising faster than the GDP, Congress repeatedly implemented legislation known as a “doc fix.” This was a temporary act of Congress to postpone the annual Medicare payment cuts to physicians — thus increasing the debt owed to the SGR the following year. This was done 17 times over 12 years, resulting in almost $170 billion dollars being spent by Congress in short-term patches to avoid these unsustainable cuts that reached as high as 27.4%.10-12

After 12 years of looming reimbursement cuts, Congress finally repealed the flawed SGR in April 2015 with the signing of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) by President Obama. MACRA established a stable physician reimbursement update of 0.5% annually until 2019, when the rates will be maintained and additional payment adjustments will be available by meeting certain quality measures.10 MACRA marks an important transition in Medicare reimbursement from being a solely fee-for-service model to one that will attempt to reward value and quality measures. Merit-Based Incentive Payments Systems (MIPS) and Advanced Payment Models (APMs) are two of the largest quality transformation projects in the program.

Private Payer Reimbursement

Private insurance companies are not required to reimburse physicians based on the RVU and SGR modalities that traditionally drove Medicare payments. While many of them do still utilize fee-for-service models, there has been a move toward more innovative reimbursement measures that attempt to reward quality, cost-efficiency, and encourage coordination of care between providers.

These agreed-upon contractual rates may be a percentage of what is actually billed, include quality incentives, and in some instances capitated amounts. While not required to follow CMS RVUs, the agreed-upon rates often fluctuate with changes in CMS pricing and follow a similar structure. For example, if the payment for an abscess drainage is decreased by CMS, then the private insurers will typically follow suit. Additionally, there is significant price variation between hospitals and insurers since, unlike CMS, pricing determination is impacted by external free market factors and is subject to geographical indexes in addition to concentration of both providers and insurers.13,14

Additional payment models will be discussed in upcoming chapters and include bundled payments for episodes of care, capitation models, value-based payment models, and Accountable Care Organizations. Many of these models are based on sum payments, which would involve a predetermined payment amount for a patient in a given time period, a specific procedure or hospital stay. This reflects a significant variation from the FFS model.14-17

Merit-Based Incentive Payments Systems

MIPS is a value-based care payment program created after the MACRA repeal of the SGR to consolidate multiple quality payment programs throughout CMS. MIPS is open to individual physicians and groups of physicians who bill for Medicare Part B, and it is estimated that 600,000 clinicians were enrolled in 2018.

Increased (or even decreased) reimbursement is tied to a 100-point score encompassing 6 value-based areas: quality, cost, advancing care information, improvement activities, small practice bonus, and complex patient bonus. If a score of 15 (for 2018, subject to change in future years) is not reached, a penalty may be applied to reimbursement for Medicare Part B patients. This penalty caps at a possible 5% reduction in payments for 2018, but the penalty will steadily increase over the next few years.18-20

WHAT'S THE ASK?

The repeal of the SGR and implementation of MIPS was a large step forward in payment reform; however, much is still unknown about the future of physician reimbursement. Effective advocacy will be required to ensure that the transition provides a stable environment for providers and patients. Advocacy can include:

- Staying informed about payment structures as large shifts are occurring with the implementation of MACRA and new private insurance company payment models.

- Learning about the new value-based program, MIPS, as a catalyst away from fee-for-service and toward value-based purchasing.

- Helping to design these new methods of reimbursement.