Ch. 22 - Telehealth

Adam Schefkind; Bryn DeKosky, DO, MBA; Adnan Hussain, MD

Telehealth, or virtual medicine, is the transmission of a patient’s medical information from an originating site to the physician or practitioner at a distant site via multimedia communication channels that minimally includes audio and video, permitting two-way, real-time interactive communication between the patient and distant site physician or practitioner. Advancements in technology allowing virtual communication have rendered telehealth a viable replacement for face-to-face communication in many cases. This can take many forms and varies among medical specialties.1 Importantly, disparities in available medical resources in different parts of the world have increased the need for telehealth. A Cochrane Review highlighted the utility of telemedicine, demonstrating non-inferiority to in-person care for the treatment of several chronic conditions.2 However, despite technological advances and increasing acceptance of telehealth, it remains a small part of overall health care — in 2016, just 0.3% of Medicare beneficiaries used telehealth, mostly for basic office visits and mental health services. Medicare beneficiaries using telehealth tended to be younger than 65, disabled, residents of rural areas, and afflicted with chronic mental health conditions.3

Telehealth, or virtual medicine, has the potential to grow within emergency medicine — and to encompass consultations from other specialties as well.

Emergency departments have applied telehealth in a multitude of ways.4 Early examples included transmittals of EKGs to cardiologists for remote consultations.4 Similarly, telestroke systems allow emergency physicians to consult with neurologists at stroke centers regarding patients with stroke-like complaints. These consulting physicians can remotely view CT scans and lab results, then videoconference to perform a basic exam. Another innovation is teletrauma, a system allowing trauma surgeons, emergency physicians, and

personnel on the scene of a trauma incident to communicate via video in real time.4 In this way, a referral center’s physicians can provide immediate advice on a patient’s need for imaging, surgery, transport, or transfer.4

As technology evolves, uses of telemedicine continue to increase. Smartphones have provided additional telehealth opportunities, a field known as “mhealth.” In 2013, emergency physicians at Los Angeles County Hospital tested a pilot system called TEXT-MED, allowing communication via text messages of instructions and reminders to high-risk diabetic patients after discharge from the ED;5 researchers found increased medication compliance and fewer ED bouncebacks by these patients.

Another telehealth pioneer is New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, which won the 2017 Emergency Care Innovation of the Year Award for its video express care program.6 That center’s ED provides an option to patients who present with non-emergent conditions to avoid waiting for an in-person physician visit, and instead videoconference from a private room with boardcertified emergency physicians at a remote site. ED wait times for patients using this system have decreased from 2–3 hours to approximately 35–40 minutes. Over the past few years, several hospitals nationwide have adopted similar programs.

Technology and Security

Interactions during telehealth usage commonly occur in three categories: live video consultations, remote monitoring, and “e-care” (capture and storage of patient data for future use).4 All three types of interactions generate significant amounts of data classified as protected health information (PHI). Under the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), any transmission of these data must be secure to maintain patient confidentiality. Expansion of telehealth thus poses challenges to ensure security of data transmitted from patients to health care providers. Hospital systems take many steps to protect the information technology (IT) infrastructure, but these security provisions are not in place when information is transmitted from a patient’s home Wi-Fi or cellular data network. Under these circumstances, if data are breached, who is responsible? Who is the custodian of data created during remote monitoring of patients?7

Rapid evolution of technology to support telehealth has included increased bandwidth, enabling high-definition video consultations, increased use of mobile health remote monitors, and wearable technology. With these advancements, generation of both intended and unintended health data has become ubiquitous. The legal system has yet to determine all of the liabilities and protections for this massive amount of data, and future laws and court decisions regarding this data will continue to shape the virtual health care landscape.

Reimbursements and Regulations

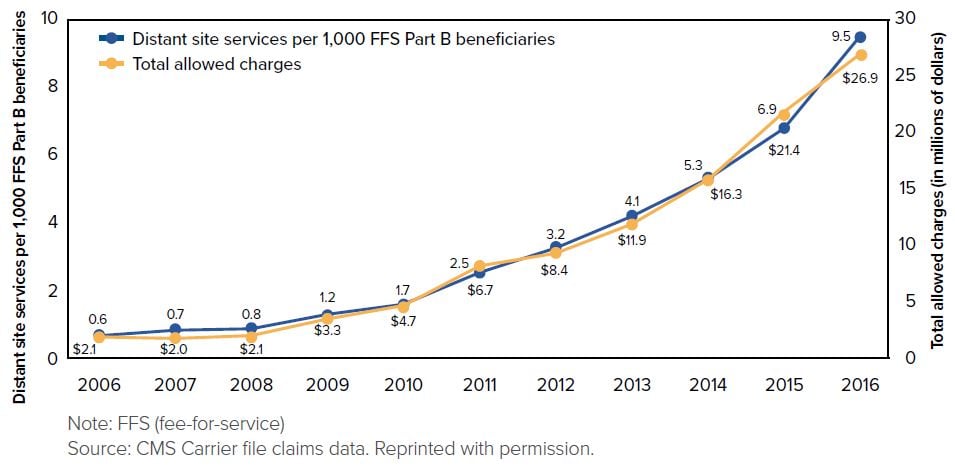

Early studies have shown that telehealth can reduce ED visits and increase compliance of patients afflicted with chronic conditions — reducing complications and ultimately insurance companies’ costs in the long term.2,8 Yet the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission noted in its 2018 Report to Congress that “commercial use [of telehealth] was low (less than 1% of plan enrollees).”3 ACOs often include telehealth in their coverage plans because of improved quality of care and costs savings it can provide,5,6 although MedPAC reported that for private commercial insurers, “competitive pressures from employers or other insurers” are the leading drivers of coverage by telehealth services.3 However, these cost savings are not a given. A RAND Corporation study in 2017 investigated commercial claims data pertaining to more than 300,000 patients during a 3-year period.9 Results of that research indicated that only 12% of telehealth visits replaced an in-person visit, whereas the other 88% involved new health care utilization. Net annual spending for the studied population actually increased by $45 per telehealth user. This study’s authors concluded that telehealth can lead to increased utilization of resources, and higher costs for the health care system.

Medicare has enacted numerous changes regarding reimbursement for telehealth.10,11 For example, reimbursements for telestroke consultations previously had been limited to “rural health professional shortage areas” or counties “not classified as... metropolitan.”12 The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 eliminated these geographic restrictions for telehealth management of acute stroke.11 It also allowed Medicare to cover use of telehealth for teledermatology, teleophthalmology, and home dialysis patients. This substantial expansion of direct-to-consumer care options may significantly affect ED utilization. Over the past several years, CMS has made multiple regulatory changes to enhance the utilization of telehealth, including creating new codes to allow physicians to bill for services provided remotely and allowing Medicare Advantage plans to include additional telehealth benefits.13,14 A trend toward increased acceptance and reimbursement of telehealth by insurers seems clear.14

FIGURE 22.1. Utilization of Medicare physician fee schedule distant site telehealth visits per 1,000 FFS Part B beneficiaries and total allowed charges for telehealth visits, 2006 to 2016

The regulatory environment varies greatly by state and is constantly evolving.15 For example, until 2018, Texas required a face-to-face encounter prior to a telehealth encounter. Texas also required that a telehealth encounter occur at a “clinical place of service.”16 However, Texas’s 2018 Senate Bill 1107 removed both of these restrictions with the caveat that the Texas Medical Board “is still authorized to make sure patients using telehealth services receive appropriate, quality care.”16 In 2018, 6 states imposed geographic restrictions on telehealth utilization, whereas 23 states limited reimbursement to a specific list of facilities.17 The “Telehealth Parity Law” passed in Washington state in 2015 mandated that reimbursement for services delivered via telehealth equal those delivered inperson.15

Licensing across state lines can be another barrier, as many states require that a physician be licensed to practice medicine in the state where the telehealth encounter will occur. Creating mechanisms to support portability of care across state lines is a major issue for telehealth providers.18 Significant opportunities are available for engagement with providers, payers, and legislators regarding advocacy to support telehealth programs. Evolution of laws and regulatory guidelines over time will be important to ensure support for improvements in technology and appropriate compensation.

Entrepreneurial Opportunities

Many physicians are expanding beyond the direct patient care arena to explore new opportunities in the evolving world of telehealth. Some physicians are starting their own telehealth consult services for direct patient care while others are setting up online tools and resources for patients to manage their own health care. A new model has emerged allowing emergency physicians to provide care via telehealth in nursing homes and rehab centers. One company practicing in this model, Call9, embeds highly skilled first responders (known as Clinical Care Specialists [CCS]) on site at these long-term facilities, offering patients 24/7 real-time access to emergency care. Via the CCS and Call9’s technology, physicians are able to meet, diagnose, and treat patients in their nursing home beds, potentially avoiding unnecessary trips to the ED and subsequent hospitalizations.19 Numerous similar companies have arisen over the past decade. For example, Teladoc employs licensed physicians (including a panel of emergency medicine doctors), and utilizes telephone and videoconferencing to offer remote urgent medical care to patients worldwide.20

Recent literature underscores the increased access to health care these companies have provided, but the question of effects on cost lingers. In fact, a recent cohort study published in JAMA described a significant increase in telehealth encounters from less than 1 visit per 1000 patients in 2008 to 6 visits per 1000 patients in 2015. However, these authors also noted a 14% increase in spending per person per year over that same time period.21 More research is necessary to determine the true impact of growth of telehealth on health care costs. During evolution of telehealth from these early adoptions to a stable part of the health care landscape, adventurous physicians will have many opportunities to participate in design and delivery of telehealth within these types of programs.

Future Potential

Telehealth could revolutionize the practice of medicine. The rapid pace of technological change and innovation has led to adoptions of telehealth in the acute care setting all over the country. A study by the New England Healthcare Institute found hospital readmissions were reduced by 60% with use of remote patient monitoring compared to standard care, and by 50% compared to disease management programs without remote patient monitoring.22 The same study estimated that remote patient monitoring could prevent between 460,000 and 627,000 heart failure readmissions each year, with an annual cost saving of $6.4 billion.22 Atrius Health, an independent health care organization, has stated that the rehospitalization rate of patients admitted to home care with their comprehensive telemonitoring program is 0-4% within the first 60 days of care. The national acute care rehospitalization rate for all patients receiving home health care services is 23%.23

In a different patient population, cost and use of telehealth visits and in-person visits for patients seeking treatment for acute respiratory infections (one of the most common conditions treated via telehealth services) underwent study based on 2011-2013 claims data from the California Public Employees’ Retirement System.24 The study found that only 12% of direct-to-consumer telehealth visits replaced a visit to another provider24 — despite the reasonable assertion that an individual may be less inclined to visit his/her primary-care doctor or visit the ED if afflicted with a common cold or a high fever, and that easy access and low cost of telemedicine should motivate people to seek a remote clinical consultation.24

Within the ED, telehealth has much room to grow. For example, integration of telehealth training into most residency programs has not yet occurred.25 Moreover, as telestroke and teletrauma become more widespread, potential expansion of telehealth to other specialty consultations (such as cardiothoracic surgery or ophthalmology) appears reasonable.26 Telehealth resources are currently underutilized in the ED, and their financial impact is yet to be determined.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Promote the adoption of a standard for transmission and storage of protected health information (PHI), so health care providers do not pre-emptively limit their adoption of virtual medicine due to privacy concerns.

- Advocate for adequate reimbursement to support development and integration of virtual medicine.

- Advocate for stable but responsive regulations governing the practice of virtual medicine to encourage and achieve broad adoption.