With the rising prevalence of neurosyphilis over the years, emergency medicine physicians should be cognizant of this can’t-miss diagnosis in patients with focal neurologic findings, new-onset dementia, progressive weakness, or unexplained psychiatric symptoms.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochete with clinical manifestations presenting in 4 different stages: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary.

Primary syphilis involves a painless chancre at the inoculation site usually 3 to 4 weeks after exposure. Secondary syphilis presents after the primary chancre with systemic symptoms and a rash known as condyloma lata.1

If syphilis is untreated in these stages, one then develops latent syphilis, in which there remains seroreactivity without any signs or symptoms. From this stage, one can re-develop secondary syphilis or progress to tertiary syphilis.

Neurosyphilis is a dangerous and increasingly prevalent sexually transmitted infection of the central nervous system that can present during the advanced stages of the disease, specifically tertiary syphilis.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports a 74% increase in syphilis cases (of all stages) from 2017 to 2021.3

With the rising prevalence of neurosyphilis over the years, emergency medicine physicians should be cognizant of this can’t-miss diagnosis in patients with focal neurologic findings, new-onset dementia, progressive weakness, or unexplained psychiatric symptoms.1 With untreated individuals, early neurosyphilis is resurging within high-risk populations including patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), men who have sex with men, patients with multiple partners, and those with limited access to health care. The prevalence of neurosyphilis among HIV-infected individuals with untreated syphilis has been reported as high as 23.5–40%, as compared to approximately 10% in HIV-uninfected individuals.4 Here we present a case of neurosyphilis in a reportedly healthy young man presenting with intermittent bilateral blurry vision.

Case

A 24-year-old male with no chronic medical problems presented to the emergency department with a 3-week history of intermittent bilateral blurry vision. He was evaluated 1 week prior by his ophthalmologist, and at that time, he was found to have bilateral disseminated chorioretinitis with concern for infectious etiology such as neurosyphilis, tuberculosis, or sarcoidosis. There were issues obtaining outpatient labs, so the patient was referred to the emergency department for further workup and potential admission.

On initial evaluation, the patient endorsed an episode of unprotected sex 4 months prior and noted that 2 months prior he developed 2 painless penile ulcers. He did not have any medical evaluation at that time, and the ulcers resolved.

Laboratory workup in the ED was notable for 93% lymphocytes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), anti-nuclear antibody 1:160, positive Treponema pallidum antibody, and RPR titer 1:128. Workup included negative CSF PCR panel and negative tests for HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and tuberculosis. The patient was admitted to medicine with a diagnosis of neurosyphilis and started on penicillin G 40 million units daily. Blurry vision did not recur during the hospital course after treatment was initiated.

The patient was discharged after 3 days with a PICC line in place and arrangement of home infusion services to continue treatment with penicillin G for a 10-day course. The patient was instructed to follow up outpatient with ophthalmology for a repeat eye examination to assess for resolution of his chorioretinitis.

Discussion

Untreated neurosyphilis can present with a wide differential of neurologic and cardiovascular sequalae. Depending on the progression of the disease in its early or late forms, these neurologic sequelae can manifest in a variety of ways. Early neurosyphilis may present as symptomatic meningitis with headache and confusion, otosyphilis, ocular syphilis and cranial nerve palsies. Late neurosyphilis may present with psychiatric disease such as depression and psychosis, dementia, as well as generalized paresis including degeneration of the posterior column.1 Ocular syphilis is an increasingly common clinical manifestation in immunocompetent as well as HIV-infected individuals.

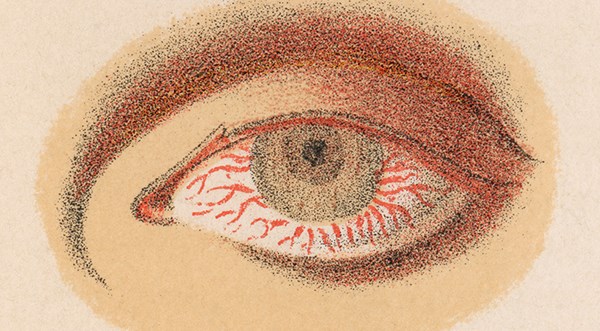

Ocular inflammation can occur at any stage of syphilis, and it may present as interstitial keratitis, uveitis, chorioretinitis, retinal vasculitis, and cranial nerve or optic neuropathies. Patients' initial chief complaints may include impaired vision, photopsia, and shadow blocking.5 Syphilitic chorioretinitis, specifically, can lead to severe vision loss. Literature review and case studies have indicated chorioretinitis to be a typical diagnostic sequela of neurosyphilis. It is often multifocal with a shallow retinal detachment and significant vitritis.6 A complete ophthalmologic examination, including pupillary examination, visual acuity, slit lamp biomicroscopy applanation tonometry, and fundus biomicroscopy, should be performed in all cases suspected to have neurosyphilis.

Diagnosis in the emergency department can be achieved through screening tests. If there is clinical suspicion of syphilis and a patient is serum antibody positive, a lumbar puncture is done to confirm the diagnosis based on CSF VDRL, WBC count, and protein content.2 The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test are useful screening tests to aid diagnosis. Lumbar puncture with CSF VDRL with elevated CSF lymphocyte count is diagnostic for neurosyphilis.7 This case report highlights the importance of CSF analysis in all patients diagnosed with ocular syphilis to rule out neurosyphilis, as the treatment strategy in patients with central nervous system (CNS) involvement is different from that for patients without CNS involvement.6

As emergency medicine clinicians, awareness of this can’t-miss diagnosis is crucial to patient care and management. Significant morbidity and mortality can be prevented with early diagnosis and treatment. Education on and encouragement of preventative measures such as getting adequately tested for sexually transmitted infections, treating pregnant patients with penicillin for latent syphilis to avoid vertical transmission, avoiding sexual activity during active disease, and use of barrier methods in high-risk populations is imperative.

References

- Tudor ME, Al Aboud AM, Leslie SW, et al. Syphilis. [Updated 2023 May 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534780/

- Marra, C. UpToDate. Neurosyphilis. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neurosyphilis. Accessed January 2024.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STi Statistics: Sexually Transmitted Infections Surveillance. 2023.

- Pialoux G, Vimont S, Moulignier A, Buteux M, Abraham B, Bonnard P. Effect of HIV infection on the course of syphilis. AIDS Rev. 2008;10(2):85-92.

- Yang B, Xiao J, Li X, Luo L, Tong B, Su G. Clinical manifestations of syphilitic chorioretinitis: a retrospective study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(3):4647-4655. Published 2015 Mar 15.

- Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis Ocular Manifestations. [Updated 2023 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558957/.

- Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(2):187-209.