Central retinal artery occlusion is an ocular emergency that commonly presents as sudden, painless, monocular vision loss. It can be a harbinger of serious comorbidities, making diagnosis important. POCUS has shown to be a quick and easy way to diagnose CRAO in the emergency department.

Editor's note: Thanks to faculty and peer reviewers Ochan Kwan, MD, St. Barnabas Emergency Medicine PGY4, and Allen Gold, DO, Assistant Director, Division of Ultrasound, St. Barnabas Emergency

Case

A 70-year-old female with no known past medical history presented to the ED for evaluation of sudden-onset left eye vision loss. She reported that she went to bed around 8:30 pm the night before and woke up at 9:30 am with a severe left-sided headache that was followed by complete, unilateral loss of vision in her left eye. She denied any other associated symptoms, including numbness, paresthesias, or weakness.

Physical Exam

Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 155/64 mmHg, heart rate of 96 beats per minute, temperature of 98.7° F, respiratory rate of 23 breaths per minute, and SpO2 95% on room air.

On physical exam, bilateral conjunctivae were clear without any injection, discharge, or scleral icterus. Pupillary exam was notable for a relative afferent pupillary defect on the left eye. Her right pupil was reactive to light and accommodation. Her visual acuity evaluation revealed complete left eye visual field vision loss with intact light perception. The vision in her right eye remained at baseline. Her extraocular movements and the remainder of her cranial nerves remained intact.

She exhibited no dysarthria or facial droop and had full strength and sensation in bilateral upper and lower extremities. There was no tenderness or fullness to her temporal regions.

Labs and Imaging

The patient was evaluated for acute stroke and received a non-contrast CT head that was negative for acute abnormality. She also had a CT angiography of the head and neck that showed atherosclerotic disease of the carotid arteries without acute occlusion. Notable labs included ESR at 64 and CRP at 3.4, but were otherwise unremarkable.

POCUS Ocular Exam

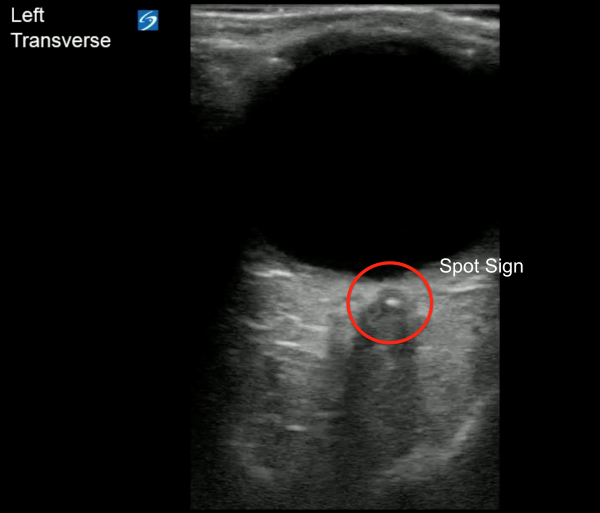

An ocular point-of-care ultrasound was performed on the patient's left eye while in the ED. A linear probe was utilized on the ocular setting. The operator fanned through the eyeball in both the sagittal and transverse axes to visualize the structures of the eye. The relevant anatomy of the eye can be seen in Image 1, with a video clip of normal anatomy seen in Video 1.

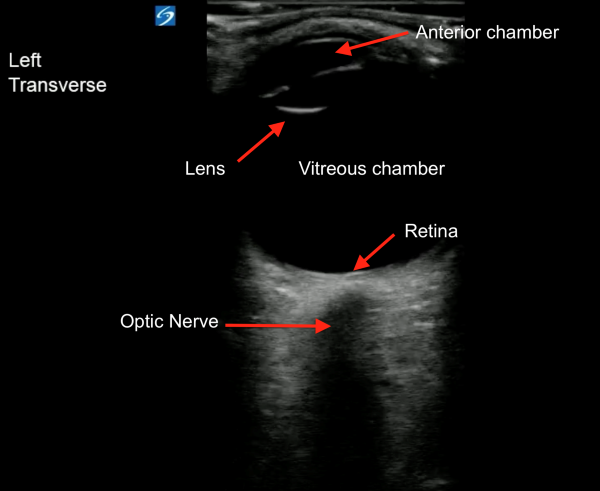

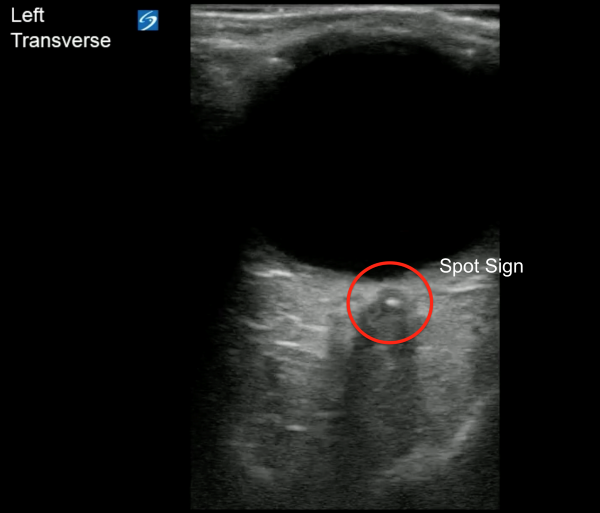

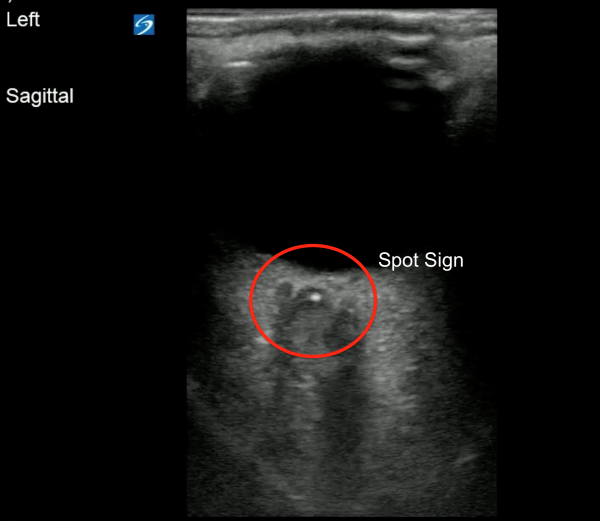

On this patient's ultrasound, a hyperechoic density was seen in the optic nerve sheath just distal to the retina (Video 2, Video 3). This was recognized as a "retrobulbar spot sign," which is concerning for a central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) (Image 2, Image 3).

Image 1. Relevant anatomy of the eye

Video 1. Normal eye, transverse view

Image 2. Retrobulbar spot sign, transverse view

Video 2. Retrobulbar spot sign, transverse view

Image 3. Retrobulbar spot sign, sagittal view

Image 3. Retrobulbar spot sign, sagittal view

Discussion

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is an ocular emergency that commonly presents as sudden, painless, monocular vision loss. It is caused by either partial or complete blockage of the retinal artery. The incidence is thought to be approximately 1-2 in 100,000.1 The mean age of those affected is 60-65 years, and it affects males more often than females.1 The most common etiology overall is carotid artery atherosclerosis.2 Other causes include embolism from the heart or carotids, as well as hypercoagulable states, hematologic conditions, giant cell arteritis, and other vasculitides.1 Risk factors for CRAO are identical to those of other vascular diseases like strokes or coronary artery disease, and may include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking.2

POCUS has shown to be a quick and easy way to diagnose CRAO in the ED. When evaluating the optic nerve, a hyperechoic “spot” can be seen, thought to be a calcification or clot in the retinal artery.3 This is referred to as the spot sign. One study found that the spot sign on ultrasound had a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 100% for detection of an embolic CRAO.4 Another study found that identification of the spot sign was found to have high interobserver agreement, which suggests that CRAO could be easily detected among ED physicians.5

Identification of the spot sign may even provide insight into the cause of the CRAO.6 In a prospective study of patients with CRAO, 46 patients were classified based on the cause of their occlusion. The causes included cardioembolism, large artery atherosclerosis, vasculitis, and undetermined cause. Interestingly, 59% of the patients with large artery atherosclerosis displayed a spot sign on ultrasound, compared to only 20% of the patients with cardioembolism, and 0% of the patients with vasculitides.6

Lastly, a spot sign may help predict a patient’s response to therapy.6 In a small prospective study of 11 patients with CRAO who received tPA, 4 were spot sign negative and 7 were spot sign positive. All of the spot sign-negative patients had improvement in their visual acuity after thrombolytics, while the spot sign-positive patients did not.6

Ultimately, additional research is needed to further support the spot sign as a diagnostic and prognostic modality for CRAOs. However, the current data highlights the potential utility and ease of POCUS as a diagnostic modality for identifying CRAO. This is especially true when compared to traditional fundoscopy, which is likely utilized far less by emergency physicians.8

Management of CRAO

Patients who present within 4.5 hours of symptom onset may receive tPA as treatment for CRAO.2 For those outside this window, there are a variety of other treatment options. For example, reduction of intraocular pressure can be attempted, either through medications like acetazolamide or mannitol, or through anterior chamber paracentesis.1,2 Vasodilatory medications like pentoxifylline or nitroglycerin can be used to improve ocular blood flow.1,2 Ocular massage may be used to improve retinal perfusion and attempt to dislodge the embolism.2 Lastly, hyperbaric oxygen therapy can be used as a temporizing measure while waiting for definitive reperfusion.2 Additional treatment options such as intra-arterial thrombolytics and surgical revascularization are still being studied.2

Both Ophthalmology and Neurology are typically involved in management of these patients. At this time, there are no definitive evidence-based treatment guidelines for CRAO.9 Some patients may experience spontaneous recovery of vision, however the overall prognosis is poor.2

Hospital Course and Resolution

This patient was evaluated by Neurology and did not receive tPA, as she was outside the 4.5-hour window. They agreed with the concern for CRAO; however, they recommended treatment for giant cell arteritis as well, given the patient's elevated inflammatory markers. She received a 5-day course of IV methylpredisolone, and underwent biopsies of the temporal arteries (performed by Vascular Surgery). Biopsies were subsequently negative for temporal arteritis.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy was recommended by Ophthalmology, for which she completed 5 treatments while inpatient. She had an MRI of the brain and orbits that revealed acute supratentorial and infratentorial infarcts in multiple vascular territories, concerning central embolic etiology per Radiology. Her formal echocardiogram showed a dilated right atrium, raising the question of atrial fibrillation as a cause, despite being in normal sinus rhythm throughout her hospital stay. Her echo also revealed severe mitral annular stenosis, which was thought to be another potential source of embolism. She was started on aspirin, atorvastatin, and received an insertable loop recorder with Cardiology.

The patient was discharged home to follow up with outpatient Cardiology and was ultimately prescribed apixaban. Unfortunately, she had persistent vision impairments in her left eye.

References

- Sim S, Ting D. Diagnosis and Management of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion. Fekrat S, Scott I, eds. EyeNet Magazine (American Academy of Ophthalmology). Published online Aug. 1, 2017.

- Hedges T. Central and Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion. UpToDate. Published July 6, 2023.

- Caja KR, Griffith KM, Roth KR, Worrilow CC, Greenberg MR, Doherty TB. Detection of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion by Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Emergency Department: A Case Series. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16142.

- Ertl M, Altmann M, Torka E, et al. The Retrobulbar “Spot Sign” as a Discriminator Between Vasculitic and Thrombo-Embolic Affections of the Retinal Blood Supply. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(7):e263-e267.

- Czihal M, Lottspeich C, Köhler A, et al. Transocular sonography in acute arterial occlusions of the eye in elderly patients: Diagnostic value of the spot sign. PloS one. 2021;16(2):e0247072-e0247072.

- Nedelmann M, Graef M, FrankWeinand F, et al. Retrobulbar Spot Sign Predicts Thrombolytic Treatment Effects and Etiology in Central Retinal Artery Occlusion. Stroke. 2015;46(8).

- Farhan Q, Ramzan J, Alina C. Using Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Early Identification of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion. Int J Crit Care and Emerg Med. 2022;8(1).

- Mackay DD, Garza PS, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. (2015). The demise of direct ophthalmoscopy: A modern clinical challenge. Neurology Clin Pract. 2015;5(2):150-157.

- Chen C, Singh G, Madike R, Cugati S. Central retinal artery occlusion: a stroke of the eye. Nature: 2024;38:2319-2326.

- Stoner-Duncan B, Morris S. Early Identification of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion Using Point-of-care Ultrasound. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(1):13-15.

- Emiliya Usheva, Williams D, Musgrave H, Zhou S. Sonographic Retrobulbar Spot Sign in Diagnosis of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: A Case Report. J Educ Teach Emerg Med. 2023;8(4):V5-V8.

- Schnieder M, Fischer-Wedi CV, Bemme S, Mai-Linh Kortleben, Feltgen N, Liman J. The Retrobulbar Spot Sign and Prominent Middle Limiting Membrane as Prognostic Markers in Non-Arteritic Retinal Artery Occlusion. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2):338.

- Taylor GM, Evans D, Doggette RP, Wallace RC, Flack AT, Kennedy SK. Painless loss of vision: rapid diagnosis of a central retinal artery occlusion utilizing point-of-care ultrasound. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2021;6:omab038.

- Chen AX. SAEM Clinical Images Series: Retrobulbar Spot Sign. ALiEM. Published January 29, 2024. Accessed July 27, 2024.

- Smith A, Wilbert C, Ferre RM. Using the Retrobulbar Spot Sign to Assist in Diagnosis and Management of Central Retinal Artery Occlusions. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;39(1):197-202.