A 55-year-old male with a history of pancreatic cancer presents with his wife to the ED with jaundice, dark urine, and malaise for one week.

He has been following up with his oncologist and primary care doctor, and he explains there are no other viable options for treatment of his cancer and he will likely die within the next month. He would like to be at peace in his final days and wants to transition his care to focus on his comfort. He has home health nursing 24/7 given his significant decline recently. Though sad given the circumstances, his wife is in agreement and is ready to support him with his decision.

End of Life in the ED

We are often confronted with patients presenting to the ED in the final days of their lives, whether they are acutely decompensating or on a less acute trajectory toward death. There has recently been more recognition of the importance of having early goals of care discussions involving patients and their families and the initiation of palliative measures in the emergency care setting.1 Some patients and families have made clear decisions regarding end-of-life care before they enter the ED, and others may not consider these decisions until they arrive. In other instances, patients and their health care decision-makers have decided not to undergo aggressive measures such as intubation and CPR, but still may be agreeable with some degree of artificial hydration, blood products, or antibiotics.

For those who present to the ED looking for assistance with end-of-life care, the ED care team can help to coordinate first steps. Time should be taken to establish rapport with the patient and their family and to assess understanding of the situation. Medications will be an important part of assuring comfort. Documenting and completing a physician order for life sustaining treatment (POLST) form and an out-of-hospital do-not-resuscitate (DNR) form should be completed.

Comfort Measures

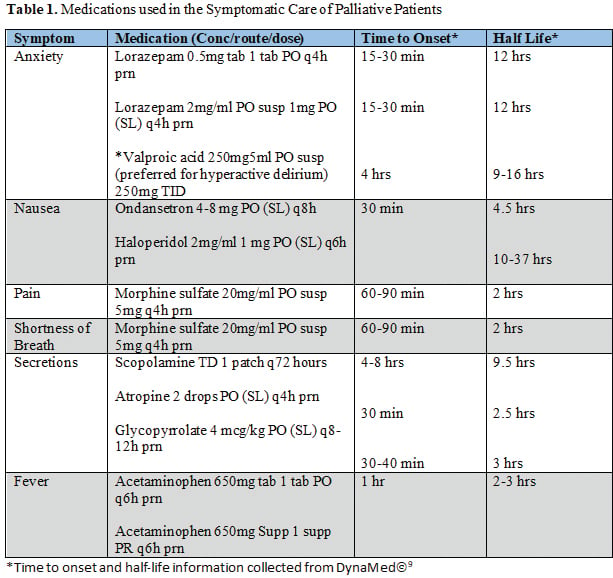

When a patient or family members decide to focus on comfort as the primary goal of care, management changes significantly. Comfort measures include far more than simple pain control, which may be a challenge on its own. Patients may struggle with dyspnea, which can lead to anxiety. Other commonly recognized symptoms requiring aggressive management include difficulty clearing secretions, nausea and vomiting, fevers, delirium/agitation, and pressure ulcers. Traditionally, this care has been initiated in the hospital setting, ICU, or palliative medicine unit, although recently there has been more focus on initiating these measures in the ED.2 Early initiation of palliative care has led to decreases in length of hospital stay, decreases in costs of care, and increases in patient and family satisfaction with care received.3,4 As long as a patient is hemodynamically stable, comfort measures may be initiated in the ED and continued on an outpatient basis.2

Whether intended as the totality of care or as a bridge to hospice, comfort care discharge orders can avoid a costly hospital stay and allow patients and their family to have meaningful time together in the comfort of their home or in a nursing home. The orders placed for outpatient palliative care and comfort care should aim to control the same symptoms as inpatient orders. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, care should be taken to consider services a patient may already have access to, including nursing home care, skilled nursing, or home health services, and orders should be tailored accordingly. For example, many medications are given intravenously in the hospital, but this may not be an option for a patient in an outpatient setting. Similarly, a patient may be unable to tolerate swallowing medications. Familiarity with medication options and routes of administration will go a long way toward optimizing outpatient comfort. Anticipating the patient's needs and caregiver level of comfort should also be a priority. Family should be counseled on what signs/symptoms to expect and how they should respond as well as being given resources to reach out to if they become overwhelmed or have questions.

Symptom Control

The most common symptoms to address are pain, dyspnea, nausea, and agitation.5 While opioids may provoke controversy in other cases, they are invaluable in the management of pain and dyspnea in end-of-life care. There are many things to consider when attempting to control pain in end-of-life care, including history of opioid use, severity of pain, presence of end-organ dysfunction, and age.6 For example, kidney failure can impede clearance, or morphine metabolites and liver failure can impair metabolism of morphine itself. This may necessitate using an alternative such as fentanyl or hydromorphone. Knowing the basics about opioid metabolism can help with dosing. Opioid requirements may increase as the end-of-life approaches. Opioids also have the benefit of fighting air hunger.

Agitation and delirium may also be a significant source of distress to the patient and caregivers. Benzodiazepines are first-line, although antipsychotics can also be helpful. Benzodiazepines, however, may cause a paradoxical reaction leading to agitation in the setting of delirium. An ideal first choice for anxiety is lorazepam given its quick onset of action. Another choice for agitated delirium, which has shown utility in ICU settings, would be valproic acid.7

Nausea and vomiting may be controlled with antiemetics. Ondansetron is a common choice, and dosing is familiar for most physicians. Ondansetron also has the benefit of having a dissolvable form for patients who cannot tolerate swallowing. For refractory nausea and/or cancer-related nausea, an excellent choice is haloperidol.8

Secretions may also be an issue for patients as they can impair breathing and create an unsettling “death rattle.” Educating caregivers on gentle and frequent suctioning can go far to combat secretions. Anticholinergics are the drugs of choice to control secretions, and popular choices are scopolamine patches, glycopyrrolate, and atropine. Scopolamine patches should be applied once a day. Atropine and glycopyrrolate can be applied sublingually but require more frequent dosing. Anticholinergics have been found to be associated with agitation in delirious patients.

Case Resolution

A long discussion was held with the patient and his wife about what to expect in the coming days to weeks. The patient and his wife went through the process of clearly identifying his wishes on a POLST form and an out-of-hospital DNR. He noted significant problems with anxiety, nausea, and pain, and options were explored to augment his existing home medications. Prescriptions and clear instructions were provided for the patient and his home health nurses. Messages were sent to his primary care doctor and oncologist informing them of the patient’s decision, and a referral to palliative care was placed. The patient returns home with his wife, and several weeks later you receive a message from his wife thanking you for helping make his last days comfortable at home.

References

- George NR, Kryworuchko J, Hunold KM, et al. Shared decision making to support the provision of palliative and end-of-life care in the Emergency Department: A consensus statement and research agenda. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2016;23(12):1394-1402. doi:10.1111/acem.13083

- Leith TB, Haas NL, Harvey CE, Chen C, Ives Tallman C, Bassin BS. Delivery of end‐of‐life care in an emergency department–Based Intensive Care Unit. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1500-1504. doi:10.1002/emp2.12258

- DeVader TE, Albrecht R, Reiter M. Initiating palliative care in the emergency department. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;43(5):803-810. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.035

- George NR, Kryworuchko J, Hunold KM, et al. Shared decision making to support the provision of palliative and end-of-life care in the Emergency Department: A consensus statement and research agenda. Academic emergency medicine: Official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Published December 2016. Accessed November 20, 2021.

- Wang D, Creel-Bulos C. A systematic approach to comfort care transitions in the emergency department. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. Published December 29, 2018. Accessed November 20, 2021.

- Goldstein NE, Morrison RS, Goldberg GR, Smith CB. 1. How Should Opioids Be Started and Titrated in Routine Outpatient Settings? Evidence-Based Practice of Palliative Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2013:2-7.

- Crowley KE, Urben L, Hacobian G, Geiger KL. Valproic acid for the management of agitation and delirium in the intensive care setting: A retrospective analysis. Clinical Therapeutics. 2020;42(4). doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.02.007

- Cassone M, Stoltzfus G, Melnychuk E. Terminal extubation in the ED: Palliative care in em. EMRA. https://www.emra.org/emresident/article/terminal-extubation/. Published August 17, 2020. Accessed November 20, 2021.

- DynaMed [database online]. Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. https://www.dynamed.com. Accessed November 20, 2021.