Providing palliation and end-of-life care has become an important aspect of emergency medicine; this has become especially relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comfort measures and terminal extubation may be among the most important procedures you perform during a shift.

Toward the end of your shift, EMS presents with a 94-year-old female found obtunded in her home by neighbors after an unknown period of time. She required intubation in the field by the paramedic for depressed level of consciousness; neither family nor a POLST form were available on scene. Her vitals are stable on arrival and she has a history of hypertension, prior ischemic stroke, and atrial fibrillation on coumadin. Her CT shows a large intraparenchymal hemorrhage with intraventricular extension and midline shift. Her bleed is deemed to have poor chance of recovery by the EM, Neurology, and Neurosurgery Teams. A discussion with her children who have arrived at bedside reveals that she did not want to receive aggressive treatment or be on a ventilator for any period of time. The decision is made to transition to comfort measures. Your ICU is at full capacity and you are boarding critical care patients in your ED; therefore, you make the decision to terminally extubate the patient in the ED and transition her to the palliative care service.

Palliative Care in the ED

Palliative care is a growing topic of interest in EM. Greater than 50% of geriatric and 80% of metastatic cancer patients visit the ED within the final months of life.1 Beyond discussions of advance directives, goals of care, POLST forms, and hospice services, providing palliation and end-of-life care has become an important aspect of emergency medicine. Providers likely will be faced with the need to terminally extubate a patient in the ED during their careers; this has become especially relevant in this time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comfort measures and terminal extubation may be one of the most important procedures you perform during your shift.

Teamwork and Communication

Goals of care discussions and breaking bad news are fundamental skills for an EM clinician. Once the decision to transition to comfort care has been decided, effective communication with family members is key to understanding their wishes and setting expectations. Several studies have shown that open and clear dialogue with families regarding their relative’s wishes and symptom management contributed to higher family satisfaction during end of life care in ICUs.2,3 Ensure you have thoroughly explained the steps that will take place and signs of the dying process that family may notice. Reinforce that your team will be attentive to keeping the patient comfortable. If possible, consider moving the patient to a private room in a quieter section of the department with more room for family members and loved ones. A sign on the door indicating the need for privacy can be considered. Ensure the nursing team and respiratory therapists are aware of the plan and prioritize patient and family comfort. Consider speaking with organ donation services, social workers, and spiritual care if requested by family as well your hospital’s palliative care team.

Preparing Your Patient

Prior to terminal extubation, consider several steps to prepare the patient. This will be the last time family members will be able to see their loved one alive. Therefore, compassion and respect for the patient, family and loved ones are paramount. Attempt to organize the room and provide the patient with enough blankets and pillows. Adjust clothing or hospital garb for the patient.

Anecdotal evidence indicates aspiration and emesis can sometimes occur during the process of terminal extubation: consider decompression of the patient’s stomach contents with a nasogastric tube if already in place. The care team should remove blood pressure cuffs, telemetry leads and any other monitoring devices in the room; this ensures a peaceful environment for the patient and limits additional stress to family. If remote-only monitoring is possible, providers may consider leaving only finger pulse-oximetry to monitor waveform/pulse on telemetry to note time of death. If a prolonged course is expected and it does not provide discomfort to the patient, urinary catheters may remain in place at the provider and family’s discretion; condom-catheters may be considered in male patients as a less intrusive option. Wound care in patients with traumatic injuries should be limited to limit odor and drainage and preserve patient dignity.

If the patient is on vasopressors, IV fluids or receiving any other non-palliative interventions these should be stopped prior to terminal extubation. Patients with automated implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (AICD) should have the defibrillator function deactivated with a ring magnet and left-ventricular assist devices (LVAD) can be disconnected from their battery source or driveline controller unit. Depending on your state guidelines and patient’s presentation, endotracheal tubes (ETT) and IV access must remain in place prior to evaluation by the local coroner’s office. Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment may be delayed in order to achieve appropriate and anticipatory symptom management. Delaying withdrawal of care for family arrival or spiritual rites should be considered by the provider but not unduly prolong suffering of the patient.

Medications

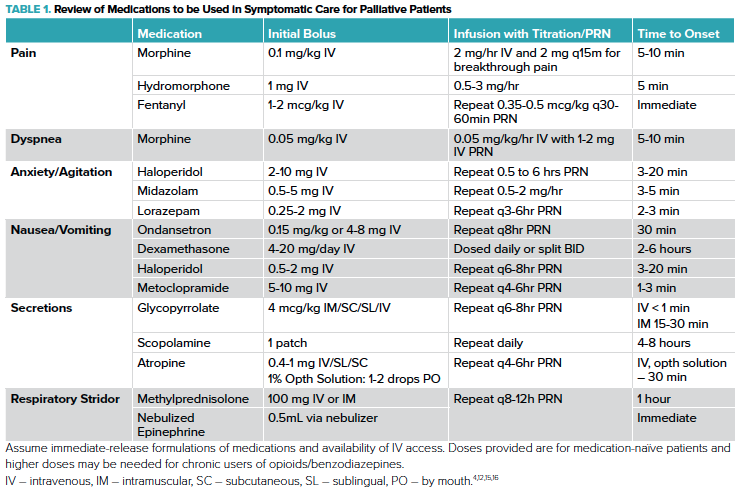

Prior to terminal extubation, providers should actively treat any symptoms the patient is experiencing as well as anticipate symptoms that may occur after extubation. Opioids, benzodiazepines, and anticholinergic medications are the cornerstones of pharmacotherapy of the dying patient. Appropriate, early and frequent re-dosing are key to ensuring the patient remains comfortable during the dying process.

Opioids play a large role in palliative care for the management of both pain and dyspnea. Morphine is a mainstay of palliative care, but providers may also choose to use hydromorphone or fentanyl (Table 1). Bolus dosing of morphine in opioid-naïve patients typically starts at 0.1 mg/kg IV for analgesia or 0.05 mg/kg IV for air hunger.4 This should be repeated every 15-30 minutes to achieve desired effect and may require significantly higher doses for patient chronically taking opioids.5 Maintaining adequate serum levels can then be achieved with infusions, long-acting formulations, or repeated dosing. Infusions are particularly useful for the ease of titration. For example, a morphine infusion of 2 mg/hr and 2 mg IV q15min for breakthrough pain or RR > 18 with increase in rate by 1 mg/hr if 3 or more PRNs are used within one hour is one commonly used approach.4 Doses may need to be titrated up to 10 mg/hr or more, particularly in patients with chronic opioid use or severe respiratory failure.5

Providers may be concerned about using opioids in comfort-care patients due to the theoretical effect of depressing respiratory drive and thus hastening death. This is known in palliative care as the “double-effect”. Providers have a legal and ethical mandate to provide appropriate comfort as a primary goal, even if this may hasten patient death as a secondary effect.4 However, there is evidence that when opioids are titrated for subjective respiratory comfort, they do not significantly alter PaCO2, PaO2, or overall survival.6 In fact, appropriately elevated morphine dosing has been associated with no change or a longer time to death.5, 7 However, opioids are certainly not benign medications and providers should be ready to manage side effects including histamine response and nausea.

Patients nearing end of life may also be experiencing anxiety, and/or delirium. Mainstays of treatment will include benzodiazepines and antipsychotics (Table 1).4 These medications will need to be titrated to effect with significant ranges in effective doses due to many factors including age, gender, renal/hepatic function, and prior exposure to these medications. A patient’s comorbidities and prognosis may influence your medication choice, i.e., use of lorazepam for patients with hepatic impairment or midazolam when faster onset is a priority.

Some patients may experience nausea or vomiting and are particularly at risk following extubation and with the use of opioids. Ondansetron is a commonly prescribed antiemetic and may be particularly effective in patients receiving chemotherapy. Dexamethasone may also alleviate nausea related to chemotherapy use.8 Metoclopramide should be considered if gastroparesis or stomach compression are thought to be contributory.8 Finally, dopamine antagonists can be effective for refractory nausea.8

Secretions commonly contribute to the anxiety of family members and loved ones due to the characteristic death rattle.9 Anticholinergics can be provided to decrease secretion production with glycopyrrolate and scopolamine showing equivalent efficacy.10 These medications only limit new secretion production so they may take time to effectively show a change in symptoms. Frequent, gentle suctioning is key. Atropine ophthalmic drops work quickly and may be administered PO if IV access is not possible or the patient’s skin is not amenable to patches.10 (Table 1)

When choosing medications to address symptomatic care and preparation for terminal extubation, EM providers should consider onset of action, half-life, and dosing. Unlike patients that have been admitted for hours or days, patients arriving in the ED have not yet received prior treatment or reached therapeutic levels. An initial bolus followed by infusion or long acting medications is generally necessary. Building flexibility into your orders via titration and/or PRNs will allow your team to meet patient needs in a setting where patients will need to be frequently re-evaluated. Having additional PRN doses available at bedside during the extubation process can help in avoiding delays in treatment. Intravenous medications are preferred due to the faster rate of onset and the ease of titration. If IV access is unavailable providers may consider buccal, nasal, subcutaneous, oral, or intramuscular routes for certain medications. (Table 1) The care team should monitor the patient closely for signs of distress including fist-clenching, tears, grimacing, tachycardia, diaphoresis, tachypnea, accessory muscle use, and nasal flaring. Standardized assessments scales such as Sedation-Agitation Score (SAS) or the Ramsay Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) may provide additional input. Ketamine is not routinely recommended by several guidelines due to concerns for emergence reactions.11-14 Paralytic agents during terminal extubation are not recommended as they may blunt the care team’s ability to assess the patient for signs of distress and may unnecessarily hasten the dying process. 11-14 Propofol may be considered as a sedative/anxiolytic and has anti-emetic properties. 13

Terminal Extubation

Once the patient has been adequately medicated and other life-sustaining measures stopped, the patient can be considered for terminal extubation. There are two general techniques for removing a patient from ventilator support- terminal extubation and terminal wean- each with various indications and outcomes.4,11,13,17-20 Terminal extubation (without a slow taper in respiratory support) may be considered in patients without significant respiratory compromise (ie: those intubated for depressed GCS) and still have a gag reflex. Terminal wean is preferred when there is concern for respiratory compromise (ie, ARDS, pulmonary edema, COPD).

To perform a terminal wean, patients should be placed on IMV or PS mode and then should have a step-wise decrease in the FiO2 to 40% and PEEP to 5 cm H2O. At each step-down, the patient should be reassessed for signs of air hunger or agitation and receive appropriate bolus dosing and up-titration of infusions to match symptoms. The RSBI (Rapid-Shallowing Breathing Index: respiratory rate divided by tidal volume) can be used to determine level of distress.4 The terminal wean is usually performed over 10-60 min depending on the patient.4,12 Once the ventilator settings have been weaned and the patient’s symptoms addressed, the provider can consider extubating the patient. If imminent loss of airway or significant respiratory distress is anticipated during weaning or removal of the ETT, several guidelines suggest a proactive rather reactive approach using aggressive palliative sedation.4,12

When performing the extubation, have suction ready, turn off the ventilator alarms, and have a respiratory therapist at bedside if possible. Consider draping the patient's chest with absorbing pads during the extubation to prevent secretions and blood landing on their gown. Providers should consider wearing PPE depending on the circumstance as this can be an aerosol-generating procedure. Once off ventilator support, guidelines vary on removal of the ETT.11,13,18 Many providers will remove the ETT for patient comfort and family request. However, in some cases such as massive hemoptysis, major facial trauma, significant secretions or swollen tongue the patient may be more comfortable with the ETT kept in place with a T-piece and humidified air. If stridor is anticipated or noted post-extubation, providers may give nebulized epinephrine or steroids such as methylprednisolone to help with symptom management (Table 1).11,21 In general, guidelines do not recommend transitioning to non-invasive ventilation after extubation.14

Setting Expectations

Family members may inquire how long the dying process will take and what symptoms may occur. Answering these questions can be difficult but important for anticipating symptom management, family expectations, and disposition. On average, ICU patients survive between 35 minutes to 7.5 hours after terminal extubation.11 Providers must be able to recognize key symptoms that require interventions in the dying patient. The most common symptoms requiring intervention include fatigue (28.7%), pain (22.1%), and respiratory distress (22.1%).22 Several studies have shown that it is difficult for providers to accurately predict time of survival in individual patients after extubation.11,22,23 The death rattle (sound of secretions pooling in the hypopharynx and bronchial tree), respiration with mandibular movement, Cheyne-Stokes respirations, and cyanosis of extremities are common symptoms in the dying patient, however none is specifically predictive of imminent death (can be noted hours to days before death) or used to accurately predict duration of survival.24 Other factors such as GCS score, SpO2, and the amount and duration of sedation/analgesia required have also not been found to be predictive of time of death.11 It is important for providers to communicate these uncertainties to families when setting expectations.

Improving the Process

Providing end-of-life care in the ED is an essential skill for EM providers. The ABEM Model of Clinical Practice includes palliative care as an essential part of residency training.25 Programs should consider including didactics and simulations on end-of-life discussions and terminal extubation. Residents can continue to improve these skills and the processes in their departments by providing dedicated training to fellow residents, nursing, and ancillary ED staff, discussing guidelines with department leadership and debriefing sessions after individual cases. Several guidelines exist that providers may reference.12,13,26,27 Palliative care, and particularly the process of terminal extubation, does not make for an easy shift. Transitioning from managing a critically ill patient to the application of comfort care is taxing for patients, families, and health care teams. Clear communication, establishing an appropriate environment, aggressive management of symptoms, and understanding the concepts of terminal extubation will help ensure a compassionate and dignified process for your patients and their families.

Case Resolution

After discussing the plan with both the patient's family and nurse, you move the patient to a private room designated for end-of-life care. The nurse administers a bolus dose and infusion of morphine. Once your patient appears comfortable, the respiratory therapist terminally extubates the patient. You and the nurse frequently re-assess the patient for additional PRN doses of medications and gentle suctioning as needed. After monitoring for 40 minutes and checking with family, your patient continues to have a faint pulse and SpO2 around 84%. You discuss with the palliative care team, who admits her to their service. Your patient passes away peacefully 6 hours later with her family at bedside.

Take-Home Points

- When transitioning a patient to comfort care and performing terminal extubation in the ED, maintain open and clear communication with your patient, their families, nursing and ancillary staff.

- It is important to set the scene. Establish a private space, turn off monitors, and avoid unnecessary procedures to reflect the respect and compassion this situation deserves.

- Be aware of and closely monitor symptoms associated with the dying process. Appropriate medications such as opiates, benzodiazepines, and anticholinergics should be given early and as frequently as needed.

- Be familiar with the process of terminal extubation. Understanding the preparatory steps and post-extubation care are essential to ensuring a comfort-oriented, compassionate and dignified process for your patient. Training and establishing departmental guidelines can help ease what can be a difficult process.

REFERENCES

1.Obermeyer Z, Clarke AC, Makar M, Schuur JD, Cutler DM. Emergency care use and the Medicare Hospice Benefit for individuals with cancer with a poor prognosis. American Geriatrics Society. 2016; 64(2): 323-29.

- Gerstel E, Engelberg RA, Koepsell T, Curtis JR. Duration of withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit and association with family satisfaction. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2998; 178(8): 798-804.

- Hinkle LJ, Bosslet GT, Torke AM. Factors associated with family satisfaction with end-of-life-care in the ICU. Chest. 2015; 147(1): 82-93.

- Wang D, Creel-Bulos C. A systematic approach to comfort care transitions in the Emergency Department. J of Emerg Med. 2019; 56: 267-74.

- Mazer, MA. The infusion of opioids during terminal withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in the medical intensive care unit. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011; 42(1):44-51.

- Clemens KE, Klaschik E. Symptomatic therapy of dyspnea with strong opioids and its effect on ventilation in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007; 33: 473-81.

- Sykes N, Thorns A. The use of opioids and sedatives at the end of life. Lancet Oncol. 2003; 4: 312-18

- Zalinski RJ, Zimmy E. Palliative Care. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 2016.

- Gray MY. The Use of Anticholinergics for the Management of Terminal Secretions. Evidence Matters. 2007; 1(3).

- Kintzel PE, Chase SL, Thomas W, Vancamp DM, Clements EA. Anticholinergic medications for managing noisy respirations in adult hospice patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009; 66: 458-64.

- Campbell ML. How to withdraw mechanical ventilation: a systematic review of the literature. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007; 18(4): 397-403.

- Kompanje EO, Van der Hoven B, Bakker J. Anticipation of distress after discontinuation of mechanical ventilation in the ICU at end of life. Intensive Care Medicine. 2008; 34(9): 1593-1599.

- Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, Haas Ce, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, Rushton CH, Kaufman DC. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Critical Care Medicine. 2008; 36(3): 953-63.

- Downar J, Delaney JW, Hawryluck L, Kenny L. Guideline for the withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. Intensive Care Medicine. 2016; 42(6): 1003-17.

- Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Hudson, OH. Available from: http://online.lexi.com. Accessed April 18, 2020.

- Thomas E. Safety and efficacy of atropine for salivary hypersecretion. Rho Chi Post. 2012; Nov 2(2): 8-9.

- Thellier D, Delannoy PY, Robineau O, Meybeck A, Bousekey N, Chiche A, Leroy O, Georges H. Comparison of terminal extubation and terminal weaning as mechanical ventilation withdrawal in ICU patients. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2017; 83(4): 375-82.

- Rubenfeld GD. Principles and practice of withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. Critical Care Clinics. 2004; 20(3): 435-51.

- Robert R, Le Gouge A, Kentish-Barnes N, Cottereau A, Giraudeau B, Adda M, et al. Terminal weaning or immediate extubation for withdrawing mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2017; 43(12): 1793-807.

- Campbell ML, Bizek Ks, Thill M. Patient responses during rapid terminal weaning from mechanical ventilation: a prospective study. Critical Care Medicine. 1999; 27(1): 73-7.

- Cheng KC, Hou CC, Huang HC. Intravenous injection of methylprednisone reduces the incidence of post-extubation stridor in intensive care patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2006; 34(5): 1345-50.

- Clark K, Connolly A, Clapham S, Quinsey K, Eager K, Currow DC. Physical symptoms at the time of dying was diagnosed: A consecutive cohort study to describe the prevalence and intensity of problems experienced by imminently dying palliative care patients by diagnosis and place of care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016; 19(12).

- Selby D, Chakraborty A, Lilien T, Stacey E, Zhang L, Myers J. Clinician accuracy when estimating survival duration: The role of patient’s performance status and time-based prognostic categories. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011; 42(2): 578-88.

- Morita T, Ichiki T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. A prospective study on the dying process in terminally ill cancer patients. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 1998; 15(4): 217-22.

- Counselman FL, Babu K, Edens MA, Gorgas DL, Hobgood C, et al. The 2016 model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017 Jun 1;52(6):846-9.

- O’Mahoney S, MchHugh M, Zallman L, Selweyn P. Ventilator withdrawal: procedures and outcomes: Report of a collaboration between critical care division and a palliative care service. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2003; 26(4): 954-61.

- Sedillot N, Holzapfel L, Jacquet-Francillon T, Tafaro N, Eskandanian A, et al. A five-step protocol for withholding and withdrawing of life support in an emergency department: an observational study. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2008; 15(3): 145-9.