Case Presentation

In the middle of a busy evening shift, EMS arrives with a 68-year-old woman complaining of abdominal pain.

The patient has a history of non-small cell lung cancer with known liver and adrenal metastases. She is currently on immunotherapy after having difficulty tolerating multiple lines of cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation due to side effects. She reports that the pain is most focal in the right upper quadrant, characterizing it as dull and gnawing, sometimes with sharp waves that last a few minutes.

The pain has been increasingly difficult to control using her home regimen of oxycodone extended release (ER) 30 mg twice daily (60 mg total), as well as oxycodone immediate release (IR) 15 mg Q4 hours PRN, which the patient had taken 4 times in the past 24 hours for breakthrough pain.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis shows an increase in the size of her liver and adrenal metastases, but no other acute abnormalities.

Looking at her home medication regimen, you start to feel overwhelmed.

“How can I get her pain under control safely?” you ask yourself.

Opioid Dose-Finding

Pain perception is a complex and dynamic process with multiple inputs including the pain stimulus itself, excitatory and inhibitory pathways in the spinal cord, changes in the number and type of opioid receptors expressed on various tissues and in the CNS, and our cognitive and emotional processing of pain.

In patients with advanced cancer, the combination of disease progression over time, as well as habituation to chronic opioids, often leads to the need to increase opioid dosing over the course of illness; this is called opioid tolerance. Patients with chronic opioid use and tolerance will generally require higher doses of opioids for rescue when they present to the ED with an acute pain crisis.

The following strategy can be used in the ED for those patients who present in acute pain while using chronic opioids. It is the most commonly recommended strategy among palliative care clinicians who manage cancer-related pain.

Step 1: Continue the patient’s long-acting opioid

Many patients on chronic opioids will be started on long-acting formulations, which minimize the peaks and valleys of effective analgesia frequently experienced by patients with usage of immediate release opioids. Oral immediate release opioids generally reach peak effect after approximately 1 hour, and then lose effectiveness after 3-4 hours, whereas long-acting formulations provide more stable analgesia for longer periods of time. Despite this, most patients will still have breakthrough pain on long-acting opioids and will require additional immediate release opioids PRN.

Oral long-acting agents are notated by acronyms such as controlled release (“CR”), sustained release (“SR”), and extended release (“XR/ER”); these can indicate slightly different chemical properties and rates of release, but are functionally interchangeable. The common suffix “-contin”, is short for “continuous” and indicates a continuous or controlled-release formulation (e.g., Oxycontin, MS Contin). Transdermal agents include fentanyl patches and, increasingly commonly, buprenorphine patches (Butrans). Other infrequently prescribed long-acting oral agents include hydromorphone (Exalgo, Palladone), oxymorphone (Opana ER), tramadol (ConZip), and tapentadol (Nucynta ER).Methadone and sublingual buprenorphine, both commonly used for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder (OUD), are also sometimes used as long-acting analgesics; however, their pharmacology is much more complex, and these patients should be discussed with an expert from palliative care, pain management, or addiction medicine. Hospice-enrolled patients also may occasionally present to the ED with home patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps that also have a basal infusion rate, which acts as the long-acting or continuous dose.

Step 2: Determine the patient’s daily opioid use prior to ED presentation

In order to treat your patient’s pain crisis, the total daily dose of opioid they have been taking must be calculated; this will allow you to more accurately and safely determine how much IV opioid the patient will require and can safely tolerate. You may need to speak with family or other caregivers to determine this information.

When calculating total daily opioid use, immediate release and controlled or extended release milligrams are counted the same. For example, a patient on 30 mg oxycodone CR twice daily in the past 24 hours (=60 mg), and who has taken oxycodone IR 15 mg four times in the past 24 hours (=60 mg), would be counted as having taken 120 mg oxycodone total. This total should then be converted into a reference standard: oral morphine equivalents (OME), sometimes also called morphine milligram equivalents (MME). Equivalence ratios of commonly used opioids include:

10 mg IV morphine = 30 mg PO morphine (OME)

20 mg PO oxycodone = 30 mg PO morphine (OME)

7.5 mg PO hydromorphone = 30 mg PO morphine (OME)

7.5 mg PO hydromorphone = 1.5 mg IV hydromorphone

Fentanyl patch @ 15 mcg/hr x 24 hours = 30 mg PO morphine (OME)

For these equivalences in table form, see Table 1.

TABLE 1

|

Drug |

Oral (PO) |

Parenteral (IV, IM) |

Transdermal |

|

Morphine |

30 mg = 30 OME (reference standard) |

10 mg |

- |

|

Hydromorphone |

7.5 mg |

1.5 mg |

- |

|

Oxycodone |

20 mg |

- (not available in U.S.) |

- |

|

Fentanyl |

- (rarely prescribed) |

150 mcg |

15 mcg/hr (24hr total = 30 OME) |

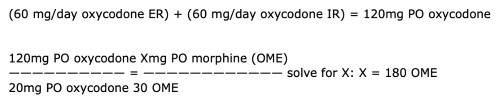

For this patient, the conversion of oxycodone IR and ER to OME is:

(60 mg/day oxycodone ER) + (60 mg/day oxycodone IR) = 120mg PO oxycodone

120mg PO oxycodone Xmg PO morphine (OME)

—————————— = ———————————— solve for X: X = 180 OME

20mg PO oxycodone 30 OME

Step 3: Convert 24 total OME into the IV opioid of choice

The most commonly used IV opioids in the United States are morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl. All three have advantages and disadvantages that are beyond the scope of this article. However, for some major considerations, see Table 2.

TABLE 2

|

IV Opioid |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Time to Peak Effect |

Duration of Action |

|

Morphine |

-Inexpensive -Easy conversion to multiple formulations -Least euphoria, likely lowest abuse potential |

-Causes dysphoria, nausea, other AEs more commonly -AVOID in renal disease, moderate or severe liver disease |

20-30 min |

2-4 hours |

|

Hydromorphone |

-Well tolerated, including in renal and liver disease -Commonly available -High receptor affinity (helpful if on MAT) |

-Causes euphoria, may have higher abuse potential |

15-20 min |

2-4 hours |

|

Fentanyl |

-Safest in severe renal or liver disease -Commonly available -Rapid onset/peak -High receptor affinity |

-Causes euphoria, may have higher abuse potential -Short duration of action may lead to inadequate analgesia |

7-10 min |

45-90 min |

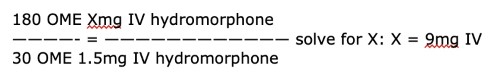

The patient tells you that she has had significant nausea with morphine in the past and would prefer to avoid it. You consider fentanyl, but you are worried about its short duration of action. To optimize tolerability as well as duration of action, you select hydromorphone IV:

180 OME Xmg IV hydromorphone

————- = ———————————— solve for X: X = 9mg IV

30 OME 1.5mg IV hydromorphone

Step 4: Give 10-20% of the daily total frequently until pain controlled

The patient’s 24-hour total equivalent dose is 9 mg hydromorphone IV, and a 10-20% range is 0.9-1.8 mg/dose. You elect to give 1 mg doses.

Twenty minutes after the initial dose, the patient reports mild pain relief and asks when she may receive more pain medication. As noted in Table 2, hydromorphone reaches peak effect at 15-20 minutes; thus your risk of dose stacking is very low if you repeat the dose approximately as often. The peak effect of a dose of an opioid includes the maximal analgesic effect and the maximal sedative/toxic effect, meaning that if the patient is not sedated 10 minutes after a dose of fentanyl, 20 minutes after a dose of hydromorphone, or 30 minutes after a dose of morphine, it is safe to give another dose. Additionally, sedation will reliably occur before clinically significant respiratory depression does, meaning that if the patient is awake, the likelihood of causing dangerous toxicity, specifically respiratory depression, is extremely low. This is the safety mechanism that underlies the use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps: As long as each incremental dose is unlikely to cause serious toxicity, the patient will fall asleep and stop pushing the PCA button before clinically significant respiratory depression occurs.

IV and immediate release oral opioids should be dosed Q2-4 hours PRN only AFTER the effective dose has been identified using the rapid re-dosing strategy outlined above.

Case Resolution

The patient is continued on her oxycodone CR 30 mg PO BID in the ED, and following 3 doses of 1 mg IV hydromorphone Q20 min, reports adequate pain control. Now that you have found an effective PRN dose, you continue the patient’s oxycodone ER 30 mg BID, and write for hydromorphone 3 mg IV Q4H PRN.

You speak with her oncologist, who thus far has been managing her outpatient pain medications, and review her care in the ED. The oncologist feels that this is a large enough increase in her PRN opioid needs that it would make sense to admit the patient to the oncology service for palliative care consultation and assistance with developing a new opioid regimen. You admit the patient to the oncology service and recommend to the admitting resident that they continue her oxycodone ER 30 mg BID, as well as hydromorphone 3 mg IV Q4H PRN.

Palliative care is consulted the following morning and further adjusts her oral long-acting and PRN opioid regimen. Thanks to your dose-finding efforts in the ED, the patient’s hospital length of stay is decreased by 1-2 days, and 36 hours later she is discharged home, with pain well controlled under her new regimen.