A 74-year-old male presents to the emergency department with dysphagia after accidentally swallowing a chicken bone five days ago.

He is only able to swallow small pieces of food and water. The patient reports a hoarse voice but denies fevers, difficulty breathing, or chest pain. He was evaluated by otolaryngology and underwent a laryngoscopy, but no bone was visualized. On physical examination, no foreign body is visualized and the oropharynx is clear. The patient’s lungs are clear in all fields without wheezing. Vitals are BP 166/109 mmHg; HR 68/minute and regular; RR 19/min and unlabored; T 97.3F; and SpO2 95% on room air.

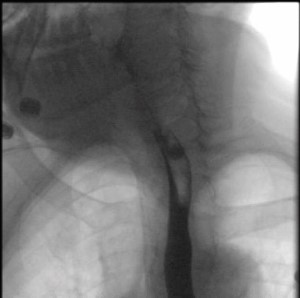

A CT of the neck shows a radiopaque foreign body in the upper to mid-esophagus at the level of C6-C7 vertebral bodies and the cricoid bone, extending anteriorly and down toward the right, with a contained perforation.

The patient is admitted for emergent surgery to remove the foreign body and repair the perforation. In the OR, an esophageal perforation is not found. Instead, the chicken bone is lodged transversely on top of the cricopharyngeal muscle and a small Zenker’s diverticulum. There is a small ulcer at the diverticulum, but no frank perforation or purulence. Chicken bone fragments are successfully removed.

A post-op esophagram shows a small anterolateral outpouching of the proximal esophagus likely reflecting a contained perforation versus Killian Jamieson diverticulum. No evidence of contrast extravasation outside of the outpouching is visualized.

The patient is discharged on amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, a soft food diet, and follow-up with thoracic surgery.

Discussion

This patient presented with dysphagia due to a foreign body ingestion five days prior. The main concern on arrival to the ED was esophageal perforation with resulting mediastinitis. Initial CT imaging demonstrated esophageal perforation; however, in the OR, the foreign body was found to be lodged in a Zenker’s diverticulum.

What appeared to be a contained perforation was, in actuality, a Zenker’s diverticulum. This diagnosis explains why this patient presented in a much more stable condition than one would expect for a true esophageal perforation.

Foreign body (FB) ingestion in the emergency department can have a variety of presentations, from benign to life-threatening. The majority of foreign bodies (80 – 90 %) pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously and without complications.1 Most commonly, a patient will present with an acute onset of dysphagia after ingestion of the FB. They may also have odynophagia, neck pain, sore throat, and, in more serious presentations, choking, stridor, dyspnea, fever, and/or crepitus.1,2

Esophageal perforation is a life-threatening condition caused by FB ingestion and can easily be missed. Therefore, suspicion for perforation should remain high until proven otherwise. This is a time-sensitive diagnosis and requires immediate surgery consultation.3,4 Even when identified and treated early, mortality from esophageal perforation is as high as 25%. If treatment is delayed more than two days from time of injury, mortality can reach 50-60%.5Unfortunately, there are no pathognomonic signs or symptoms of perforation; therefore, a thorough history and physical exam are imperative. If there is a delay in diagnosis, a patient can become critically ill and septic.

Initial recommended labs include CBC, CRP, and VBG. Initial imaging should include an X-ray of the neck, chest, and abdomen; however, be aware that if suspicion is high and X-ray results are negative, it is prudent to follow up with a CT scan for further evaluation.2 Case in point: Fish bone sensitivity on an X-ray is as low as 32%, while on CT it’s higher than 90%.1 Therefore, CT of the neck, chest, and abdomen is recommended if clinical suspicion remains high. CT can also detect and elucidate findings such as aspiration, free mediastinal or peritoneal air, or subcutaneous emphysema.1

If a patient has persistent esophageal symptoms, endoscopy should be performed within 24 hours. In the event of dangerous FB ingestion such as sharp objects, magnets, or batteries, endoscopy should be performed within 6 hours, but preferably within 2 hours if possible.2 In cases of esophageal perforation when the object cannot be retrieved by endoscopy, or if the FB is close to the aortic arch or other critical structures, immediate surgical intervention is required.

A stable patient who presents early with esophageal perforation can be observed closely. If non-operative treatment is initiated, the patient should be placed on broad-spectrum antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor.2

Conclusion

There is a broad differential for dysphagia, and there are a few key ED pearls to remember. First, a negative X-ray does not rule out the presence of a foreign body. Second, a CT should be performed if suspicion for a FB is high, regardless of the X-ray results. Most importantly, the emergency physician must always consider esophageal perforation and assess for the presence of sharp objects, magnets, and batteries. These patients, in particular, will need intervention within a matter of hours.

Mechanical and Neuromuscular Dysphagia

Two Considerations When no Foreign Body is Found

Although foreign body (FB) ingestion is an important etiology for acute dysphagia, when no FB is identified, there are two main etiologic categories to consider: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical causes account for the majority of cases and include malignancy, esophageal stricture, scleroderma, a Schatzki ring (esophageal web), thyroid enlargement, Zenker's diverticulum, and foreign body ingestion. Neuromuscular causes include CVA, achalasia, medication side effects, esophageal spasm degenerative diseases, ALS, MS, muscular dystrophy, and myasthenia gravis.3

Mechanical dysphagia usually presents with difficulty swallowing solids only.4 For example, a schatzki ring often presents with food bolus impaction and regurgitation, as it is a mucosal structure that impairs passage through the gastroesophageal junction. This type of mechanical dysphagia is typically a non-progressive dysphagia and presents more intermittently. However, more concerning diagnoses, such as esophageal stricture or carcinoma, will present in a more progressive manner as the obstruction worsens over time. In the case of mechanical dysphagia, evaluation with endoscopy can be used both to diagnose and sometimes to treat.4

Neuromuscular dysphagia usually presents with difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids.4 Unless a patient presents at a very late stage, neuromuscular dysphagia workup is more appropriate in the outpatient setting. This is usually a progressive presentation over time and, in most cases, is not immediately life threatening, except in the setting of a cerebrovascular accident. A more acute onset of dysphagia involving both solids and liquids should raise your suspicion for CVA and needs to be ruled out in the ED. This is the most common cause of oropharyngeal dysphagia.3 Once a CVA is ruled out, the patient can be referred to GI or ENT for further evaluation. If a diagnosis cannot be made with endoscopy or barium swallow, the next modality for diagnosis is manometry. Manometry can be used to assess esophageal pressures and sphincter tone to identify esophageal motility disorders (EMD).4 Treatment for EMD varies based on the diagnosis and is not typically managed in the emergency department.

References

- Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, et al. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48(5):489-496. doi:10.1055/s-0042-100456

- Chirica M, Kelly MD, Siboni S, et al. Esophageal emergencies: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:26. Published 2019 May 31. doi:10.1186/s13017-019-0245-2

- Spieker MR. Evaluating dysphagia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(12):3639-3648.

- Chilukuri P, Odufalu F, Hachem C. Dysphagia. Mo Med. 2018 May-Jun;115(3):206-210. PMID: 30228723; PMCID: PMC6140149.

- Wei CJ, Levenson RB, Lee KS. Diagnostic Utility of CT and Fluoroscopic Esophagography for Suspected Esophageal Perforation in the Emergency Department. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(3):631-638. doi:10.2214/AJR.19.22166