Surfing is a widely popular water sport, with an estimated 35 million surfers worldwide.1 Numerous surf competitions are held each year, showcasing the sport’s most popular athletes. The sport even made its Olympic debut at the 2020 Tokyo Games and has been approved by the International Olympic Committee for future Olympics. Surfers can be found from the warm tropical waters of Hawaii to the frigid waters of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia and everywhere in between.

Surfing, like most sports, does not come without risk. With its ever-growing popularity, considerations of potential injury and safety in the water should be recognized by the emergency physician.

“Surf medicine” refers to the field of medicine focused on the trauma and diseases that affect surfers.2 There are many perspectives within the surfing community about the potential hazards of time spent in the water; these perspectives, along with potential hazards, vary with location and setting. Those who manage these conditions range from “barefoot doctors” — surfers with the training and skills to respond to injuries in remote locations without immediate access to medical facilities — to medical professionals in the emergency department.2

Knowledge and awareness about the breadth of potential injuries that may present to an ED is essential to preparedness among care providers in surfing communities around the globe.

Causes for Concern

Popular surf websites provide insight into what surfers think about before entering the water. The number one most referenced concern is marine life, specifically sharks and the fear of an unprovoked attack.4,5

In 2021, there were 107 reported shark attacks worldwide, 22 of which occurred while surfing, and two of which were fatal. An analysis of global shark attack data from 1900 to 2014 showed that the highest proportion of attacks occurred while swimming (30.5%), followed by surfing (22.5%).13

While this concern regarding shark attacks is certainly valid, it may not reflect the most common hazards specific to riding a wave. Two separate studies have found that less than 3% of injuries are caused by marine life, and the most common marine life injuries are from jellyfish, sea urchins, and stingrays.7 Furthermore, compared to other mechanisms of surf injuries such as lacerations and ligamentous sprains, shark attacks are a disproportionate concern when considering risk level.

The second-highest cited concern in the surfing community is in regard to waves and rip currents — the fear of drowning and osseous injuries from impact. Wave size varies dramatically by location, from the 50-foot waves of Nazaré, Portugal, to the average 3- to 4-foot waves seen in San Diego.8-9 The difference in wave size will influence the type of injury and its severity. As mentioned by Nathansan et al, tube riding has a drastically different level of risk than open-face riding due to the changes in energy and force of the wave.7

Additional concerns include wounds from rocks and coral; sunburns; dehydration; collisions with other surfers; and injuries stemming from the leashes that connect surfers with their boards, as these can become tangled around limbs.4,5

Common Injuries

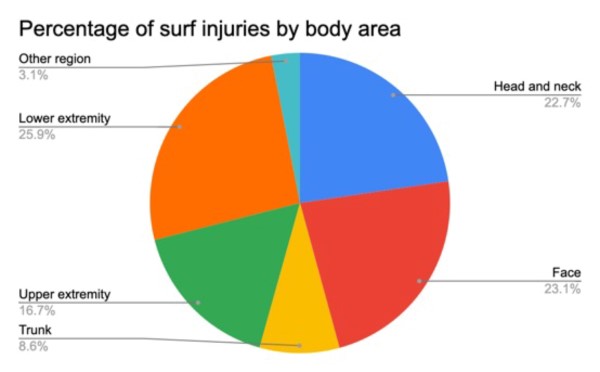

A literature review of surfing injuries provides insight into the epidemiology of injury. Contrary to popular perceptions, marine wildlife attacks and drowning do not make up the majority of surf injuries.7 The most common cause of trauma during surfing is from the surfboard itself.

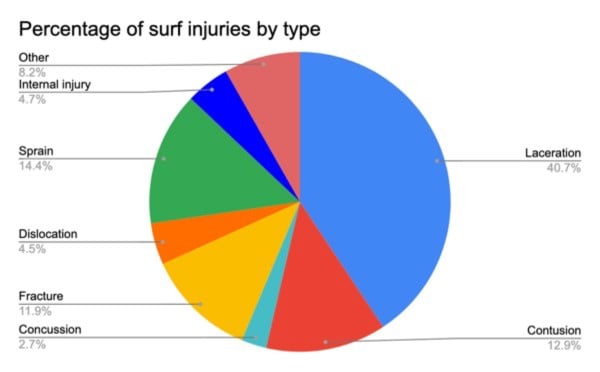

Lacerations account for the largest portion of surf injuries — largely to the head and neck, with the scalp and face being particularly vulnerable.10 These lacerations generally result from collisions with the rider’s own board, coral reefs, and rocks.7

One particular study found that the majority of head injuries suffered were mild traumatic brain injuries (concussions), and less commonly tympanic membrane rupture and fractures involving the jaw, skull, and teeth.10

Severe neck injuries include cervical spine fractures.

It is important to note that the use of protective head gear is not yet commonplace in surfing, even considering the demonstrated risk.11 Injuries to the head and neck — such as brain injury, cranial fractures, and vertebral fractures — require more extensive treatment, including hospital admission and surgical intervention. This demonstrates a key area where immediate recognition and intervention, such as in the ED, can have a large impact on morbidity. This also presents an opportunity where a shift among surf culture toward protective headgear could reduce the incidence of severe head injuries.

Trauma from the force of the wave itself includes ruptured tympanic membranes, near drownings, shoulder dislocations, and sprains to the lower limbs from bodily force during turns.10 Many of these injuries are treatable in an ED setting and do not result in inpatient admission.12

In EDs where surfers are a common demographic, an awareness of potential injuries and their possible sequelae can help determine the level of care needed.

Interestingly, the more experienced or the older a surfer is, the higher the risk of significant injury.10 Additionally, the frequency of surf injuries requiring hospital admission is higher for older patients, an important consideration in determining a patient’s disposition.14 These factors necessitate a need for risk stratification based on patient demographic, not dissimilar to the triage and management of other sports injuries.

Significance for the EM Physician

As the popularity of surfing grows, the incidence of surf injuries — both minor and traumatic — will increase accordingly. Surfers will present to the ED with a wide range of pathologies, from head wounds to ligament sprains.

An understanding of the mechanisms of these injuries and location-specific hazards is important. This will allow for increased alertness of, and preparedness for, possible life-threatening presentations. In emergency departments likely to see surf-injury patients, education could be incorporated into simulations and didactic sessions focused on sports injuries.

Emergency physicians are masters at taking care of anything and everything that comes through the door, and continued exploration of surf medicine increases this diversity.

References

- SurferToday.com. How many surfers are there in the world? Surfertoday. https://www.surfertoday.com/surfing/how-many-surfers-are-there-in-the-world#:~:text=According%20to%20well%2Destablished%20and,17%20million%20and%2035%20million. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- Our story. Surfers Medical Association Site Wide Activity RSS. https://www.surfersmedicalassociation.org/about/. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- McArthur K, Jorgensen D, Climstein M, Furness J. Epidemiology of acute injuries in surfing: Type, location, mechanism, severity, and incidence: A systematic review. Sports. 2020;8(2):25. doi:10.3390/sports8020025

- The risks of surfing. Surfing Waves. https://surfing-waves.com/surfing-dangers.htm. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- Webmaster. Surfing dangers: Staying safe in Open water. San Diego Surf School. https://www.sandiegosurfingschool.com/blogs/surfing/surfing-dangers-staying-safe-in-open-water/. Published March 26, 2022. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- Global Shark Attack - World. public. https://public.opendatasoft.com/explore/dataset/global-shark-attack/table/?disjunctive.country&disjunctive.area&disjunctive.activity&refine.date=2021. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- Nathanson A, Haynes P, Galanis D. Surfing injuries. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2002;20(3):155-160. doi:10.1053/ajem.2002.32650

- Monster waves of nazaré. NASA. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/149486/monster-waves-of-nazare. Accessed October 2, 2022.

- Wave size in San Diego - how big are they? Go Surfing SD! https://gosurfingsandiego.com/wave-size-san-diego/. Published April 3, 2022. Accessed October 2, 2022.

- Hay CSM, Barton S, Sulkin T. Recreational surfing injuries in Cornwall, United Kingdom. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2009;20(4):335-338. doi:10.1580/1080-6032-020.004.0335

- Taylor DM, Bennett D, Carter M, Garewal D, Finch C. Perceptions of surfboard riders regarding the need for protective headgear. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16(2):75-80. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2005)16[75:POSRRT]2.0.CO;2

- Taylor DMD, Bennett D, Carter M, Garewal D, Finch CF. Acute injury and chronic disability resulting from surfboard riding. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2004;7(4):429-437. doi:10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80260-3

- Ricci JA, Vargas CR, Singhal D, Lee BT. Shark attack-related injuries: Epidemiology and implications for plastic surgeons. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(1):108-114. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2015.08.029

- Klick C, Jones CM, Adler D. Surfing USA: an epidemiological study of surfing injuries presenting to US EDs 2002 to 2013. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1491-1496. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.05.008