Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infants and children.

Although traditional teaching revolves around the “classic triad” of paroxysmal abdominal pain, bloody stool, and vomiting, the presenting symptoms often vary, which can make intussusception a diagnostic challenge.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy, fully vaccinated 2.5-month-old female born at full gestation presented to the emergency department with hematochezia and bilious emesis. She had presented four days prior to the ED with fussiness. At that time, she was initially inconsolable, but had improved with resolution of her fussiness by the time of discharge. Since discharge, her fussiness had worsened, and she became increasingly lethargic. She was noted to have had decreased oral intake and had not tolerated a full feed in three days.

On the day of presentation, she had multiple episodes of “ninja turtle emesis” as well as multiple episodes of bright red blood per rectum. The child had not had fevers, recent travel, antibiotic exposure, constipation, or diarrhea. Triage vitals were within normal ranges. On exam, she was pale and lethargic with intermittent episodes of crying. She had dry mucous membranes, a distended abdomen without any palpable masses, and had a soiled diaper with blood but no stool.

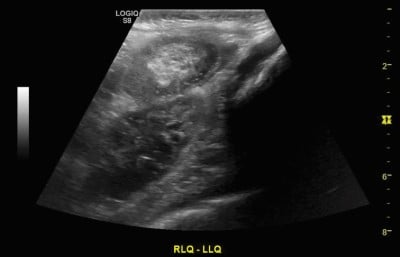

Given the concern for intestinal obstruction and her overall ill appearance, medical resuscitation efforts were started immediately and calls to transfer to the nearest pediatric acute care hospital were initiated, including notifying the pediatric surgical team. After an IV was established, a 20 mL/kg bolus of crystalloid was administered and labs were sent, which were unremarkable. A nasogastric (NG) tube was ordered, but the appropriate size was unavailable immediately. Plain radiographs of the abdomen were obtained and were notable for dilated loops of bowel without evidence of free air. The transfer team arrived before abdominal ultrasound could be obtained. Upon arrival to the closest children’s hospital, a bedside point-of-care ultrasound identified an intussuscepted bowel in the pattern of a target sign as distal as the left upper-quadrant. The on-call radiologist confirmed ileocolic intussusception on formal abdominal ultrasound.

Image 1: Abdominal X-ray demonstrating multiple dilated loops of bowel

Image 2: Abdominal ultrasound showing a “target” sign most consistent with an ileocolic intussusception

Image 3: “Pseudokidney” sign on abdominal ultrasound also diagnostic of an ileocolic intussusception

Discussion

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infants and children between the ages of 3 months to 6 years but typically occurs between 6 to 36 months.1 It can, however, occur in older children and, rarely, in adults. It is a life-threatening illness resulting from one part of the intestine telescoping into another, causing bowel obstruction that can lead to ischemia and, ultimately, bowel necrosis and peritonitis. In most cases, the cause is unknown, but some patients have an identified lead point such as a polyp or tumor. Viral infections may also be responsible for some cases. There is a slight male predominance for the illness. With early diagnosis, appropriate fluid resuscitation, and immediate therapy, the mortality rate in children is less than 1%. However, if left untreated, the condition is often fatal.2

Because of the patient’s age, we considered alternative causes of her presentation, including other obstructive processes (i.e., malrotation, volvulus, Hirschsprung’s disease, and necrotizing enterocolitis). Pyloric stenosis was briefly considered, but given that symptoms typically present within the first 3-6 weeks of life and usually without stool changes, this diagnosis was unlikely.

The classic triad that is often described for intussusception includes colicky abdominal pain, currant-jelly stools, and vomiting or a palpable sausage-like mass. All three symptoms, though, are present in fewer than 25% of cases.3

Pain in intussusception is colicky, severe, and intermittent. Initially, vomiting is nonbilious but in later stages becomes bilious. Parents may report stools that look like currant jelly; these stools are a mixture of mucus, sloughed mucosa, and blood. Diarrhea can be an early sign of intussusception. Lethargy may be the sole presenting symptom in young infants and can make the diagnosis challenging, thus requiring one to have a high index of clinical suspicion.

The exam can be challenging, and the most frequent presentation is a child with intermittent episodes of fussiness during which they are not consolable. Patients are often seen drawing their legs up to the abdomen with periods of relief in between attacks. There may be a palpable right hypochondrium sausage-shaped mass, but this is a rare finding, and its absence does not exclude the diagnosis. Abdominal guarding may be present during acute episodes of intussusception. Further adding to difficulty in evaluation is that intussusception may spontaneously reduce only to recur soon afterwards. Consider the diagnosis in the young child who has intermittent episodes of extreme irritability. Be aware that a child with a later presentation may present with altered mental status. In addition, assessment of hydration status is critical in these patients.

Laboratory investigation is usually non-specific; with persistent vomiting, dehydration and electrolyte derangements may be present. If present, leukocytosis or acidosis may suggest bowel injury, necrosis, or perforation. Plain abdominal radiography may show signs of intestinal obstruction and free air if complicated by perforated viscus. However, ultrasonographic imaging is the diagnostic modality of choice and will demonstrate the “target” and “pseudokidney” signs.4 Point-of-care ultrasound has shown very high sensitivity in identifying acute intussusception and should be considered if available.5

Initial Management

Vascular access, fluid resuscitation, NG tube placement for decompression, and prompt surgical consultation should take place concurrently with radiologic consultation. Nonoperative reduction is first-line therapy. A water soluble or an air contrast enema will definitively diagnose intussusception and is frequently curative.6

Surgery may be indicated when nonoperative reduction is incomplete or the patient has a perforation or peritonitis. Perforation is a risk of reduction by enema, and surgical specialists are often at bedside or immediately available for operative intervention if this occurs.

Patients generally have good outcomes, and recent data has shown that most patients can be safely discharged from the ED following reduction after a brief period of observation. There is no evidence for a difference in the rate of complications between patients who are observed in the ED versus admitted following enema reduction of an ileocolic intussusception.

Though the rate of recurrence is low, parents should be educated on recurrent symptoms and the importance of returning to the ED, while physicians should assess the family’s local resources and ability to return to the ED if needed. When assessing which patients may be better suited for admission, those who are clinically dehydrated, unstable, or had a complicated reduction should be given greater consideration for hospital admission and serial reassessment.7,8

Case Conclusion

Pediatric surgery evaluated the patient, and she was taken urgently for nonoperative reduction with an air contrast enema performed by the pediatric radiologist. The reduction was noted to be difficult due to the degree of bowel involved, but it was ultimately successful. Following reduction, the patient was admitted for inpatient observation without further complication and discharged on hospital day 2. On follow-up with her pediatrician, the patient has been doing well, tolerating feedings, and has made expected growth for her age.

References

- Waseem M, Rosenberg HK. Intussusception. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2008;24(11):793-800. doi:10.1097/pec.0b013e31818c2a3e

- Gluckman S, Karpelowsky J, Webster AC, McGee RG. Management for intussusception in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online June 1, 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006476.pub3

- Abdulhai S, Ponsky T. Intussusception in Infants and Children. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Published online 2021:549-554.e1. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-67293-1.00051-7

- Daneman A, Navarro O. Intussusception. Pediatric Radiology. 2003;33(2):79-85. doi:10.1007/s00247-002-0832-2

- Lin-Martore M, Kornblith AE, Kohn MA, Gottlieb M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Intussusception in Children Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. West J Emerg Med. 2020 Jul 2;21(4):1008-1016. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.46241.

- Bruce J, Huh YS, Cooney DR, Karp MP, Allen JE, Jewett TC. Intussusception: evolution of current management. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1987;6(5):663-674.

- Kelley-Quon LI, Arthur LG, Williams RF, Goldin AB, St Peter SD, Beres AL, Hu YY, Renaud EJ, Ricca R, Slidell MB, Taylor A, Smith CA, Miniati D, Sola JE, Valusek P, Berman L, Raval MV, Gosain A, Dellinger MB, Sømme S, Downard CD, McAteer JP, Kawaguchi A. Management of intussusception in children: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2021 Mar;56(3):587-596. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.09.055.

- Raval MV, Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Kurtovic KJ, Dietrich A, Bates DG, Rangel SJ, Moss RL, Kenney BD. Improving Quality and Efficiency for Intussusception Management After Successful Enema Reduction. Pediatrics. 2015 Nov;136(5):e1345-52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3122.