Ch. 12. Scope Trials and Tribulations

Miltiadis Kerdemelidis, MD; Stefania Markou, DO, MPH; Andrew Little, DO

Chapter 12. Scope Trials and Tribulations

Recorded by Amanda Irish, MD, MPH | Prisma Health

As the field of emergency medicine continues to grow and expand, so does the role that non-physician providers (NPPs) wish to take in the specialty. Understanding how we got to where we are plays a vital role in knowing where to go from here.

Patients deserve to know exactly who is providing their care, and that the highest quality care in the emergency department is overseen by an ABEM-certified physician.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

As they require less time to train and are cheaper to employ, employers have moved to the use of NPPs, and this move is leading to less safe care for patients and fewer jobs for board certified/board eligible emergency physicians.1,2 Of all the threats to EM, scope creep and increasing number of NPPs is one that all EM doctors should be worried about.

How We Got to This Point

The United States continues to face an imbalance in supply and demand for physicians. Filling this void, the number of non-physician providers (NPP) entering the health workforce and the ED specifically has increased substantially in the past few decades.3 Nationwide, there were an estimated 355,000 licensed nurse practitioners (NPs) as of 2022, representing a 9% increase in a single year.4,5 Physician assistants (PAs), meanwhile, voted in 2021 to change their name to “physician associates”6 as they welcomed a record number of newly certified PAs to their ranks, surging to a 2021 total of 158,470 certified PAs in the U.S. – a 5-year increase of nearly 30%.7 In this same time frame, as NPP numbers have risen, attrition of emergency physicians picked up speed, outpacing forecasts and topping a 5% attrition rate, even as fewer medical students expressed an interest in the specialty.8,9

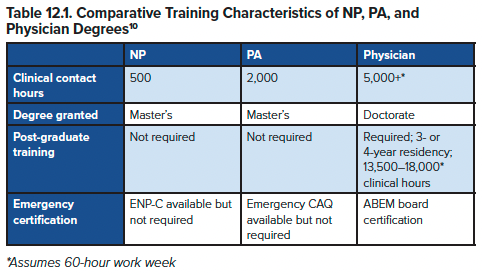

The level of practice autonomy granted to NPPs is dictated by state law and hospital bylaws, and although NPs and PAs typically have similar levels of autonomy in EDs, they take different training routes, as seen in Table 12.1.10

The PA Education Association (PAEA) reported 351 PA programs in the 2022- 2023 application cycle,12 and of those, 300 are accredited by the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA).13 The Society for EM PAs (SEMPA) has created postgraduate training standards as a framework that new and existing EM PA postgraduate programs can use to improve or create EM PA postgraduate programs.10

PA postgraduate programs range in length from 1-2 years, with most lasting 18 months. Many PA postgraduate programs are housed in institutions with EM residencies. Many of those integrate their didactic curricula, so PAs join EM resident educational conferences, journal clubs, clinical rotations, simulation, and research requirements.15 When a limited number of procedures are available in a given training environment, increasing the number of trainees by including NPPs may decrease the procedures available for EM residents to perform as part of their training. In 2022, 277 EM residency programs recruited nearly 3,000 newly minted emergency medicine residency-trained physicians a year; the number of postgraduate training programs available to NPs and PAs is much smaller.9 However, with NPP specialty organizations attempting to standardize training, there continues to be overall growth in the numbers of NP and PA postgraduate programs and a push toward completing advanced training after graduating from NP/PA school.

The proportion of ED patients seen by an NPP has substantially increased over time. According to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, NPPs saw nearly 25% of all ED patients in 2020 (10.1% seen by NPs, 13.4% seen by PAs)16 – up from just over 20% of ED patients seen by NPPs in 201517 and only 5.5% in 1997.

NPPs see a range of acuity levels but often staff high-volume, fast-track, or express care sections within EDs. Compared to physicians, NPPs often see lower acuity patients, with only 11% of patients seen by NPPs in the highest triage category.18,19

In addition to caring for a large and varied level of ED patients, NPPs have been working in more EDs and working more hours. According to surveys from the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance, the percent of EDs utilizing NPPs ballooned from 23% in 2010 to 62% in 2016. Moreover, NPPs are working more of the total hours available. In 2010, NPPs worked 53% of physician staffing hours; by 2016, this number had risen to 64%.11 According to the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, “between 2010 and 2025, the supply of non-primary care [NPP] FTEs is expected to grow by 141% overall, with growth anticipated in every field where these providers are represented.”20

EM physicians perceive a difference between NPs and PAs: a poll revealed that EM physicians believe NPs tend to use more resources as compared to PAs, and that NPPs use more resources than physicians when seeing patients with similar emergency severity index levels.21 In addition, there was more interest in hiring younger, less-trained PAs as compared to NPs, with a possible reason cited as the clinical education for PAs was thought to be stronger than NPs.21 Although the data is obscured by different state laws regarding NPPs, it may partly explain differences in levels of physician oversight for NPPs. In fact, from the NHAMCS respondents, only half of the patients who received care from a PA during an encounter also saw a physician, as compared to two-thirds of those who received care from a NP.16

Current State of the Issue

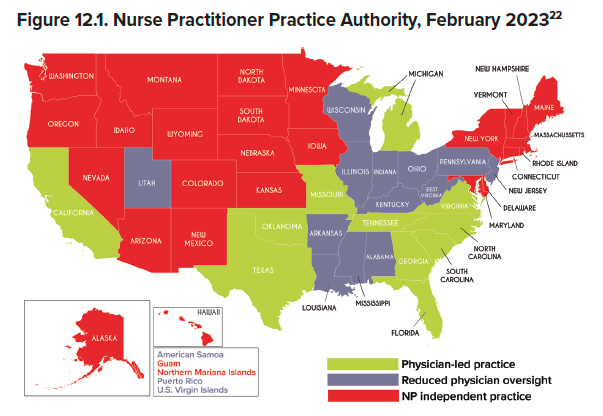

As the use of NPPs balloons in EDs, NPPs seek to increase their scope of practice – and it’s working.22 Notably, New York, Massachusetts, Delaware, and Kansas all granted NPs full practice authority within the past 5 years (see Figure).

“Scope of practice” is the term describing the regulatory means of guiding the activities different medical professionals are able to perform and the independence afforded to their practice. State legislatures govern this, and they are influenced by Congress, CMS, and the Federal Trade Commission.

With differing scope of practice laws in each state, health professionals are subjected to various rules. Some NPPs practice alongside a physician, while others practice independently. Some states have enacted legislation allowing for NPs to practice with full autonomy. The degree of independence of NPP practice thus varies significantly from state-to-state and from ED-to-ED.

Oversight of PAs may mandate a physician be physically present onsite, or available through phone/videoconferencing, or simply review/sign PA medical documentation. Even further complicating this, some states allow PA oversight to be dictated at the institutional level. These laws affect NPP and physician liability as well as overall medical workforce coverage. For example, states with fewer NPP restrictions tend to have higher numbers of NPPs practicing in comparison to physicians.

NPP advocacy groups have lobbied to expand NPP coverage in the ED, focusing on increased independence from physicians. Some NPP groups have an explicitly stated goal of full practice autonomy. With continued physician shortages, gaps in coverage exist and NPPs position themselves as a means to fill the gap and curb health care spending. This has led to increased autonomy in states with the largest gaps in coverage.

In response, the AMA has created the Scope of Practice Partnership (SOPP).23 The SOPP, with EM representation provided by ACEP, tackles scope creep via public and legislative advocacy.

Truth in Advertising

As NPP scope expands, so do concerns of misrepresentation of credentials. Patients are confused by the expanding ability of NPPs to prescribe treatments and perform procedures, and some NPPs use the title of “doctor” to represent doctorates other than MD and DO. In efforts to increase transparency, the AMA

launched the Truth in Advertising campaign.24 In building this initiative, the AMA queried patients to determine their understanding of the distinction between medical doctors and other doctorates. They discovered 45% of patients do not find it easy to tell licensed medical doctors apart from others identifying themselves as “doctors” in the health care setting; 39% believe a doctor of nursing practice is a medical doctor.24

The model legislation developed by this campaign:

- Requires all health care professionals to clearly and accurately identify themselves in all publications, advertisements, and other communications.

- Requires all health care professionals to wear, during patient encounters, a name tag that clearly identifies the type of license they hold.

- Prohibits advertisements or websites advertising health care services from including deceptive or misleading information.

One of the most frequently repeated claims in seeking greater autonomy for NPPs is that this autonomy will improve access to care for patients. However, studies and anecdotal reports are largely not supporting those claims, as NPP training and jobs continue to grow in areas with strong access to health care, while still leaving large swaths of less-populated regions scrambling for care.25 While advocates of NPP autonomy may argue that use of NPPs can lead to cost savings, data demonstrates that NPPs tend to order more tests in comparison to physicians,26 which increases total costs of care.

Moving Forward

According to the ACEP Code of Ethics for Emergency Physicians, emergency physicians have an ethical duty to promote population health through advocacy and to participate in “efforts to educate others about the potential of well-designed laws, programs, and policies to improve the overall health and safety of the public.”27 Physician advocacy can range from working toward state health care reform to advising a local school board. Advocacy activities might include attending a physicians’ day at the state capitol, testifying before a committee, or corresponding and meeting one-on-one with an elected official.

In the setting of scope creep, however, all emergency physicians must be mindful of the line between advocating for your patients and your specialty and denigrating other members of the health care team. The message is not that NPPs are “bad” and physicians are “good;” it is that patients deserve to know exactly who is providing their care, and that the highest quality care in the emergency department is overseen by an ABEM-certified physician.

TAKEAWAYS

- As the increase in NPPs continues among emergency medicine, every EM physician must know the laws governing the scope of practice of NPPs in their state.

- EM physicians need to advocate for the continued importance of physicians as health care team leaders in emergency medicine.

- PAs and NPs have substantially fewer hours of training and less standardized training (particularly in the case of NPs) than physicians.

- The drive to decrease health care costs by payers and increase compensation for leaders of provider groups has led to the increasing use of NPs and PAs rather than emergency physicians in the provision of emergency care.

- Scope of practice is a dynamic issue that requires ongoing advocacy at the state level, in collaboration with other specialties, and recognizing the differences between types of nonphysicians.

- EM physicians need to prioritize working with government representatives and NPP organizations to promote a culture of transparency in providing patients accurate information about provider’s credentials and roles.

References

- Kelman B, Farmer B. ERs staffed by private equity firms aim to cut costs by hiring fewer doctors. NPR. Feb. 11, 2023.

- Chan Jr. DC, Chen Y. The productivity of professions: Evidence from the emergency department. National Bureau of Economic Research. October 2022.

- Hall M, Burns K, Carius M, Erickson M, Hall J, Venkatesh A. State of the National Emergency Department Workforce: Who Provides Care Where? Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(3):302-307.

- Severson A. Nurse practitioners on the rise. Working Nurse. May 5, 2022.

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP Fact Sheet. https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet.

- Update on board certification and title change terminology. Dec. 1, 2022.

- 2021 statistical profile of certified PAs. December 2022.

- Gettel CJ, Courtney DM, Janke AT, Rothenberg C, Mills AM, Sun W, Venkatesh AK. The 2013 to 2019 emergency medicine workforce: Clinician entry and attrition across the US geography. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80(3):2260-271.

- Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022.

- Chekijian SA, Elia TR, Horton JL, Baccari BM, Temin ES. A review of interprofessional variation in education: Challenges and considerations in the growth of advanced practice providers in emergency medicine. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(2):e10469.

- Augustine JJ. More advanced practice providers working in emergency departments. ACEP Now. Sept. 19, 2017.

- PA Education Association. 2022-2023 Application Cycle Programs. 2022.

- Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. Accredited programs. 2022.

- Society of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants. Emergency Medicine Physician Assistant Postgraduate Training Program Standards, Version 1.0. Aug. 6, 2015.

- Kraus CK. EM physician assistant Terry Carlisle recalls long career, discusses future of specialty. ACEP Now. Sept. 20, 2017.

- Cairns C, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2020 emergency department summary tables. 2020.

- Rui P, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2015.

- Mafi JN, Chen A, Guo R, et al. US emergency care patterns among nurse practitioners and physician assistants compared with physicians: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e055138.

- Menchine MD, Wiechmann W, Rudkin S. Trends in midlevel provider utilization in emergency departments from 1997 to 2006. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(10):963-969.

- National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Projecting the supply of non-primary care specialty and subspecialty clinicians: 2010-2025. Health Resources and Services Administration.

- Phillips AW. Emergency physician evaluation of PA and NP practice patterns. JAAPA. 2018;31(5):38-43.

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. State Practice Environment Interactive Map. Accessed February 2023.

- American Medical Association. Scope of practice key tools & resources. Updated Jan. 5, 2023.

- American Medical Association. Truth in Advertising initiative. 2018.

- Robeznieks A. Amid doctor shortage, NPs and PAs seemed like a fix. Data’s in: Nope. AMA. March 17, 2022.

- Christensen EW, Liu CM, Duszak Jr. R, et al. Association of state share of nonphysician practitioners with diagnostic imaging ordering among emergency department visits for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241297.

- Code of Ethics for Emergency Physicians. Updated 2017.