Ch. 10. "New" Methods to Control Costs: Quality and Data

Evelyn Huang, MD; Jacob Altholz, MD; Jesse Schafer, MD

Chapter 10. "New" Methods to Control Costs: Quality and Data

Recorded by Evelyn Huang, MD | Northwestern University

Reimbursement structures have become increasingly complex in medicine. In an effort to contain costs while improving care, the current trend is tying payment to “quality” as defined by CMS, while shifting the measurement and reporting of quality metrics to physicians and institutions. Understanding how these metrics are built, implemented, and managed is vital to understanding the financial incentives that underpin health care.

Emergency physicians can offer insight into metrics that are important to our practice and advocate against metrics that impair, impose unintended consequences, or do not otherwise reflect the standard of care.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

Over the past two decades, CMS has taken a proactive stance to control health care costs by using quality measures as a core component.1-3 Physicians are meant to report on how often they meet certain predetermined quality measures, and this translates to level of reimbursement.1-5 But who sets these quality measures and do these quality measures truly reflect high-quality or high-value care?6 Emergency medicine straddles both the outpatient and inpatient setting so quality measures aimed at addressing health outcomes in those settings do not easily translate to emergency care.7 Sociodemographic factors outside of the control of emergency physicians influence patient outcomes and can affect how well the emergency physician can meet certain quality measures.7-11 Additionally, patients often have limited choice in deciding where and how they receive their care in an emergency. We, as physicians, are morally and legally obligated to treat those who seek our care, regardless of a patient’s ability to pay. Our profession’s adherence to this ethical principle historically strains our ability to contain costs, especially since the passage of EMTALA in 1986. EMTALA enshrines in law the requirement that emergency departments provide a medical screening exam (MSE) to anyone and appropriately treat and stabilize any emergency condition.12 This is often done with limited information, particularly for patients with complex care needs.

Within that framework, quality metrics were designed to increase the value of health care per dollar spent. The general idea is to encourage physicians to meet certain “optimal” criteria across different domains related to the processes and outcomes of health care through financial incentives. Physicians aligning with metrics receive higher reimbursement compared to those who score lower on the metrics. However, not all quality metrics achieve this goal, and an intensive focus on metrics may alter an emergency physician’s motivations in other ways, creating unintended consequences in the health care system.

Just over two decades ago, two retrospective studies linked early antibiotic administration with decreased mortality and length of stay in patients with community-acquired pneumonia.13,14 These studies eventually became the justification behind the creation of a quality metric titled PN-5b. The metric stipulated antibiotic administration within 4 hours of arrival for pneumonia patients. Subsequent research, however, did not reveal any improvement in mortality, need for ICU level care or intubation, or length of stay for those patients receiving early antibiotics compared to those who did not.15 Moreover, many physicians argued that meeting this metric was not feasible due to inherent systemic limitations with throughput in emergency care.16 Despite this, definite changes were made in emergency departments across the country with the intent of meeting the metrics and increasing reimbursement.17 Quality metrics had introduced an external motivation to alter the usual care provided to patients despite poor evidence that it would actually improve care for patients.

The story of PN-5b illustrates the need for rigorous certification of any quality metric, as well as ongoing assessment in light of the latest research findings. If the intent of a specific metric is to improve outcomes and/or save on costs, it must be thoroughly vetted because of its ability to alter clinical practice. Linking quality to financial pressures may also have serious implications for facilities in serving different socioeconomic groups. For example, a county safety net hospital may be expected to have a larger burden of uncompensated care, when compared to a private hospital. Both systems are subject to payment adjustments, whether positive or negative, based on how each hospital meets certain quality metrics and regardless of external forces that influence the quality of care delivered such as boarding, throughput, access to follow up, and community resources. Ideally care would be solely evidence-based, but in a world of limited resources, metrics tied to reimbursement demonstrably change the way physicians practice medicine for better or worse.

How We Got to This Point

Traditionally, reimbursement has been centered entirely around “fee-for-service” models (ie, payment was based on the actual services a physician delivered). For the patient or the payer, the more services received, the more costs accrued during a visit. The corollary holds true for the physician: the more services provided, the more reimbursement received. The fee-for-service model can incentivize unnecessary testing and procedures, especially for well compensated services. This does not necessarily correlate with “ideal” or “value-based” care. Fee-for-service is felt, therefore, to be a driver of increased health care costs.18

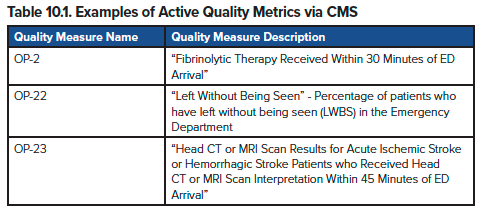

While the United States largely remains in a fee-for-service model, changes in the last twenty years have aimed at tying quality of care to payments. Quality measures for Medicare are developed through CMS in cooperation with organizations, such as National Quality Forum (NQF), medical specialty societies, and advocacy groups.19 These quality measures are then incorporated by CMS into payment programs, in an effort to tie reimbursement to quality. Broadly speaking, quality measures are a series of benchmarks that CMS uses to incentivize quality by requiring individual physicians or physician groups to report their performance on the measures, then adjust reimbursement based on how well certain benchmarks are met. These benchmarks can also be compared among physicians and hospitals, allowing the public to ascertain the “quality” of care assigned by the benchmark. Metrics can vary in the characteristics they might be measuring, some related to the process of care and some to compliance with medical literature (examples in Table 10.1). Some have even proposed quality metrics related to chief complaints, a proposal that seeks to more accurately match quality measures with the nature of emergency department care, focused on effectively risk-stratifying patients based on their presenting symptoms.20

The passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) solidified the transition toward “value-based programs”.1,2,21 Presently, CMS uses these benchmarks in the Quality Payment Program, a program designed to reward facilities and organizations that perform better on the benchmarks with higher payments and penalize those that do not meet metrics.21

Most emergency physician groups participate in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Within MIPS, there are multiple “tracks” or “pathways,” customizable to the individual needs and capabilities of a practice.3 Current reimbursement models depend on a composite performance score from four separate categories:

- Quality

- Clinical Practice Improvement Activities

- Promoting Interoperability

- Cost

Participating physicians report on relevant data in these categories to calculate a MIPS composite score. The composite score is compared to a pre-assigned threshold then CMS calculates final payment adjustments applied to Medicare Part B claims from that physician. The MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) are a newer subset of methods to participate in MIPS set to debut in 2023.

Current State of the Issue

Prior to the passage of MACRA in 2015,22 CMS used three main pay-for-performance systems to encourage quality in patient care: Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Payment Modifier, and the Electronic Health Record incentive program. These programs were combined to create the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). The purpose of MIPS is to measure performance, with above average physicians receiving a bonus and below average physicians receiving a penalty. As mentioned previously, MIPS has four performance categories:4,8

- Quality

- Clinical Practice Improvement Activities

- Promoting Interoperability

- Cost

The scores in each category are added to determine payment adjustments.

Physicians can participate in MIPS through quality reporting registries. ACEP has developed the Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR).5 CEDR aims to measure outcomes and patterns in emergency medicine by taking input from emergency physicians and departments across the country. All information is collected from an ED’s electronic medical record and used to both satisfy CMS quality measure reporting requirements and provide helpful feedback to physicians and groups on practice patterns. CMS has approved CEDR as a Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR) that satisfies MIPS reporting.6

CEDR QCDR has several measures that are approved for MIPS, including CT use for minor blunt head trauma, sepsis management, length of stay, avoidance of opiates for low back pain and migraines (ACEP CEDR measures). The goal is to use metrics that were developed within the specialty of emergency medicine and are therefore more applicable to our practice. CEDR also provides feedback to physicians on their performance compared to their peers nationally. This registry allows for individual quality improvement and also national data that can be used to guide policymakers.

CMS uses several criteria when examining new quality measures: importance, feasibility, scientific acceptability, usability and use, and comparison to related or competing measures. Input from a multitude of stakeholders is reviewed as each measure is considered. This can include expert panels, public comments, health care professionals, family members, advocacy groups, health care organizations, other government agencies, and academic researchers. CMS also offers an annual call for submissions where clinicians and organizations representing clinicians can submit new measures.23

As MIPS metrics are tied to clinician compensation, there is a concern that they can detract from patient care by focusing physicians on metrics instead of patients. Another issue is whether certain metrics should be used at all. In the ED, patient length of stay increases whenever a hospital is at capacity and patients are boarding. Both of these factors are far outside the control of the individual emergency physician but nevertheless may affect compensation if the “length of stay” quality measure is used.

Moving Forward

The goal of the emergency physician is to provide the best possible patient care. Quality metrics tied to provider compensation should emphasize specialty-driven and evidence-based quality metrics. Emergency physicians can offer insight into metrics that are important to our practice and advocate against metrics that impair, impose unintended consequences, or do not otherwise reflect the standard of care. Quality measures for emergency care should also consider the inherent risk that comes with treating patients for acute, unscheduled care in an environment flush with distractions, impediments, and barriers to the optimal practice of emergency medicine.

TAKEAWAYS

- Quality measures are now an integral part of reimbursement for emergency care

- Emergency physicians must be involved in determining quality measures that are evidence based, and appropriately risk adjusted for our care setting.

- MIPS measures performance, with above average physicians receiving a bonus and below average physicians receiving a penalty.

- ACEP’s Clinical Emergency Data Registry uses metrics developed within the specialty of emergency medicine, and are therefore more applicable to our practice.

- Quality measures impact physician reimbursement, and often have the underlying goal of saving money for payors and increasing risk for the institutions and professionals providing health care.

References

- Value-Based Programs. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed on May 28th, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs

- Roadmap for Implementing Value Driven Healthcare in the Traditional Medicare Fee-for-Service Program. PDF available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/downloads/vbproadmap_oea_1-16_508.pdf.

- Quality Payment Program Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed on May 28th, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/about/qpp-overview

- Reporting Options Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed on May 28th, 2022. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/reporting-options-overview

- American College of Emergency Physicians- Clinical Emergency Data Registry. Qualified Clinical Data Registry. Accessed June 6, 2022 Clinical Emergency Data Registry (CEDR) // QCDRS (acep.org)

- Services CfMaM. Quality Payment Program: Merit Based Incentive Program (MIPS) Scoring 101 Guide for Year 2 (2018)

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2022, November). Understanding Quality Measurement (US Department of Health and Human Services) Retrieved November 11, 2022, from: Understanding Quality Measurement | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ahrq.gov)

- Griffey RT, Pines JM, Farley HL, et al. Chief complaint-based performance measures: a new focus for acute care quality measurement. Ann Emerg Med. 2015; 65: 387-95.

- Kamphuis CB, Turrell G, Giskes K, Mackenbach JP and van Lenthe FJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular mortality and the role of childhood socioeconomic conditions and adulthood risk factors: a prospective cohort study with 17-years of follow up. BMC public health. 2012; 12: 1045.

- Kauhanen L, Lakka HM, Lynch JW and Kauhanen J. Social disadvantages in childhood and risk of all-cause death and cardiovascular disease in later life: a comparison of historical and retrospective childhood information. International journal of epidemiology. 2006; 35: 962-8.

- Nordahl H. Social inequality in chronic disease outcomes. Danish medical journal. 2014; 61: B4943.

- Ullits LR, Ejlskov L, Mortensen RN, et al. Socioeconomic inequality and mortality--a regional Danish cohort study. BMC public health. 2015; 15: 490.

- Examination and treatment for emergency medical conditions and women in labor, 42 U.S.C 1395dd

- Houck PM, Bratzler DW, Nsa W, et al. Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for Medicare patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 637-644.

- Meehan TP, Fine MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Quality of care, process and outcomes in elderly patients with pneumonia. JAMA. 1997;278:2080-2084.

- Maniago EM, Nguyen M, Roccanova A, et al.419: JCAHO-CMS PN-5b: Does Compliance With the 4-Hour Antibiotic Rule Affect Outcomes in Pneumonia Patients? Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007: 50(3), S131–S132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.468

- Fee C & Weber E. Identification of 90% of Patients Ultimately Diagnosed With Community-Acquired Pneumonia Within Four Hours of Emergency Department Arrival May Not Be Feasible. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007: 49(5), 553–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.008

- Pines J, Hollander J, Lee H, et al. Emergency Department Operational Changes in Response to Pay-for-performance and Antibiotic Timing in Pneumonia. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007: 14(6), 545–548. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2007.01.022

- Wennberg JE, Brownlee, S., Fisher, E.S., Skinner, J.S., Weinstein, J. N.,. An Agenda for Change Improving Quality and Curbing Health Care Spending: Opportunities for the Congress and the Obama Administration. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice. 2008: 17.

- National Quality Forum Measure Applications Partnership. Accessed June 6, 2022. NQF: Measure Applications Partnership (qualityforum.org)

- Griffey RT, Pines JM, Farley HL, et al. Chief complaint-based performance measures: a new focus for acute care quality measurement. Ann Emerg Med. 2015; 65: 387-95

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed on May 28th, 2022.https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs

- Measures Management System. CMS. https://mmshub.cms.gov/ Accessed November 11, 2022.