Ch. 4. Health Beyond Health Care: Social Determinants of Health

Sriram Venkatesan, FAWM; Mackensie A. Yore, MD, MS; Valerie A. Pierre, MD, FAAEM

Chapter 4. Health Beyond Health Care: Social Determinants

Recorded by Sriram Venkatesan, MD, FAWM | Sri Ramachandra University

Social circumstances play a consequential role in the health of patients with complex needs (lack of housing, substance use disorders, mental health disorders, etc.). As part of the frontline medical team, emergency physicians are obligated to stand up and advocate on behalf of their patients to provide optimal patient-centered care.

Systems of emergency care are evolving to respond more holistically to patient needs and to raise awareness of the role of social and structural factors on both individual and public health.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

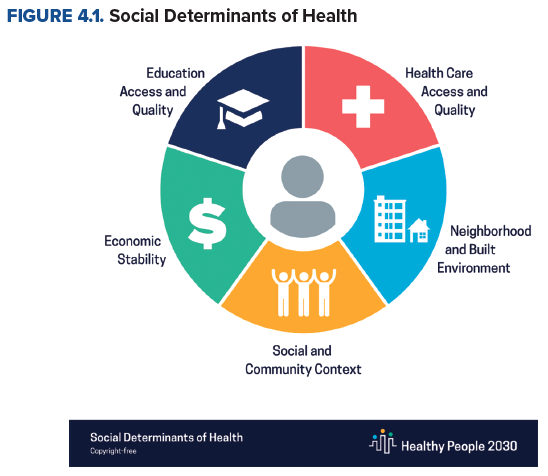

The ED is the gateway to the health care system, accessible at all times to our country’s most vulnerable patients, regardless of their socioeconomic background. Millions of Americans, impacted by social needs, rely on the ED for routine and urgent medical care. For this reason, it is often referred to as a “window into the community,” through which emergency medicine providers regularly witness and care for people affected by disparities associated with adverse social determinants of health (SDoH).1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines SDoH as “conditions in the places where people live, learn, work, and play, that affect a wide range of health and quality-of-life-risks and outcomes.”2 According to data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, the high reliance on ED services was largely due to non-health care factors, including education, employment, and poverty concentration that had nearly as strong a relationship with ED utilization as health status.3 Given the complex needs of many ED patients, physicians should strive to address the medical and social needs of each patient we encounter, to give equitable care across the board.

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, emergency medicine played an integral role in meeting the challenges of this crisis. As one of the few specialties with direct patient contact at the time, emergency physicians were uniquely positioned to correct public misconceptions and promote more appropriate social distancing, mask wearing, and other health and hygiene practices. The shift in public perceptions based on current communications in the United States presented EM with a rare outlet to spearhead patient education efforts about the virus.4 While their normal scope of duties is typically limited to engaging with patients to coordinate their immediate care, the COVID-19 pandemic provided the opportunity to have more broad-ranging conversation with the public about a multitude of health topics. The COVID-19 response also led to emergency physician leadership in various levels of government and the private sector, providing an opportunity to advocate for the broad determinants of health impacting our patient population. Since then, there has been greater demand for emergency physicians to take up larger roles in various areas of government and public health spheres, to draft and lead future emergency response plans and guidelines.5

How We Got to This Point

One of the first notable discussions addressing SDoH can be traced all the way back to the early 18th century as a response to the Industrial Revolution. Rudolf Virchow, a German physician and statesman known for his work in pathology and forensics, famously wrote, "If medicine is to fulfill her great task, then she must enter the political and social life. Do we not always find the diseases of the populace traceable to defects in society?" in response to the typhoid epidemic in the 1840s.6

The concept of SDoH, however, was not introduced to U.S. policy until much later, when President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a war on poverty in his State of the Union address on Jan. 8, 1964. He subsequently signed the Economic Opportunity Act, which led to the eventual rise of several federal programs including Medicare, Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Job Corps, and Head Start.7 Social issues that predominantly affect impoverished communities, such as crime, hunger, housing, and transportation were recognized by most of the country; however, they were not adequately addressed until almost 20 years later, when hospitals began hiring social workers to connect patients with community support services. In 2010, the U.S. Congress passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, colloquially known as Obamacare. The law aimed to promote overall public health, recognizing the association between poverty, lack of health insurance, and health care disparities. Through Obamacare, a $10 billion fund to expand national investments in prevention and public health was established.7

Since then, the health care community in the U.S. has steadily tried to incorporate SDoH-centered care into practice. Political disagreements over the future of publicly funded health care, however, kept health policy innovation mostly stagnant until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The sharp increase in health care utilization combined with the universal lockdown and social distancing created a “perfect storm” of challenges that rocked much of health care to its core. A study by the CDC that surveyed more than 16,000 families during the peak of the pandemic in 2020 highlighted this compounding effect that COVID-19 had on households, across the spectrum of social needs. The study revealed that 76.3% reported concerns about financial stability, 42.5% about employment, 69.4% about food availability, 31.0% about housing stability, and 35.9% about health care access.8 Another study conducted by Feeding America, a U.S.-based nonprofit with a nationwide network of more than 200 food banks, showed that 45 million adults (1 in 7) and 15 million children (1 in 5) experienced food insecurity in 2020.9 SDoH was suddenly forced back into the limelight and became such a focus that CMS created a "roadmap" to help states address the root causes in order to "improve outcomes, lower costs, and support state value-based care strategies." Then-CMS administrator Seema Verma said, "The evidence is clear: social determinants of health, such as access to stable housing or gainful employment, may not be strictly medical, but they nevertheless have a profound impact on people's wellbeing."10

Today, SDoH remains a major focus in health equity conversations across the country. As of June 2022, there are 114 bills before the U.S. Congress that mentions SDoH in some form, and public and private sector corporations are increasingly looking into new ways to set measurable, practical goals to play their part in guaranteeing equal access to resources for all.11

Current State of the Issue

Our field’s efforts to address social conditions that affect health have grown in recent years and taken many forms. These efforts have included raising awareness about the influence of social and structural factors on health, examining the role of bias and discrimination in medicine in contributing to health inequities, including social workers and case managers in the ED care team, implementing ED-based screening and intervention programs for social needs, and advocating for health, social, and economic policies.

The Emergency Medicine Model of Clinical Practice, developed by the leading accreditation, curricular, and professional organizations in emergency medicine lists the ability to "recognize age, gender, ethnicity, barriers to communication, socioeconomic status, underlying disease, and other factors that may affect patient management" as a core task for emergency physicians.12 In line with this objective, EM training and continuing education has begun to include a greater emphasis on the SDoH and building skills to ask patients about and consider their material needs when developing treatment and disposition plans. This has been done in a variety of ways, including development of EM-specific SDoH curriculum, SDoH-related journal clubs, and neighborhood walking tours to shelters, food banks, and other locations that provide social resources.13-15 Along with SDoH, there has been increasing awareness of the structural determinants of health, which are economic systems, institutions (eg, health care, education, carceral), and policies that underlie social conditions, affect individual agency, and place disproportionate burden on underprivileged groups.16 Many physicians still have little exposure to historical issues like redlining, that impact the health of the communities they serve. General competencies to understand and address the structural determinants of health as a clinician have also recently been translated for an EM audience.17 More resources to educate trainees and physicians on the history of discriminatory housing/lending policies, the stark health disparities rooted in gun violence, lead levels, access to primary care, and life expectancy have also proven to be effective.

The field of EM has also started to acknowledge the ways in which it, and the institution of medicine more broadly, has contributed to health inequities. We now understand that there are racial and other demographic differences in the care delivered in the ED. For example, recent research has shown that Black, Latino, and Native American patients receive lower acuity triage scores than white patients for similar clinical conditions and that Black and Latino men on involuntary psychiatric holds are more likely than other patients on psychiatric holds to be placed in physical restraints.18,19 There has been a call to action for doctors to do better, for example, by participating in anti-bias training, supporting underrepresented minorities in medicine to enter and remain in the field, learning about the history of race and racism and America and how racism affects health, and reporting excessive force by police manifesting in injuries treated in the ED.20

EM has been increasingly recognized as an interdisciplinary and collaborative field that needs the expertise of social workers and case managers as much as it does physicians and nurses to deliver high-quality care. Social workers and case managers now routinely help with follow-up care, discharge planning, and additional resources for intimate partner violence and substance use disorders. While a recent study in New England showed that 93% of EDs now have access to a social worker at certain times, only 27% have access 24/7, which in many places severely limits the capacity of social workers to go a step further and address other types of medically-relevant social needs such as housing, lack of transportation, and food insecurity.21 To fill this gap, some EDs have experimented with or implemented comprehensive social needs screening and navigation programs in which non-clinical staff or volunteers administer social need screening questionnaires to patients and families and facilitate connections to resources these families may be interested in to fulfill their needs.22,23

EDs have begun adding other new programs to address specific social needs and access to care issues. For example, some centers have started COVID-19 vaccination programs, for which ACEP offers a toolkit and other resources on their website, expanding access to vaccines for patients who may not have a primary care physician or another way to discuss vaccine-related questions.24 Emergency physicians across the country have also brought the Vot-ER program to their EDs, helping to integrate voter registration into health care delivery.25

In some cases, new state-wide policies have introduced mandates that EDs offer certain social resources. For instance, in 2019, California passed Senate Bill (SB) 1152, requiring that homeless patients be offered a bundle of resources at discharge from the hospital or ED to ensure their safety. While the passage of the bill has motivated more robust ED screening for homelessness and, in many places, a good-faith effort to offer additional resources to homeless patients, the shortcomings of the bill, namely the lack of funding to support housing navigators to continue to work with patients on finding housing after discharge and additional funding for the shelter system, have also been widely recognized and hampered its impact.26 If future iterations of SB 1152 include additional support, such as a funding mechanism for housing navigation, this legislation could be a model for other states wanting to better support persons experiencing homelessness.

In summary, emergency physicians are becoming increasingly attuned to the social and structural determinants of health and health inequities and their impact on patients in the ED. While the ability to comprehensively address SDoH in the ED is hampered by funding, many EDs now offer at least some social resources to patients even on a constrained budget.

Moving Forward

The EMRA Policy Compendium includes a variety of position statements regarding SDoH. EMRA explicitly mentions advocacy priorities that include women’s and reproductive health, reforms of the criminal justice system and equitable care for incarcerated patients, firearm safety and injury prevention legislation, health disparities research, increased coverage for mental health disorders, classification of substance use disorder as a chronic and progressive medical condition, and opposition of family separation for undocumented immigrants at national borders.27 The Policy Compendium also mentions specific EMRA goals for the specialty, including (but not limited to) developing and implementing more curriculum and training on the role of EM in public health, preventive medicine, and social medicine, and creating additional research support for studies on the relationship between SDoH and health outcomes.

The specialty of EM has made great progress in recent years increasing awareness of the role of social and structural factors on health, and yet, additional steps need to be taken for EM to completely fulfill its social mission. Advocates of social emergency medicine and a more holistic approach to care can help by asking for and supporting additional funding for social work and case management support in the ED, helping their EDs strengthen relationships with community agencies offering social resources, researching evidence-based strategies for screening for and addressing SDoH, and continuing to work toward equity in health outcomes for all patients.

TAKEAWAYS

- Systems of emergency care are evolving to respond more holistically to patient needs, attending to both the immediate medical concern and working in multi-disciplinary teams that include social workers, case managers, other nonclinical staff to identify social determinants of health and facilitate connection with social resources.

- The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated and laid bare many adverse social determinants of health that will continue to be important issues for advocacy in the future.

- The EMRA Policy Compendium includes a variety of position statements regarding SDoH, which emergency physicians and trainees in EM can refer to for talking points and ideas when discussing potential policies with local, state, and federal legislators.

References

- Walter LA, Schoenfeld EM, Smith CH, et al. Emergency department–based interventions affecting social determinants of health in the United States: A scoping review. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(6):666-674.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm. Published September 30, 2021.

- Murad Y. In the Emergency Room, Patients’ Unmet Social Needs and Health Needs Converge. Morning Consult. Published May 8, 2020.

- Gaeta C, Brennessel R. COVID-19: Emergency Medicine Physician Empowered to Shape Perspectives on This Public Health Crisis. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7504.

- Pikul C. Megan Ranney elected to the National Academy of Medicine. Brown University. Published October 17, 2022.

- Klag MJ. Politics May Be a Dirty Word But It's Also an Essential Means for Improving Health. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Published November 13, 2014.

- Johnson SR. In Depth: Hospitals tackling social determinants are setting the course for the industry. Modern Healthcare. Published February 15, 2019.

- Sharma SV, Chuang R, Rushing M, et al. Social Determinants of Health–Related Needs During COVID-19 Among Low-Income Households With Children. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published October 1, 2020.

- Feeding America. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Local Food Insecurity. 2020. Accessed at https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Brief_Local%20Impact_5.19.2020.pdf.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Issues New Roadmap for States to Address the Social Determinants of Health to Improve Outcomes, Lower Costs, Support State Value-Based Care Strategies. Published January 7, 2021.

- Library of Congress. Legislative Search results: Social Determinants. https://www.congress.gov/search?q=%7B%22source%22%3A%22legislation%22%2C%22search%22%3A%22social+determinants%22%2C%22congress%22%3A117%7D. Accessed June 11, 2022.

- Counselman FL, Babu K, Edens MA, et al. The 2016 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(6):846-849.

- Smith KJ, Harris EM, Albazzaz S, Carter MA. Development of a health equity journal club to address health care disparities and improve cultural competence among emergency medicine practitioners. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(Suppl 1):S57-S64.

- Cross JJ, Arora A, Howell B, et al. Neighbourhood walking tours for physicians-in-training. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1156):79-85.

- Moffett SE, Shahidi H, Sule H, Lamba S. Social Determinants of Health Curriculum Integrated Into a Core Emergency Medicine Clerkship. MedEdPORTAL J Teach Learn Resour. 2019;15:10789.

- Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126-133.

- Salhi BA, Tsai JW, Druck J, Ward-Gaines J, White MH, Lopez BL. Toward Structural Competency in Emergency Medical Education. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(Suppl 1):S88-S97.

- Zook HG, Kharbanda AB, Flood A, Harmon B, Puumala SE, Payne NR. Racial Differences in Pediatric Emergency Department Triage Scores. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(5):720-727.

- Carreras Tartak JA, Brisbon N, Wilkie S, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department restraint use: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(9):957-965.

- Brown C, Brown K, Brown I, Daniel R. Dear White People in Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(5):587-592.

- Samuels-Kalow ME, Boggs KM, Cash RE, et al. Screening for Health-Related Social Needs of Emergency Department Patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(1):62-68.

- Wallace AS, Luther B, Guo JW, Wang CY, Sisler S, Wong B. Implementing a Social Determinants Screening and Referral Infrastructure During Routine Emergency Department Visits, Utah, 2017–2018. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:190339.

- Losonczy LI, Hsieh D, Wang M, et al. The Highland Health Advocates: a preliminary evaluation of a novel programme addressing the social needs of emergency department patients. Emerg Med J. 2017;34(9):599-605.

- Setting Up Vaccination Programs in the ED. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.acep.org/corona/COVID-19-alert/covid-19-articles/vaccination-programs-in-the-ed/.

- Vot-ER. Published May 25, 2020. Accessed June 16, 2022. https://vot-er.org/aboutus/.

- Taira BR, Kim H, Prodigue KT, et al. A Mixed Methods Evaluation of Interventions to Meet the Requirements of California Senate Bill 1152 in the Emergency Departments of a Public Hospital System. Milbank Q. 2022;100(2):464-491.

- Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association. EMRA Policy Compendium. Published November 2021.

- Tracking the COVID-19 economy's effects on food, housing, and employment hardships. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and.