Ch. 21. The Fourth Branch of Government: Regulatory Issues

Melanie Yates, MD; Rebecca Leff, MD; Chadd K. Kraus, DO, DrPH, CPE, FACEP

Chapter 21. The Fourth Branch of Government: Regulatory Issues

Recorded by Ellen Shank, MD | UC-Davis

Physician advocacy is often focused on elected officials. However, emergency physicians can engage in effective advocacy targeting the regulatory process, including federal regulatory agencies, the so-called “Fourth Branch of Government.”

Regulatory agencies are the governmental entities that administer the laws passed by the legislature. These bureaucracies clarify, interpret, and enforce how legislative mandates will be implemented in practice.

After a bill becomes law, a regulatory agency first interprets the law itself, and then sets up rules for how it will enforce its interpretation of the law.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

Policies impacting the practice of emergency medicine are determined at both the legislative and regulatory level, making regulatory advocacy an important tool to impact change. Regulatory agencies administer the laws passed by the legislature, including agencies you may be familiar with such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When Congress enacts legislation directing an agency to perform a task, the agency may then issue regulations that further interpret the language used in the original legislative text. In other words, regulations are laws “in action,” issued to practically carry out the intent of enacted legislation in everyday life. The regulatory rules, process, and details often far exceed the volume and detail of the underlying enabling legislation.

Consider, for example, that laws applying to emergency departments rely on how regulatory agencies define the term “emergency department.” After EMTALA was passed, the Department of Health and Human Services defined an “emergency department” to include hospital-affiliated EDs, but not independent, freestanding EDs. This means that EMTALA regulations do not apply to many independent freestanding EDs, as they do not qualify as emergency departments under the regulatory agency’s definition of the term.

The implications of this definition mean that EM physicians bill for emergency care only at hospital-affiliated EDs, while at independent freestanding EDs, care can only be billed to Medicare as a general office visit. The EMTALA legislation further dictates that EMTALA obligations are triggered when a person “comes to” an emergency department. But it is the role of the regulatory agency to define if this term applies to the moment a person walks through the door, reaches the sidewalk in front of the ED, enters a hospital-owned ambulance, or parks their car in a hospital parking lot. In fact, federal regulations clarify that a person is considered to have “come to” the ED just by standing on a hospital’s parking lot or adjacent sidewalk even if they have not physically entered an ED.

Given the significance of the regulatory process, regulatory agencies such as CMS are not conventionally staffed by actively practicing health care providers. Thus, regulators may define terms or address issues in a manner that is inappropriate or adverse to the practice of emergency medicine. They may use language that is inaccurate, problematic, or not commonly accepted by emergency medicine clinicians.

Agencies generally can issue, modify, or amend regulations without seeking additional approval from Congress. One example of this was a June 2013 memorandum from CMS that clarified the regulations for physician coverage requirements. Under the Conditions of Participation for critical access hospitals and EMTALA, this availability coverage could be fulfilled when non-physician providers at critical access hospital EDs are equipped with ED-based telemedicine. This is different from the previously accepted understanding, which required a physician to be onsite to respond in person to emergencies, even in such cases where an ED is staffed by a qualified NPP. In practice, this means that substantial alterations can be made between the time a bill is signed into law and the time that rules for implementation are written and enforced at agency discretion.

Therefore, the changes that take place as part of the regulatory process can reverse significant legislative achievements by clinicians if agencies put into practice an adverse interpretation or administration of a new or existing law. Alternatively, working with these same agencies can sometimes palliate a legislative loss. Regulatory advocacy can be as important, or even more important, than the initial legislative advocacy to get a proper resolution.

How We Got to This Point

From a historical standpoint, the first nationally recognized law that allowed for regulations was enacted in 1887, known as the Interstate Commerce Act.1 This allowed for the first regulatory commission to limit railroad rates. Throughout the 20th century, there were further expansions of regulatory bodies by Congress and the executive branch. In 1946, the Administrative Procedure Act was passed, which was likely the first regulatory reform bill and governed the way by which federal agencies develop and issue regulations.2,3 This has led to the formation of departments and agencies that are in charge of creating and implementing regulations based on instituted laws, such as the Department of Health and Human Services, which houses the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevent (CDC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This process is similar at the state level, but it may vary based on each state’s constitution and administrative procedures.

After a bill becomes law, a regulatory agency first interprets the law itself, and then sets up rules for how it will enforce its interpretation of the law. During this pre-rule period an agency may gather more information before issuing a mandatory notice of proposed rulemaking. From there, these preliminary rules must be made available to the public via the Federal Register for comment. This comment and question period, which is 30 days on the federal level and may vary by state, is a key window during which citizens, physicians, and organizations can advocate for specific changes to the rules prior to full implementation. Public hearings may also be conducted at this time and serve as an additional opportunity for advocates to articulate their position on an issue. The Final Rule published must recognize all substantive comments received during the comment period, as well as explain how the agency addressed them. The Final Rule is promulgated in the Federal Register and includes an effective date, which is generally no sooner than 30 days after rule publication. Once a final rule is issued, the comment period for that rule has ended, and advocates will need to consider other strategies to address any concerns with a given rule.

For an example of this process in action at the federal level, the “No Surprises Act’’ was signed into law on Dec. 27, 2020. Initial regulations were drafted by multiple regulatory bodies, including the Personal Management Office, IRS, Employee Benefits Security Administration, and the HHS Department. These initial regulations were then made available for public comments, and an interim rule was issued to restrict surprise billing for patients seeking emergency and non-emergency care from out-of-network providers at in-network facilities on July 1, 2021. There are currently two rules still available for public comment, the second interim final rule for establishing the dispute process for payments, and the third interim final rule for the submission of information on prescription drug prices and health care spending. While the law was passed at the end of 2020, the actual implementation of the “No Surprises Act” is still being determined at the regulatory level.4

Health services research can be a key factor in the influence of rules and regulatory changes. Research into legislation and then the following implementation of the law may be able to identify possible harms and benefits of policy and its rules, estimate costs for private and government sectors, and better define the problem that a rule can help fix.5 This type of research has assisted in forming legislation and regulations that improve the process for addressing medical errors, implementation of value-based care into the Affordable Care Act, and mental health parity.5 Active health services research is constantly needed and sought after to help advocate for evidence-based regulations and rules from multiple state and federal organizations like ACEP or from government agencies, such as the HHS, CMS, or CDC.

Current State of the Issue

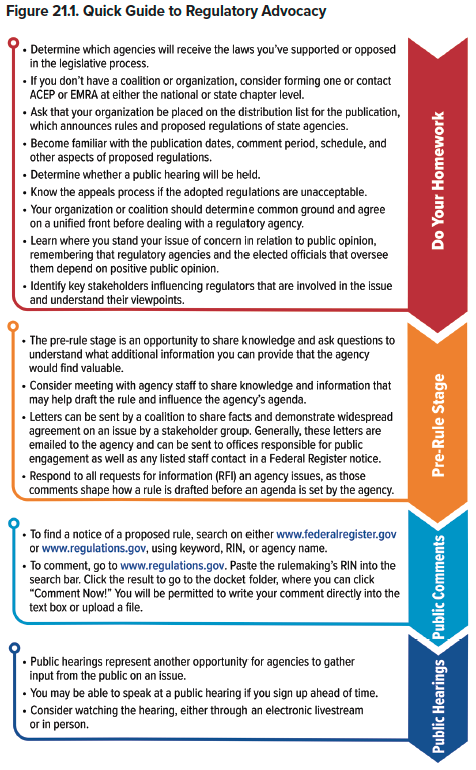

There are two important opportunities for advocacy to influence proposed regulations: the pre-rule stage and public commentary stage, including public hearings. During the pre-rule stage, agencies formulate a draft rule based on the administrative agenda and wording of legislation. This means any pre-rule comments and questions from organizations and individuals will be extremely beneficial in creating the regulation. During the public comment period, organizations and private citizens can advocate via public hearings and online comment forums to influence the wording of the final rule.

ACEP and EMRA, along with many other health care organizations, keep track of multiple rules that have the power to affect health care providers and patients. From here, these organizations will reach out to their members to ascertain a consensus on the rules being proposed, and what changes members might like to see. The organizations will then submit informed member and stakeholder feedback. In addition, individuals can submit informed comments about specific rule proposals via www.regulations.gov.

Moving Forward

There are multiple important current issues to keep an eye on over the next year, including COVID-19 regulations, the No Surprise Act and its regulations, Medicare payments and policies such as telehealth, violence in the ED, and medical management of opioid use disorder. ACEP monitors and reports on federal regulatory issues that will affect the specialty, through its Regs & Eggs newsletter for members.6

As private citizens, we have the ability to comment on proposed regulations. As emergency physicians, we have a unique perspective on how suggested regulations can affect our patients, our practice, and our future as a specialty.

Every citizen has easy access to comment on these possible rules. In addition, ACEP and EMRA will often elicit feedback from members for thoughts on specific regulations to form a consensus opinion that will be used to propose changes to the preliminary rules presented by the regulatory agencies. There will always be new laws and rules that will require our advocacy in order to protect our patients and practice.

TAKEAWAYS

- For federal and state laws to be implemented, rules must be created, reviewed and revised, and then finalized by regulatory agencies.

- Regulatory advocacy can be as important as your original legislative advocacy to make effective change.

- There is a public comment period for all rules, and it’s important for physicians and organizations to weigh in.

- Keep up to date on when to advocate for regulatory changes during the allotted commentary time frame.

- Get involved with health services research. It helps organizations and agencies advocate for better-informed policies and regulations.

References

- The Interstate Commerce Act is passed. United States Senate; Feb. 4, 1887. Accessed at https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Interstate_Commerce_Act_Is_Passed.htm.

- Dudley SE. A brief history of regulation and deregulation. The Regulatory Review. March 11, 2019. Accessed at https://www.theregreview.org/2019/03/11/dudley-brief-history-regulation-deregulation/.

- Administrative Procedure Act (5 USC Subchapter II). National Archives. Accessed at https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/laws/administrative-procedure.

- Implementation of the No Surprise Act. American Medical Association. Accessed at: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/patient-support-advocacy/implementation-no-surprises-act.

- Clancy CM, Gilded SA, Lurie N. From Research to Health Policy Impact. Health Serv Res. 2012 Feb; 47(1 pt 2): 337-343.

- Regs and Eggs. ACEP. Accessed at https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/federal-advocacy-overview/regs--eggs/.