Ch. 3. The Plumbing Is Broken: Hospital-Based Congestion

Nathaniel Schlicher, MD, JD, MBA, FACEP

Chapter 3. The Plumbing Is Broken: Hospital-Based Congestion

Recorded by Maria Jones, DO | Christiana Care Health System

The challenges of flow through and out of emergency departments have long been present, but the post-pandemic surge in volume, coinciding with a health care staffing crisis, pushed the situation to unprecedented and unsustainable levels.1-3 The now all-too-familiar practice of boarding inpatients in EDs, resulting in overcrowding for those seeking emergency care, has increasingly negative effects on the care to those most in need.

By targeting the problem of boarding and crowding, the solutions that allow each facility to address their unique, specific causes can be the focus of future policy, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Why It Matters to EM and ME

Crowding is defined by a 2014 Congressional Research Service report as “a situation in which the need for services exceeds an ED's capacity to provide these services.” Boarding, meanwhile, is defined by ACEP as “the practice of holding patients in the ED after they have been admitted to the hospital because no inpatient beds are available.”4 Both crowding and boarding negatively impact patient care – and that, in turn, compounds the stress experienced by the entire care team. A stark example can be found in the 2021 case of Ray DeMonia, who sought help for a cardiac emergency. His overwhelmed local hospital contacted 43 surrounding facilities asking for an ICU bed – to no avail. He was eventually accepted by a hospital more than 200 miles away, but it was too late and DeMonia died.5 While a boarding-related death due to inpatient capacity is dramatic, all patients are negatively affected by inpatient boarding in the ED. Multiple studies documenting negative impacts on mortality, bouncebacks, length of stay, and patient satisfaction have resulted in increased calls for health science research on the true impact of this crisis.6

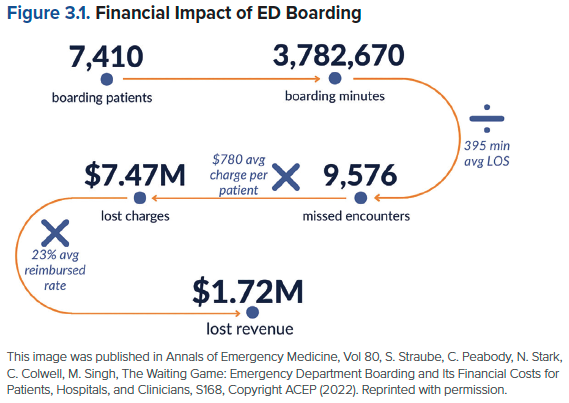

The impact of boarding is also profound on the care team. With increased delays, the stress in emergency departments continues to climb. Burnout among emergency medicine physicians remains high, with more than 60% of physicians suffering from burnout in multiple studies.7 Additionally, there has been a real financial cost to those that chose to deliver the care in multiple studies. One study reviewed a hospital's boarding problem and identified that it cost a single department nearly $2 million in lost revenue per year.8 That number skyrockets when the full impact of those lost visits, presumably a portion of which would have been admissions and high-revenue procedures, is taken into account. This reduced revenue then reduces the ability to provide staffing of the entire care team, resulting in further delays and a downward spiral of increasing delays, worsened outcomes, and more pressure on the care team.

How We Got to This Point

In the current health care system, emergency departments are responsible for more than just emergency care. Along with the original purpose of stabilizing seriously ill or injured patients, EDs fill the gaps in the overall health care system and often more broadly in the social services. EDs offer safety net care (for underserved populations), after-hours care, and management of acute exacerbation of chronic health issues. Addressing the social determinants of health has also become an increasing part of emergency care including housing and food resources. A significant gap in the supply and demand of primary and behavioral health care providers has added to the workload of emergency departments around the country as patients resort to an emergency visit when they can’t get appointments for routine care.

Despite speculations that implementation of the Affordable Care Act would decrease ED visits, ED utilization instead trended upward over time. Since the ACA's enactment, the type of payer visiting the ED initially changed, but the number of visits continued to rise in both Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states.9 That trend was jarringly disrupted in 2020, as COVID-19 emerged, and the world locked down. ED visits dropped from 143.4 million in 2019 to 123.3 million in 2020.10 Volume continued to drop in early 2021,11 and a subsequent staffing crisis – driven by financially motivated layoffs and burnout-fueled attrition – began to gather steam, with the worst shortages felt among the nursing staff. By March 2022, the American Hospital Association approached Congress with concerns of collusion and anticompetitive behavior by staffing companies, which it said was one of the factors driving crisis-level shortages of health care workers.12 In the end, there was a perfect storm of lower staffing and return of higher volumes that put the pressure on the staff providing care.

While there are multiple factors that have driven the challenges of inpatient boarding, the universal challenge has been that the EDs are the safety valve for the entire hospital. When inpatient beds are overfilled, the ED holds the patients through the practice of boarding. Profitable surgeries are not stopped to slow the influx of elective patient procedures. In contrast, the ED is always open, and the volumes on average are consistent and the admission rate a relatively predictable rate.13

With governmental entities at the regional and state level going to no-divert policies for EMS,14 the ability to turn off the inflow to the ED is eliminated. The addition of nurse staffing ratios in states like California can result in closed beds upstairs with patients boarding in the emergency department. Add to that shortages of mental health resources15 and outpatient care facilities, and the burden can become overwhelming on the one department that cannot say no. All roads lead to the ED care for inpatients and those struggling to access outpatient resources, thus diverting care and resources away from the new undifferentiated emergency patient in need of timely care that they increasingly cannot receive.

Current State of the Issue

Boarding has become so pervasive that emergency medicine conferences routinely host educational sessions on how to successfully conduct hallway medicine. Yet in 2021, CMS abandoned a quality measure tracking patients’ stay in the ED.16 Currently there is no financial incentive or quality metric that forces hospitals and health systems to address the inpatient boarding and overcrowding crisis. Without appropriate incentives, there is little impetus to drive change and investment in emergency department care that many health system executives see as costly and lower revenue-generating than elective surgical care.

As a result of this lack of current incentive to address this ever-increasing crisis, ACEP, joined by nearly 40 additional organizations from throughout the house of medicine, appealed to President Joe Biden in November 2022, asking the administration to recognize boarding as a major threat to public health and to prioritize solutions.17 More than 100 emergency physicians shared personal stories of the negative impact of boarding, reflecting profound moral injury and frustration over an inability to offer optimal care:18

"It's embarrassing to have such limited resources to offer patients who arrive in distress. I am aware of at least two cases where someone has died due to delays in being seen. Multiple providers have left our department due to the stress of an untenable work environment. We have been asked to do more with less to the point that it feels like we are expected to do everything with nothing."

As organized medicine seeks relief through policy measures, researchers are also calling on hospital system administrators to view the worsening crowding and boarding not as an ED efficiency problem, but as a hospital throughput issue.19,20 Unless efforts to address the problem are undertaken, there is little doubt that the crisis will continue to grow unabated.

Moving Forward

Solutions to the boarding and crowding issue can be grouped into two categories: internal and external to the emergency department. Much of the work in boarding and crowding to date have focused on the efforts to improve throughput in the emergency department through work on turnaround times, rapid triage and treatment, and alternative care locations. The pandemic and current staffing challenges have demonstrated in excruciating detail that the cause of boarding and crowding is mainly external to the department. While we can work to optimize care in the ED, any substantial improvement will come through addressing the external problems of surgical loading, inpatient bed management, long-stay patients, and other external drivers of overcrowding.

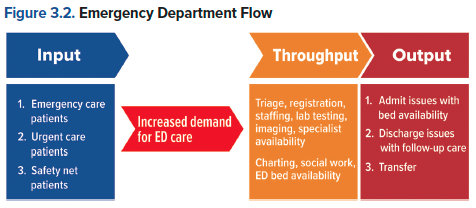

The ACEP Emergency Medicine Practice Committee’s guidelines focus on modifying input, throughput, and output of patients from the ED. This model can be useful in identifying factors that contribute to or relieve ED crowding (see figure).

While it’s important to know the pain points of crowding, the solution ultimately hinges on eliminating ED boarding – which requires systemic change. Teams are studying many potential ways to approach the issue:

- ED observation units:15 In a 2021 advisory, the Joint Commission recommended establishing observation units for psychiatric patients boarding in the ED, among other measures aimed at addressing mental health needs in a more timely manner.

- Multidisciplinary rounding:21 Studies have demonstrated reductions in length of stay on the inpatient medicine floor of a 30-bed regional transfer center after a multidisciplinary care team began daily rounds. These check-ins included focused discussion about expected discharge date, therapy and medication needs, discharge destination, and outpatient medical device requirements. "By implementing a daily MDR along with an improved understanding of how capacity and demand influence patient outcomes, reducing ED overcrowding and boarding became a mainstay for this project team."

- ED ICUs:22 Critically ill patients, by necessity, require the most resources – so boarding them in the ED is especially disruptive. An economic analysis showed that implementing an ED-based ICU improved quality without increasing cost.

- Hallway medicine:23 As subpar as it is, a simulation experiment showed boarding patients in hallways rather than in ED exam rooms could help improve throughput and overall hospital length of stay. Patients have also reported higher satisfaction with inpatient versus ED boarding. Regardless of the location, moving the patients out of the emergency department can increase flow and re-deploy ED staff to care for emergent patients.

- Patient flow teams and quality measures:24 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2018 released stepwise instructions to address crowding and boarding by improving patient flow. The report recommends assigning a team to implement and track quality measures, adjusting operations accordingly.

- Surgical level-loading:25 While ED admission volume is predictable and relatively steady, the surgical admission volume varies greatly over a week, concentrated towards the early weekdays resulting in peak boarding throughout the midweek. By smoothing surgical admission stays and leveling it over seven days of the week, excess hospital capacity can be utilized and the congestion in the ED reduced.

- Difficult to discharge patients: The challenge of an aging population with increasing chronic disabilities combined with behavioral health challenges can lead to prolonged stays in the inpatient hospitalization awaiting an accepting post-discharge facility.26 These patients are medically stable, but are unable to move out of the inpatient environment. This delay in discharge not only results in increased length of stay and overcrowding, but impacts hospital financial performance as no additional revenue is received, further increasing the potential for reduced staffing and resources. Addressing the barriers to discharge can help reduce overall congestion.

Each hospital and health system will have its own unique combination of causes of inpatient boarding that can include unbalanced schedules, difficult outflow, lack of staff, and inadequate physical plant space. Regardless of the cause, there are currently no financial or quality measures with significant pressure that can result in a systematic approach to addressing the problem. As such, arriving at a financial cost to continued poor care such as the work done with hospital readmissions or a quality incentive that could be attached to various standings like door-to-balloon time for heart center designation, will likely be required to make significant progress on the issue. To this end, ACEP created a task force on boarding and crowding in 2023 to begin to outline long-term systemic solutions to the problem that could be considered by the government and payers to help motivate the change we need to address the problem. By targeting the problem of boarding and crowding, the solutions that are unique to each facility to address their causes can be the focus rather than a one-size-fits-all approach to mandating solutions.

TAKEAWAYS

- Crowding is caused primarily by boarding and hospital inpatient bed availability, rather than low-acuity emergency visits.

- Boarding is a function of inefficient use of a fixed asset (hospital beds) to cap volumes. Maintaining high capacity helps a hospital’s bottom line, but allows little wiggle room for surges or pandemics.

- Lack of capacity in the system for mental health patients to get intensive outpatient or necessary inpatient care (especially special populations - children, pregnant patients, patients with medical comorbidities).

- Solutions to the problem must include appropriate financial and quality levers to motivate each organization to solve the unique causes of their lack of capacity.

References

- Janke AT, Melnick ER, Venkatesh AJ. Hospital occupancy and emergency department boarding during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233964.

- Janke AT, Melnick ER, Venkatesh AJ. Monthly rates of patients who left before accessing care in US emergency departments, 2017-2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233708.

- Johnson SR. Staff shortages choking US health care system. USNWR. July 28, 2022.

- ACEP Policy Statement: Definition of Boarded Patient. Accessed at https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/definition-of-boarded-patient.

- Bella T. Alabama man dies after being turned away from 43 hospitals as COVID packs ICUs, family says. The Washington Post. Sept. 12, 2021.

- Canellas MM, Kotkowski KA, Michael SS, Reznek MA. Financial implications of boarding: A call for research. West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(3):736-738.

- Straube S, Peabody C, Stark N, Colwell C, Singh M. 392 The Waiting Game: Emergency department boarding and its financial costs for patients, hospitals, and clinicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80(4):S168.

- Nikpay S, Freedman S, Levy H, Buchmueller T. Effect of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion on Emergency Department Visits: Evidence From State-Level Emergency Department Databases. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(2):215-225.

- Healthcare Cost & Utilization Project. Changes in Emergency Department Visits in the Initial Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic (April-December 2020), 29 States. Accessed at https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb298-COVID-19-ED-visits.jsp.

- CDC Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. Update: COVID-19 pandemic-associated changes in emergency department visits – United States, December 2020-January 2021. 2021;70(15):552-556.

- American Hospital Association. Letter Re: Challenges facing America’s health care workforce as the U.S. enters third year of COVID-19 pandemic. March 1, 2022.

- Weiner SG, Venkatesh AK. Despite CMS reporting policies, emergency department boarding is a big problem – the right quality measures can help fix it. Health Aff Forefront. March 29, 2022. Accessed at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220325.151088/.

- Letter to the President. Nov. 7, 2022.

- Emergency Department Boarding: A Nation in Crisis. Accessed at https://www.acep.org/administration/crowding--boarding/ed-boarding-stories/cover-page/.

- The Joint Commission. Quick Safety 19: ED boarding of psychiatric patients – a continuing problem. July 2021.

- Smalley CM, Simon EL, Meldon SW, et al. The impact of hospital boarding on emergency department waiting room. JACEP Open. 2020;1(5):1052-1059.

- Richards JR, Derlet RW. Emergency department hallway care from the millennium to the pandemic: A clear and present danger. J Emerg Med. 2022;63(4):565-568.

- Hammer C, DePrez B, White J, Lewis L, Straughen S. Enhancing hospital-wide patient flow to reduce emergency department crowding and boarding. J Emerg Nurs. 2022;48(5):603-609.

- Bassin BS, Haas NL, Sefa N, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an emergency department-based intensive care unit. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233649.

- Valipoor S, Hatami M, De Portu G, et al. Data-driven strategies to address crowding and boarding in an emergency department: a discrete-event simulation study. Health Environm Research Design J. 2021;14(2):161-177.

- McHugh M, Van Dyke K, McClelland M, Moss D. Improving patient flow and reducing emergency department crowding: a guide for hospitals. 2018. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/ptflow/index.html.