A 77-year-old man presented to the emergency department after being punched in the throat over a dispute involving a card game.

He reported immediate odynophagia, abnormal phonation, and small volume hemoptysis, but had no difficulty breathing.

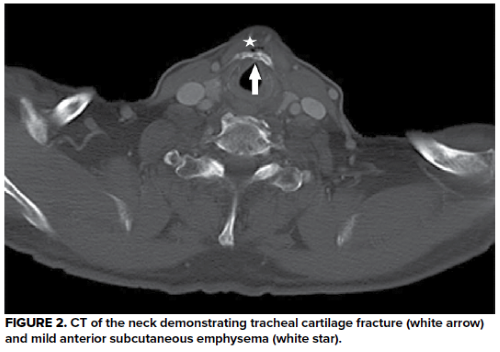

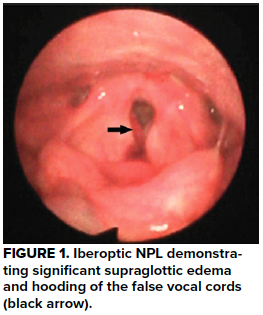

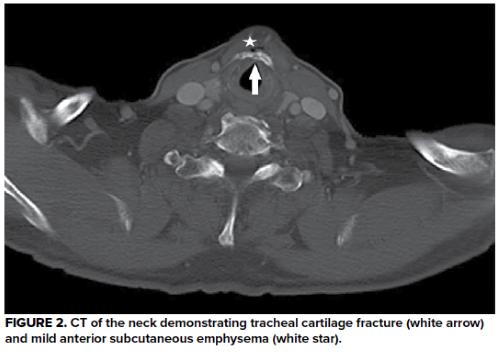

Physical exam was notable for anterior neck pain over the thyroid cartilage with palpable crepitus. Bedside nasopharyngolaryngoscopy (NPL) was performed (Figure 1), followed by a computed tomography (CT) of the neck with intravenous contrast (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Tracheal cartilage fracture with airway edema

Discussion

Tracheobronchial injury (TBI) is a rare, but potentially life-threatening, complication of neck trauma. It represents 1 in 30,000 ED visits per year. Fracture of the tracheal cartilage is most commonly the result of direct anterior blunt trauma, and can result in significant airway edema, tracheal laceration, hemoptysis, pneumothorax, and disruption of adjacent vascular structures. Cricoid cartilage fracture is associated with recurrent laryngeal nerve damage. NPL may demonstrate airway edema or bleeding. If the patient is stable, CT with contrast should be obtained to evaluate for significant tracheobronchial and vascular injuries in symptomatic patients following anterior neck trauma. Patients with tracheobronchial trauma have a high risk of other injury, especially with motor vehicle accidents, so imaging for C-spine injury and skull fractures should be obtained.

Early intubation with a fiberoptic scope, to ensure placement of the cuff distal to the site of injury, should be considered given the risk of progressive airway edema. An emergency cricothyroidotomy may also be necessary depending on the degree of trauma to the airway. Blind intubation should never be attempted due to the high risk of creating a false passage.

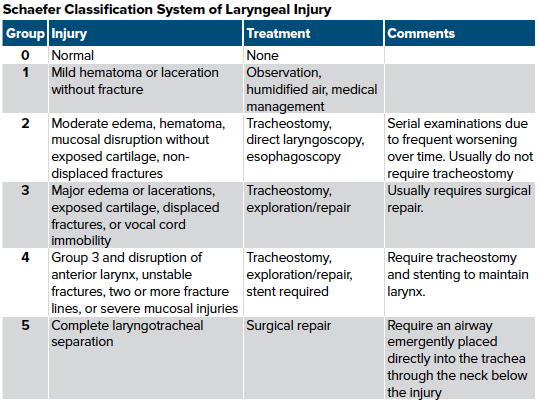

Surgical consultation should be obtained if the injury is severe enough to cause disruption of basic functions such as swallowing or phonation. Surgical options include observation, plating of fractures, or stenting of the airway. Displaced fractures will typically require open reduction in the operating room; 21% of patients who undergo surgical repair have phonation difficulties post-op.

Nonsurgical management options include elevation of the head of the bed to reduce edema and manage secretions, voice rest, cool humidified air to improve ciliary management of secretions, steroids for reduction of edema, and proton pump inhibitors to reduce laryngeal inflammation from acid reflux. Antibiotics may also be used as prophylaxis.

The most common cause of blunt neck trauma is motor vehicle accidents. Many of these accidents involve collision of the patient’s neck against the steering wheel or windshield. Other possibilities include sports accidents such as clothesline tackles. History and physical exam will typically reveal the symptoms seen in our patient, but can also involve respiratory distress, an expanding hematoma, edema, ecchymosis, or distorted anatomical landmarks. Adult thyroid and cricoid cartilages will typically fracture in multiple places due to ossification, whereas in children, they tend to fracture in one place. In children younger than age 3, the cricoid cartilage sits higher at C4, versus at C7 in most adults.

The neck is divided into 3 anatomic zones, with zone 1 being sternal notch to cricoid cartilage, zone 2 being cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible, and zone 3 being above the angle of the mandible. Hard signs of vascular injury, including expanding hematoma, bruit or thrill, or cerebral ischemia require immediate surgical consultation. In a stable patient such as ours with soft signs of injury (hemoptysis, dysphagia, dysphonia, subcutaneous air, and crepitus) a computed tomography angiogram is indicated.

Aerodigestive injuries can be very difficult to identify on initial presentation but should be pursued if clinically indicated (dysphagia, blood in gastric contents, or crepitus). These patients will typically require endoscopy or barium swallow to identify injuries. Antibiotics might also be indicated if suspected due to gastric contents.

Case Conclusion

In our patient, bedside NPL demonstrated significant supraglottic edema and hooding of the false vocal cords. CT confirmed tracheal cartilage fracture, with evidence of subcutaneous emphysema indicating an injury to the trachea. The patient was given dexamethasone and admitted to an ICU for airway monitoring and serial NPL examinations. His swelling improved after 2 days, and he was discharged with uneventful follow-up. He regained normal phonation and swallowing function several weeks after discharge. It is unclear if he ever played cards again with the same group that caused him to spend a night in the intensive care unit.

References

- Karmy-Jones R, Wood DE. Traumatic injury to the trachea and bronchus. Thorac Surg Clin. 2007 Feb;17(1):35-46.

- Huh J, Milliken JC, Chen JC. Management of tracheobronchial injuries following blunt and penetrating trauma. Am Surg. 1997 Oct;63(10):896-899.

- Shemmeri E, Vallières E. Blunt Tracheobronchial Trauma. Thorac Surg Clin. 2018;28(3):429.

- Johnson SB. Tracheobronchial injury. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;20(1):52-57.

- Lee WT, Eliashar R, Eliachar I, Acute external laryngotracheal trauma: Diagnosis and management. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85(3):179-184.

- Schaefer SD, Brown OE. Selective application of CT in the management of laryngeal trauma Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1473-1475.

- Moonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;7(2):210–216.