Airway management of expanding neck hematomas can challenge even the most expert of emergency clinicians. A myriad of decisions contributes to the complexity of these cases, such as timing of intervention, medications for induction, ancillary resources, equipment, and clinical picture.

Literature is robust in the discussion of expanding neck hematomas stemming from trauma or post-surgical complications. In this case, we highlight a unique presentation of a 67-year-old female presenting with a spontaneous thyroid hematoma originating from a thyroid nodule, and the distinctive challenges this presented that subsequently weighed heavily into management decisions. This case report highlights the importance of preparedness and management considerations in an atypical presentation of an expanding neck mass.

Introduction

The thyroid gland is a highly vascularized organ that encircles the anterior portion of the trachea, with the thyroid isthmus crossing just below the cricoid cartilage. Due to its location, acute expansion of a thyroid hematoma has the potential for airway compromise, and potentially fatal outcomes.

Previous literature points to factors such as anticoagulatio , intubation3, and trauma4,5 as risks of developing an acute thyroid hematoma. The goal of this case is to highlight a more unique presentation of spontaneous hemorrhage without clear risk factors. Additionally, we aim to discuss the management considerations of an expanding neck or thyroid hematoma, and specifically highlight the unique characteristics of this presentation that guided patient care.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old female with a past medical history of hypothyroidism initially presented to a small community emergency department with dysphagia and expanding pulsatile neck mass. The patient had awoken 30 minutes before arrival with marked swelling along the left anterior neck without any historical reports of trauma or recent surgery. Upon initial presentation to the outside hospital, the patient was noted to be without any evidence of respiratory distress, wheeze, stridor, or vocal changes. Examination of her neck revealed a firm pulsating mass (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expanding neck mass upon exam

Figure 1. Expanding neck mass upon exam

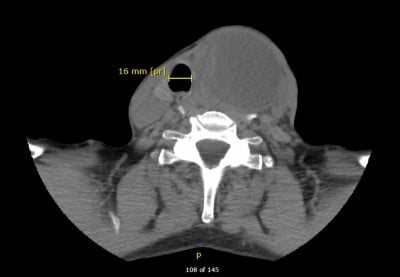

The patient was immediately taken to CT, where a CT soft tissue neck without contrast was performed. Findings of CT neck revealed a dense mass within the left lower neck arising from the left thyroid lobe compatible with a hematoma measuring 97 X 82 X 71 mm with associated rightward displacement and effacement of trachea. The greatest narrowing was below the level of the chords (Figure 2). The patient was subsequently transported to the tertiary referral center for emergent ENT evaluation due to concern for airway compromise.

Figure 2. CT imaging

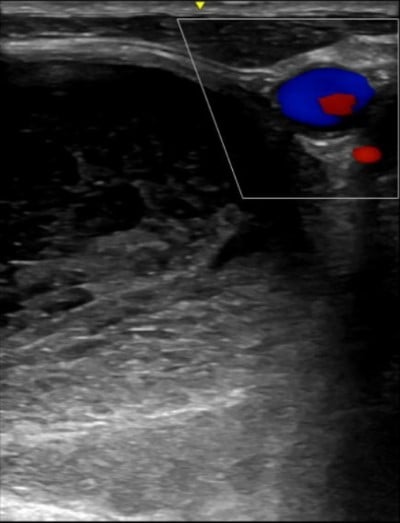

On arrival at the tertiary care center, the patient had no further expansion of the hematoma, and remained without any subjective evidence of respiratory distress. Initial evaluation included a point of care ultrasound (POCUS) to evaluate for active bleed as the initial CT scan was performed without contrast. POCUS findings revealed a well circumscribed mass with mixed echogenicity without evidence of active bleeding on color flow (Figure 3). Anesthesia and ENT were immediately consulted for co-management.

Figure 3. Ultrasound findings

After interdisciplinary deliberation, a decision was made to forgo airway management in the ED, and the patient was taken to the OR with anesthesia and ENT for intubation and clot evacuation. Anesthesia performed sedative only induction with the use of a video-assisted laryngoscope. A 5.5 reinforced endotracheal tube was passed without resistance, and a flexible bronchoscope was then utilized to ensure no sign of any significant tracheal compression. Decompression of the mass was achieved via aspiration with an 18-gauge needle, where 30 mL of pink serous fluid was evacuated with significant decompression of the swelling. No obvious venous or arterial blood was observed, and the patient was taken to the ICU intubated with plans to be extubated in the morning. Surgical cytology results of the fluid collected showed abundant bloody fluid with no follicular cells present. The patient was then taken to OR 5 days later for a thyroid lobectomy due to some smaller re-accumulation of fluid.

Discussion

Several case reports have been found on spontaneous thyroid hemorrhages. However, most cases involved the use of anticoagulation or blunt trauma to the neck. Interestingly, neither of the above are factors in this case. The literature has described some mechanisms for hemorrhage into thyroid nodules. Abnormal vascular anatomy may result in weakening of the veins or arteriovenous shunting into the nodule.6,7,8 However, even in the circumstances of abnormal vascularity or anticoagulation, hemorrhage is often linked to an inciting event such as trauma, or extreme exertion.1 Slow growth of thyroid nodules appears to be a risk factor for an acute airway obstruction if hemorrhage occurs into these nodules and is a factor in this case, as the patient noted undulating growth over 18 years.2

Many traumatic causes are due to fine needle aspiration biopsies, but usually spontaneous cases involve anticoagulation, where they do not require emergent surgery or intubation, and instead can be treated with drainage and elective thyroidectomy.3,9 Thyroidectomy also presents such risks of anterior neck hematomas and some of the risk factors include vomiting, hypertension, constipation, coagulopathies.11

The case outlined in this report contains many unique characteristics of an expanding neck hematoma:

- Spontaneous nature without clear risk factors;

- Initial presentation to a community hospital with limited ancillary resources;

- Anatomic location of the airway compromise,

Given the spontaneous nature, the source of the expanding neck mass was not immediately clear. The initial diagnostic evaluation was a non-contrast CT of the neck, and in retrospect, an argument can be made for consideration of either a CT angiogram or a CT soft tissue neck with contrast to evaluate for potential extravasation. There was a critical role for POCUS in this situation, which allowed for prompt visualization of the major blood vessels of the neck as seen in Figure 3. Further consideration should occur regarding the benefit of POCUS in the diagnostic evaluation of expanding neck hematomas, especially in time- and resource-limited circumstances.

The location of the compression was mid-trachea and well below the level of the vocal cords, causing significant displacement of the airway with a narrowing to 7 mm due to mass effect (Figure 2). This factor cannot be underestimated, as a traditional endotracheal intubation may be insufficient to secure the airway due to 1) distal nature of the compression and 2) the ultimate necessity of a rigid endotracheal tube utilized by anesthesia.

These factors, when combined, ultimately weighed heavily on the decision to defer airway management in the emergency department both from the sending facility and at the tertiary referral center. Upon arrival at the tertiary referral center, anesthesia and ENT were immediately consulted for co-management. The consensus was that for further airway compromise, the immediate plan would be to proceed to secure the airway along with immediate decompression with an 18-gauge needle or incision with a scalpel.

Case Conclusion

Delayed sequence intubation was discussed with anesthesia via video assisted laryngoscope or fiberoptic scope, but ultimately this decision was delayed until the operating room. Additional tools were made available such as a cricothyrotomy kit, however this was complicated by the anatomic variation given the tracheal deviation. POCUS was utilized to identify the cricothyroid membrane and marked with a skin marker (as seen in Figure 1) if this pathway became necessary while the patient was in the department. The decision to delay intubation proved most advantageous for patient care, but the decision must be viewed within the limitations of the uniqueness of this case.

References

- Gunasekaran K, Rudd KM, Murthi S, Kaatz S, Lone N. Spontaneous Thyroid Hemorrhage on Chronic Anticoagulation Therapy. Clin Pract. 2017;7(1):932.

- Lee JK, Lee DH, Cho SW, Lim SC. Acute airway obstruction by spontaneous hemorrhage into thyroid nodule. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(4):387-389.

- Szeto LD, Hung CT. Haemorrhage of a Thyroid Cyst as an Unusual Complication of Intubation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2002;30(2):230–233.

- Tsukahara K, Sato K, Yumoto T, et al. Soft Tissue Hematoma of the Neck Due to Thyroid Rupture with Unusual Mechanism. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:217–220.

- Lemke J, Schreiber MN, Henne-Bruns D, et al. Thyroid gland hemorrhage after blunt neck trauma: case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):115.

- Terry WI. Radium emanations in exophthalmic goiter: blood vessels of adenomas of thyroid. JAMA. 1922;79(1):1–3.

- Johnson N. The blood supply of the thyroid gland, I: the normal gland. Aust N Z J Surg. 1954;23:95–103.

- Johnson N. The blood supply of the thyroid gland, II: the nodular gland. Aust N Z J Surg. 1954;23:241–252.

- Başak H, Yücel L, Hasanova A, Beton S. Management of a Spontaneous Thyroid Nodule Hemorrhage Causing Acute Airway Obstruction. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;59(4):289-291.

- Shakespeare WA, Lanier WL, Perkins WJ, Pasternak JJ. Airway Management in Patients Who Develop Neck Hematomas After Carotid Endarterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(2):588-593.

- Gerasimov M, Lee B, Bittner EA. Postoperative anterior neck hematoma (ANH): timely intervention is vital. APSF Newsletter. 2021;36(1).

- Iliff HA, El-Boghdadly K, Ahmad I, et al. Management of haematoma after thyroid surgery: systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons and the British Association of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(1):82-95.