As a future or current emergency physician, you will frequently encounter patients presenting with back pain. A recent AHRQ review identified back pain as the fifth most common reason for visits to the ED.1

According to a meta-analysis in BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders,2 up to 17.1% of all ED visits are related to back pain. In the United States, 8 out of 10 people will experience back pain at some point in their lives,3 and of those, 5% will go on to suffer from chronic back pain.4 Back pain-related visits are also quite common in clinical settings, being the third most common reason for seeking medical care.1 This results in a staggering cost of $635 billion annually to the U.S. economy, encompassing direct medical costs, lost wages, and employer-related charges.1

However, a small percentage of these patients have a more serious underlying cause for their back pain than a simple musculoskeletal diagnosis. These presentations do not always follow a classic pattern, and providers must maintain a high index of suspicion. Among these, spinal epidural abscess (SEA) remains one of the most challenging diagnoses, especially early in the disease process. If undiagnosed, SEA carries a significant risk of disability.

So, on our next shift in the ED, when should we be more concerned? Are there certain associated conditions that should catch our attention? What are some red flag signs that warrant further workup, and how can we recognize these serious causes, especially early on, when they are the most difficult to diagnose?

Epidemiology

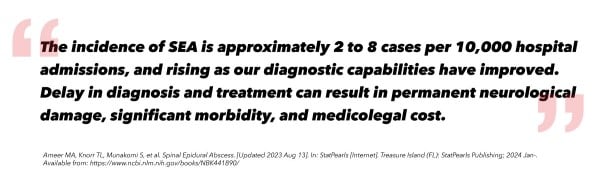

Spinal epidural abscesses can be extremely difficult to diagnose. We are taught to look for the “classic triad” of spine pain, fever, and neurologic symptoms; however, only about 10% of patients with confirmed SEA present with all three. SEA is progressive in nature, and as the abscess grows, it will impact the nerve roots and spinal cord more significantly. Thus, the later in the development of these symptoms, the more likely it is that all three “classic” signs will be present. Early on, you will face the diagnostic challenge of back pain alone and must look for risk factors to stratify patients into low, moderate, and high-risk categories. These cases are particularly challenging because, although the incidence is low, the morbidity and mortality are extremely high.

Due to the complexity and urgency of diagnosing SEA, many studies have identified key diagnostic findings to help narrow the differential and spot these elusive conditions in time to preserve the patient's quality of life.

Classic Presentation

Consider a 63-year-old male with a medical history of degenerative joint disease (DJD), psoriatic arthritis, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) who presents to the ED with worsening low back pain, fever, and inability to ambulate. One week ago, he visited the ED with complaints of chronic low back pain and later went to an outpatient clinic where he received a steroid injection in his left hip. Today, the pain is sharp, located in the left lower back and flank, and radiates to his left groin.

Understanding SEA

The rate of progression of SEA is not standard and depends on vertebral anatomy. For example, stenosis can lead to faster progression. Four stages have been described in the natural history of the disease:

- Stage 1: Back pain, fever, or spine tenderness

- Stage 2: Radicular pain and nuchal rigidity

- Stage 3: Neurological deficits

- Stage 4: Paralysis

The goal is to catch SEA before it reaches stage 4, ideally in stage 1 or 2. The mechanisms of formation and spread of SEA primarily include hematogenous dissemination (over 50%), contiguous spread (10-30%), and direct inoculation (15%). The remainder of cases are idiopathic.5

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for back pain includes musculoskeletal issues, disc-related problems, infections, and systemic conditions.

Diagnostic Workup

History and Physical Examination

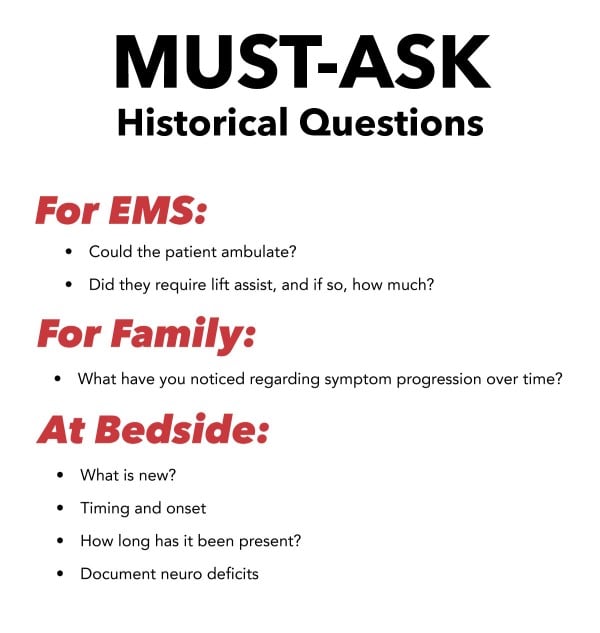

The physical exam in these patients is frequently exceedingly difficult due to pain. Additionally, many of these patients may suffer from ongoing or chronic pain from previous back surgeries or other medical issues. It is crucial to determine which symptoms, if any, are new and which are chronic. A disciplined and detail-oriented approach to the history and documentation of the physical exam is vital. This is not only important from a documentation standpoint but also helpful medicolegally. Some neurologic functions lost due to SEA may not be recovered, underscoring the importance of thorough documentation at the time of arrival.

Engage EMS in patient care, as they frequently see patients move or ambulate prior to arrival. Did the patient require assistance? Did you witness them ambulate, and if so, did they limp or stumble? Was any family present on the scene who mentioned new symptoms, trauma, fever, or recent surgery?

Work with the patient. As mentioned, these patients are often in a great deal of pain, making it challenging to obtain a detailed history. Treat their pain, then revisit the history. Ask about symptoms, onset, weakness, numbness, tingling in extremities, anticoagulant use, regular back pain, and how this episode differs.

Two key pieces of history that can be easily overlooked are recent ED visits related to these symptoms and incontinence. Patients with SEA often have a history of recent ED visits that initially seem non-specific. However, repeat visits with progression of symptoms should alert the provider. Unpack incontinence, as it can have multiple causes unrelated to SEA or cauda equina, such as stress incontinence, pelvic floor dysfunction, or mixed etiology secondary to illness like a urinary tract infection.

You will need to keep a sharp eye out for new or developing symptoms and document the timeline of symptom development and previous encounters.

When assessing a patient with back pain with SEA in mind, carefully look for the following:6

- Percuss the spinous processes for tenderness. This is important for documentation, but in the setting of worsening or progressing symptoms, lack of tenderness should not prevent further workup. Point tenderness is a red flag for infection and fracture.

- Test for saddle anesthesia by examining the sacral nerve roots. Sensation to light touch and pinprick in the perineum, posterior thigh, and perianal region is supplied by the S2-S4 dermatomes. Early in the disease process, patients may have minimal decrease in sensation.

- Perform a digital rectal exam to assess rectal tone and sensation. Document the presence or absence and any associated sensory loss.

- Assess for fever (>100.4°F) or signs of infection.

- Check for bilateral or multi-level neurologic findings in the lower extremities and assess for gait disturbances.

Inflammatory markers should be examined in the appropriate clinical setting. WBC is often not elevated and nonspecific. If clinical suspicion is high, continue with the workup despite normal WBC levels. ESR/CRP (when available) are helpful in the risk stratification process but should only be used without other ongoing inflammatory or infectious processes.5

The gold standard for diagnosing a spinal epidural abscess remains MRI with contrast. It is advised to obtain a pan view of the spine to look for skip lesions, which may occur in up to 13% of patients. Although imaging is necessary for a complete diagnosis, it is up to the clinician to decide which patients need imaging.

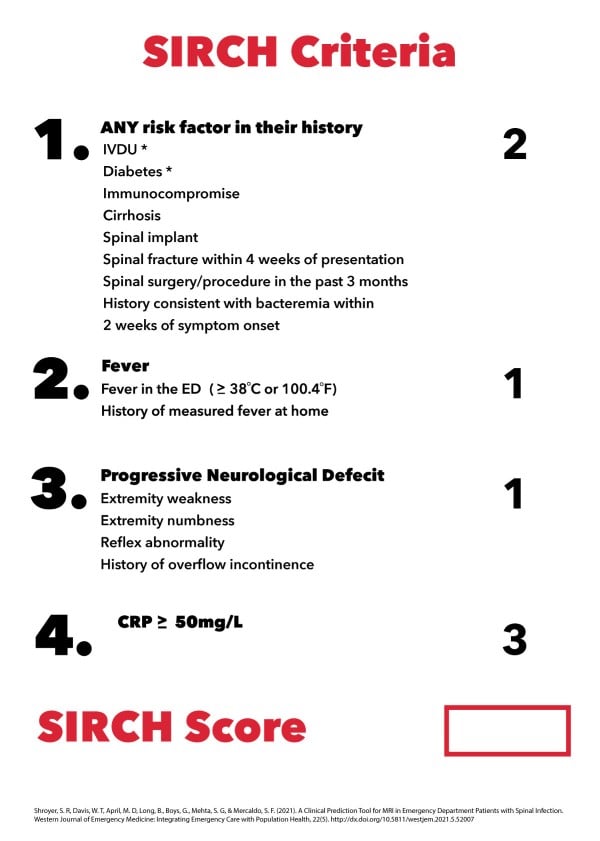

A study by Shroyer et al. in 20218 aimed to address the diagnostic challenges of spinal epidural abscesses by developing a tool called SIRCH (Spine Infection Risk Calculation Heuristic). The SIRCH assessment score can be used at the bedside to determine if the patient fits the criteria for suspected pyogenic spinal infection that requires imaging. The tool was derived from a two-part observational cohort study over six years, involving patients with low back pain. The SIRCH score uses four clinical variables to predict SEA or other spinal infections. If a patient has a SIRCH score of ≥ 3, it is best to obtain a complete spine MRI with contrast of the patient. A lower SIRCH score lowers the suspicion of a spinal abscess.

Improving the early diagnosis of spinal epidural abscesses in clinical practice involves several strategies aimed at increasing awareness, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, and ensuring timely intervention. Here are some key approaches:

Increase Awareness and Education

- Training and Continuing Education: Regular training sessions and continuing medical education programs can help increase awareness about SEA, its risk factors, and its clinical presentation.9

- Clinical Guidelines: Disseminating updated clinical guidelines and protocols for the diagnosis and management of SEA can help standardize care and improve early recognition.9

Risk Stratification

- Identify High-Risk Patients: Recognize patients with risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug use, recent spinal surgery, or immunosuppression. These patients should be closely monitored for signs of SEA.10

- Use of Scoring Systems: Implementing scoring systems like the SIRCH (Spine Infection Risk Calculation Heuristic) can help stratify patients based on their risk and guide the need for further diagnostic workup.9

Thorough Clinical Evaluation

- Detailed History and Physical Examination: A comprehensive history and physical examination are crucial. Pay attention to symptoms like severe localized back pain, fever, and neurological deficits, even if they are subtle.10

- Engage EMS and Family: Involve EMS personnel and family members in the history-taking process to gather information about the patient's symptoms and functional status prior to arrival.9

Utilize Diagnostic Tools Effectively

- Inflammatory Markers: Use inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP to aid in the risk stratification process. While these markers are not specific, they can support clinical suspicion.10

- Imaging: MRI with contrast is the gold standard for diagnosing SEA. Ensure timely access to MRI for patients with high clinical suspicion.11

Multidisciplinary Approach

- Collaboration: Foster collaboration between emergency medicine, radiology, infectious disease, and spinal surgery specialists. Early consultation with these specialists can facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment.9

- Case Discussions: Regular multidisciplinary case discussions and reviews can help identify missed opportunities for early diagnosis and improve future practice.9

Prompt Treatment and Follow-Up

- Early Intervention: Initiate appropriate treatment, including antibiotics and surgical intervention as soon as SEA is suspected. Prompt treatment can significantly improve outcomes.11

- Follow-Up: Ensure close follow-up for patients at risk of SEA, especially those with recent ED visits for back pain or those with ongoing symptoms.10

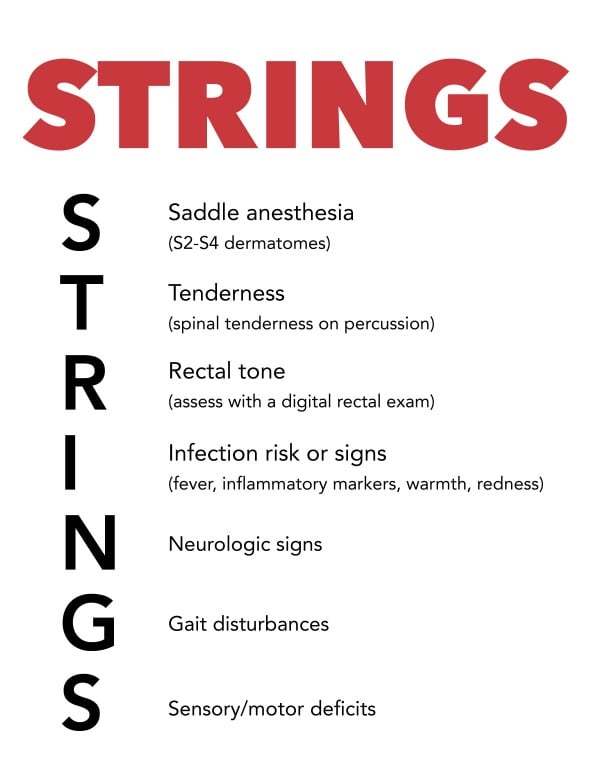

The STRINGS mnemonic can be utilized during the physical exam to fully gather all of the necessary information.

By implementing these strategies, health care providers can improve the early diagnosis and management of SEA, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.

Treatment Approaches

Discuss the multidisciplinary approach to treating SEA, involving both surgical and pharmacological interventions. Statistics on time to diagnosis versus clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

- Early detection is crucial for favorable outcomes in SEA cases.

- Maintain a heightened awareness of the classic triad and associated risk factors.

- Remember that diabetes is a major risk factor, even more so than IVDA

- A thorough differential diagnosis, including consideration of SEA, is essential in back pain cases.

- Collaborative decision-making between emergency medicine and other specialties is vital for optimal patient outcomes.

References

- Nevada Comprehensive Pain Center. Economic impact of lower back pain. 2019.

- Cai AG, Zocchi MS, Carlson JN, Bedolla J, Pines JM. Implementation of an emergency department back pain clinical management tool on the early diagnosis and testing of spinal epidural abscess. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30:995-1001.

- World Health Organization. Low back pain. 2023.

- St. Sauver JL, et al. Why do patients visit their doctors? Assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined US population. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2014.

- UpToDate. Spinal epidural abscess. (n.d.)

- Ameer MA, Knorr TL, Munakomi S. Spinal epidural abscess. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. 2023.

- Wong YN, Li HS, Kwok ST. Spinal epidural abscess: Early suspicion in emergency department using C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate tests. J Acute Med. 2023;13(1):12-19.

- Shroyer SR, Davis WT, April MD, Long B, Boys G, Mehta SG, Mercaldo SF. A clinical prediction tool for MRI in emergency department patients with spinal infection. West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(5):1156-1166.

- Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W. Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice. QJM. 2008;101(1):1-12.

- BMJ Best Practice. (n.d.). Spinal epidural abscess. Retrieved from https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/926.

- Mackenzie AR, Laing RBS, Smith CC, et al. (1998). Spinal epidural abscess: The importance of early diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1998;65(2):209-212.