Strongyloides stercoralis should be considered in any patient from a tropical climate or the Appalachian region.

Case

A 45-year-old female presents to the emergency department with 3 weeks of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and profuse watery diarrhea. The patient is originally from Iquitos, Peru, and has been visiting friends and family for the past week.

Initial vital signs are T 37.2º, HR 140, BP 90/60, Sat 95%, RR 28. On physical examination, the patient is uncomfortable and toxic-appearing, with diffuse abdominal pain and bilateral end-expiratory wheezing. CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast is unremarkable, and malaria rapid diagnostic tests, HIV, and blood smears negative.

After initiating the workup and management for sepsis, including blood, urine, and stool cultures, you admit the patient to the ICU. Comprehensive GI PCR reveals nontyphoidal Salmonella sp., and the stool exam for ova and parasite are positive for Strongyloides stercoralis rhabditiform larvae. Ivermectin is added to the broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen, and the patient begins to improve. The patient later tests positive for HTLV-1 serology and is discharged after 1 week in the hospital.

Understanding Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is an infection of the parasitic nematode, Strongyloides stercoralis. This condition is well-known in global health as a health concern among immigrants and refugees, but it is also present in many rural areas of the United States. According to the CDC, in 1 year, the Commonwealth of Kentucky had 15 strongyloidiasis-related hospital discharge diagnoses reported by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database.2

Worldwide, S. stercoralis is present in 100 million people, common in tropical South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and especially Southeast Asia.3 Death is primarily caused by the overwhelming response to the parasite in an immunosuppressed host leading to Gram-negative sepsis. In Appalachian rural areas, prevalence has been found to be up to 1.9%, even with an absence of travel to endemic countries.4 Endemic foci have also been found mostly within the southeastern states with the total number of cases in the U.S. thought to be underestimated due to subclinical infections.9

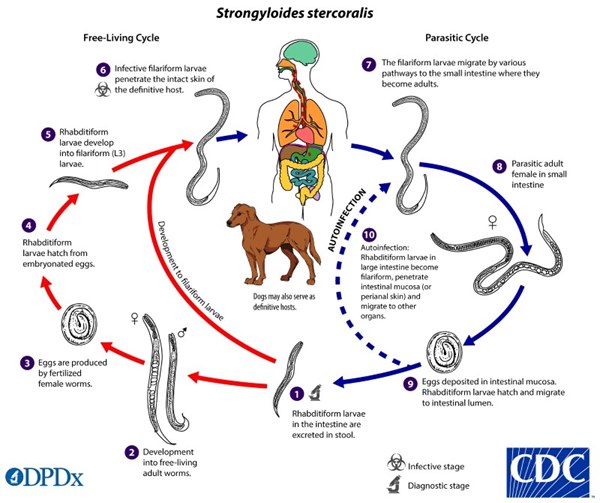

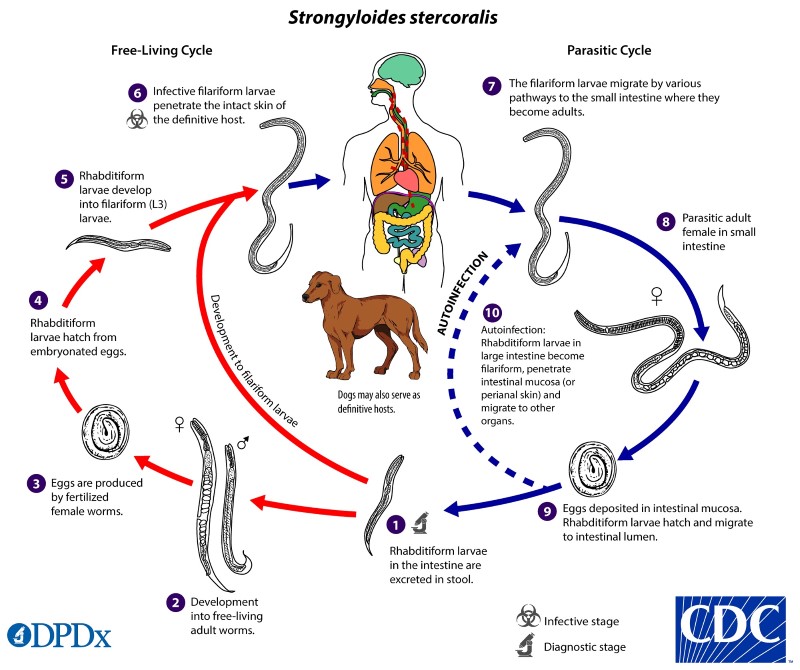

The unique life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis is worth exploring, as it is a nematode with both a free-living and parasitic life cycle - making diagnosis potentially difficult. Typically, it is transmitted when filariform larvae penetrate the skin of humans as they walk barefoot. However, it can also be transmitted through fecal-oral transmission through person-to-person contact or self-inoculation.

Once the parasite penetrates through the skin, it makes its away into the lungs via the bloodstream. Once in the lung, it irritates and activates a cough reflex which allows the parasite to be coughed and swallowed - entering the GI tract. Fecal shedding propagates the free-living rhabditiform life cycle. Rhabditiform larvae in the gastrointestinal tract can become infective filariform larvae and lead to autoinfection by penetrating the intestinal mucosa and may again disseminate to the lungs or other organs via the bloodstream.6 This repeating cycle can make diagnosis difficult, as conditions can persist many years after initial exposure without symptomatology. When should you include strongyloidiasis be on your differential? What treatments should be considered or avoided when providing emergency care for patients at risk for this condition?

Figure 2 The life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis7

Diagnosis

To determine the at-risk patient, a detailed history and physical examination should be obtained, including travel history to endemic regions, type of home sanitation system, and immunocompromising risk factors. The increase in newer immunosuppression agents in organ recipients has led to a resurgence of S. stercoralis. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is also associated with the disease. Other considerations for patients at risk for S. stercoralis according to Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease, may be the patient from “southeastern Kentucky and elsewhere in Appalachia - patients traditionally white, male, older than 50 years of age, and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.”5 Additionally, if larva currens is noted on skin examination, this would further aid in the diagnosis of this disease process.

Because strongyloidiasis can be retained throughout the host life-span, untreated chronic infections can present as chronically relapsing symptoms and patients are at risk for an overwhelming immune response if they receive corticosteroid therapy. The diagnosis of S. stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis is often difficult, as it can present decades after first exposure.

Hyperinfection can be seen as symptoms of diarrheal illness, ileus, Gram-negative sepsis, Loeffler's syndrome, meningitis, peritonitis, endocarditis, and larva currens. According to Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, "the mortality associated with untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis approaches 100%, and even with treatment it may exceed 25%.”8 Patients who present with new-onset respiratory distress with wheezing and or Gram-negative sepsis while living in or traveling to S. stercoralis endemic regions should be considered for hyperinfection/disseminated infections.

Diagnosis may be made through sputum, skin, or stool examination looking for larvae. IgG serology is also available for detecting chronic infections.8 While elevated eosinophil counts are helpful in the diagnosis of chronic infections, eosinophil levels are not diagnostic in patients with hyperinfection.6

Treatment

First-line treatment is ivermectin 200 mcg/kg by mouth, once daily for 1 day for the asymptomatic patient, or until the acute illness has resolved in the critically ill patient. For pediatric and pregnant patient populations, albendazole may be a safer option.5 Consider avoiding corticosteroid therapy in these patients unless otherwise indicated.

Take-Home Points

- Strongyloides stercoralis should be considered in any patient from a tropical climate or the Appalachian region.

- Special consideration should be made via screening questions and outpatient screening tests prior to steroid initiation, if possible.

- Empiric treatment with ivermectin, after stool studies, may be beneficial to critically ill patients on steroids or other immunocompromising agents who are at risk for hyperinfection or disseminated strongyloidiasis.

References

- CDC. Larva of nematode parasite ''Strongyloides stercoralis'' cause of strongyloidiasis. U.S. Federal Government public domain image. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strongyloides_stercoralis_larva.jpg; 2005.

- Davis S, Bosserman E, et al. N otes from the Field: Strongyloidiasis in a Rural Setting — Southeastern Kentucky, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(42):843.

- Walker P, Barnett E. Immigrant Medicine. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

- Russell ES, Gray EB, Marshall RE, et al. P revalence of Strongyloides stercoralis Antibodies among a Rural Appalachian Population—Kentucky, 2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(5):1000-1001.

- Magill AJ, Ryan ET, Hill DR, Solomon T. Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease. 9th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Strongyloides. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- da Silva AJ, Moser M. The life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis. Public Health Image Library; 2002.

- Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Saunders; 2015.

- Croker C, Reporter R, Redelings M, Mascola L. Strongyloidiasis-related deaths in the United States, 1991-2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2):422–426. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0750