James Hall, MD, Univ. of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO

Sajid Khan, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Dept. of Emergency Medicine, Univ. of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO

Case Presentation

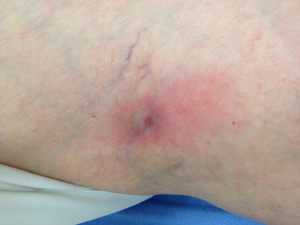

A 51-year-old female presents complaining of vague abdominal and back discomfort and a rash in her right popliteal fossa, where four days ago she noticed an embedded tick. She has not been traveling, camping, or hiking, but lives in a wooded area and owns several dogs. The rash is not painful or pruritic, but has been expanding since the day the tick was removed (Image 1). She has no fevers, chills, headache, or arthralgias. A 10-day course of doxycycline is prescribed, and close follow up is arranged. A three-week phone ED follow up reveals that she developed diffuse arthralgias and myalgias, but these resolved — along with her rash — after a few days.

Introduction

There are many diseases that are transmitted by ticks in the United States, including Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, southern tick-associated rash illness, tularemia, anaplasmosis, and ehrlichiosis, as well as the newly discovered Heartland virus, of which eight cases had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) as of March 2014.1 All of these illnesses occur almost exclusively in the summer months. Ticks naturally gravitate to protected areas of the skin: the axillae, popliteal fossae, belt line, or other skin folds. The best method of prevention is to reduce exposure. Vaccines are always in a state of development, but most have limited access and questionable benefit. Since the majority of patients don't feel any pain when they are bitten, it can be difficult to ascertain how long the bite has been present before care is sought. However, it is generally considered unlikely that a tick will transmit disease if attached for only a few hours, or if it shows no signs of engorgement. General principles of care for tick bites include removal of the tick and initiation of antibiotics (typically doxycycline), followed by supportive management. Listed here is a review of some of the more prominent tick-borne illnesses seen in the United States.

Lyme disease

According to the CDC, Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States.1 It infects approximately 20,000 people each year. The black-legged tick (Ixodes Scapularis) that transmits Lyme disease is endemic to several parts of the U.S., most notably from northern Virginia through southern Maine, as well as parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota. It has also been found on the Pacific coast, and has been reported in nearly every state. The responsible organism is the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi.

The rash of Lyme disease, termed erythema migrans, is annular in nature and extends out from the site of the bite. It typically begins 3-30 days after exposure to the tick, with the median presentation being on day seven. The tick must have been in place for greater than 48 hours for the rash to appear, though rates of transmission after 72 hours have been reported as no more than 25%.2 As per the CDC, erythema migrans is only significant when it reaches 5 cm in diameter. Though a rash is common (approximately 70% of cases), Lyme disease can also present with a wide range of vague constitutional symptoms, including arthralgias, myalgias, headache, fever, and fatigue. This makes it difficult to distinguish clinically from many of the other tick-borne illnesses that share these presenting symptoms. Testing for Lyme disease with Borrelia titers is available, but may not be helpful in the early stages of the disease, particularly if there are not significant systemic symptoms present.3 There are well-known complications and long-term sequelae, including the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, neurologic problems, facial nerve palsy, and arthritis.4 The Infectious Disease Society of America recommendations are for antibiotic treatment with doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime for 10-21 days.

STARI

Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) resembles Lyme disease in a number of ways. The appearance of the rash, timeline of the clinical course, and the presence of constitutional symptoms are all comparable. It is transmitted by the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), and some conflicting data suggests that it may be caused by the spirochete Borrelia lonestari. It is most often found on the fringes of Lyme-endemic regions throughout the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states. Recommended treatment is similar to Lyme disease; a 10-day course of doxycycline or amoxicillin is typically prescribed.5 Interestingly, patients bitten by the lone star tick may develop IgE antibodies to a specific glycoprotein found in the meat of mammals. Such patients, who may have always enjoyed consuming red meat, will present with delayed anaphylaxis 3-6 hours after eating. They will often have negative allergy skin tests, further obscuring the diagnosis. This phenomenon has been seen most frequently in the northeastern states.6

Tularemia

Tularemia can be transmitted in a variety of ways: handling of sick animals, inhaling dust particles, drinking contaminated water, and through tick bites. Ticks that transmit tularemia include the dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) the wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni), and the lone star tick. Most cases are discovered in the western states.

Symptoms depend on the method of transmission; when associated with tick bites, patients can develop either a glandular or ulceroglandular form of tularemia. Ulceroglandular tularemia is characterized by the presence of a skin ulcer and regional lymphadenopathy, which develop at the site of entry. Regardless of the method of transmission, the presence of a high fever is almost universal.

There is no spread from human to human, so isolation is unnecessary in the hospital. The treatment of choice is streptomycin for ten days.

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis is a broad term referring to several different infections. Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii are the most common disease-causing organisms, and are transmitted by the lone star tick. Infection can cause prolonged fever, chills, arthralgias, myalgias, and headache. In some cases a rash can develop, but this cannot be used to establish a diagnosis. When present, the rash may appear petechial, or may be indistinguishable from the rash caused by Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Severe clinical presentations may include difficulty breathing, and it may prove fatal if not diagnosed and treated promptly. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and can later be confirmed with specialized laboratory tests.7 Titers and PCR testing lack sensitivity and specificity. Leukopenia, elevated transaminases, and thrombocytopenia are often present. The Infectious Disease Society of America recommends treatment with 10 days of doxycycline.4 Patients who are treated early may do well on outpatient antibiotics, while those who have a more severe course may require hospitalization, intravenous antibiotics, and even intubation for respiratory support.

Anaplasmosis

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, also known as anaplasmosis, is transmitted by tick bites primarily from the black-legged tick Ixodes. It is most noticeably present in the southern and western states. Symptoms are virtually indistinguishable from ehrlichiosis and include fever, headache, chills, and myalgias.

Furthermore, co-infection with tick-borne microorganisms is being increasingly reported, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations. As for ehrlichiosis, doxycycline is the antibiotic of choice for treatment.

Babesiosis

Most cases are spread by the black-legged Ixodes tick. It is mostly found in the Northeast and upper Midwest during the warm months. Infections can range from subclinical to severe and include symptoms such as fever, body aches, and weakness. Some patients may have hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or jaundice. Severe cases may be associated with thrombocytopenia, DIC, hemodynamic instability, renal failure, and death. Diagnosis is initially made based upon clinical suspicion, but a peripheral blood smear should be ordered early ”“ presence of the protozoan Babesia parasites within red blood cells is confirmatory. Differentiating this illness from malaria may prove difficult, as both can appear very similar microscopically. The presence of ”œmaltese cross” formations is essentially diagnostic of babesiosis.8 Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment, and in mild to moderate cases a combination of atovaquone and azithromycin may be used. In severe cases, exchange transfusions may be necessary.

Heartland virus

A phlebovirus first discovered in 2012 in northwestern Missouri, cases associated with this virus have only been reported in Missouri and Tennessee. Like STARI, it is thought to be transmitted by the lone star tick. Since its discovery, there have been eight reported cases and one fatality. In addition to causing diarrhea, infection with the virus shares the constellation of constitutional symptoms with the other tick-borne illnesses: fatigue, fever, arthralgias, and myalgias. Like ehrlichiosis, it can produce findings of leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transÂaminases.

Initial cases of Heartland virus were thought to be ehrlichiosis. Little is known about the virus at this time, and there is no confirmatory lab test. Treatment consists only of supportive measures. The single fatality was an elderly man with multiple comorbidities.1,9

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

One of the most well-known tick-borne diseases, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is caused by the bacteria Rickettsia rickettsii, and it is perhaps something of a misnomer. While it was first described in the mountain states of Idaho and Montana, today the majority of cases are found not in the Rocky Mountains, but instead lengthÂwise across the nation from North Carolina to Oklahoma, with wider extension through the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic.10 It has, however, been reported in nearly all of the contiguous states, in addition to Canada, Mexico, and beyond. Similar to tularemia, the tick vector is either the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), or the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni).

Rickettsia has a propensity to infect the vascular endothelium, which then leads to microinfarcts and hemorrhages, often in the brain, lung, kidneys, liver, and spleen. While the most easily recognizable symptom of RMSF is the characteristic centripetal rash, which begins in the distal extremities, this is actually only present in about 75% of individuals. The most common findings are fevers, headaches, and myalgias, all of which are present in about 90% of patients.11 First-line treatment is with doxycycline or another tetracycline antibiotic. If needed, chloramphenicol can be used, though its side effects often limit its scope. While introduction of these antibiotics in the late 1940s greatly decreased mortality from the disease, the overall incidence has been increasing as more and more individuals are exposed in outdoor activities. Current mortality stands at about 3-5%, even with treatment.12 Like most other tick-borne diseases, the months in which RMSF is most commonly reported are May-August.

Conclusion

Many tick-borne illnesses are clinically inÂdistinguishable from one another. Symptoms are often vague, but the most common presentations include flu-like illnesses with fever, myalgias, and rash. Early recognition and treatment is of utmost importance as these illnesses can prove fatal. Most patients will notice an onset of symptoms 1-2 weeks after the tick bite is presumed to have occurred, and antibiotic treatment should begin immediately. Laboratory testing and confirmation is of limited value in the emergency department, though can help distinguish particularly difficult cases after admission.

Image 1. Circumferential rash surrounding a tick bite in the popliteal fossa.

References

- Heartland Virus. CDC cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/heartland/index.html updated March 2014.

- Nadelman RB et al. Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(2):79-84.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease - United States, 2003”“2005. MMWR 2007; 56:573-96.

- Wormser GP et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43(9):1089-134.

- Masters E, Granter S, Duray P, Cordes P. Physician-diagnosed erythema migrans and erythema migrans-like rashes following Lone Star tick bites. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134(8):955-60.

- Wolver SE et al. A peculiar cause of anaphylaxis: no more steak? The journey to discovery of a newly recognized allergy to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose found in mammalian meat. J Gen Intern Med 2013 Feb;28(2):322-5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis ”“ Maine, 2008. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep 2009; 1033.

- Krause PJ et al. Diagnosis of babesiosis: Evaluation of a serologic test for the detection of Babesia microti antibody. J Infect Dis 1994;169:923-926.

- McMullan LK et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(9):834-41.

- Openshaw JJ, Swerdlow DL, Krebs JW, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 2000-2007: Interpreting contemporary increases in incidence. Am J Trop Med Hyg (83)2010,174; Erratum 83(2010), 729.

- Helmick CG, Bernard KW, D'Angelo LJ: Rocky Mountain spotted fever: Clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological features of 262 cases. J Infect Dis 150:480, 1984.

- Paddock CD, et al:Assessing the magnitude of the fatal Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States: Comparison of two national data sources.Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002; 67:349.