Case: 9-Year-Old Female with Generalized Edema and Dyspnea

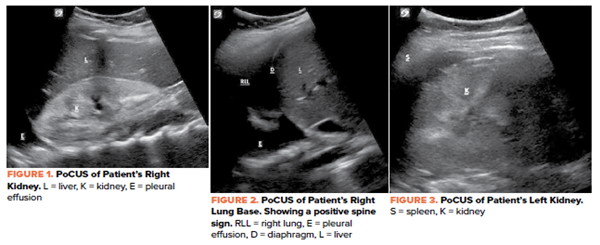

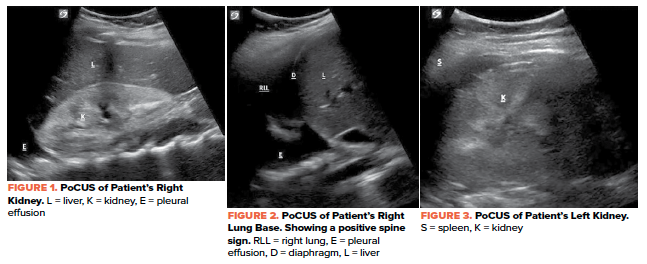

A previously healthy, fully immunized 9-year-old female presents to the emergency department with 3-4 weeks of worsening edema in her face, abdomen, and lower extremities; progressive dyspnea on exertion; and orthopnea. She has no history of fever, upper respiratory symptoms, diarrhea, or sore throat. A review of systems is otherwise negative. Physical exam demonstrates left-sided facial edema, bibasilar rales, tachypnea with subcostal retractions while supine that improves with sitting up, anasarca, and trace peripheral edema of both lower extremities. Point-of-care ultrasound was used for bedside evaluation of the anasarca and to evaluate for other possible sources of orthopnea.

Diagnosis: Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

In the ultrasound images above (Figures 1-3), the patient had demonstrated hyper-echogenicity of both kidneys suggestive of medical renal disease. In addition, the ultrasound discovered bilateral pleural effusions that ultimately required diuretic therapy. The patient was found to be hypertensive to the 150s/90s and was treated with isradipine in the emergency department.

Labs and urine studies revealed an acute kidney injury (creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL), proteinuria (5,486 mg/L) with an elevated urine protein to creatinine ratio (9.6 mg/mg), hypertriglyceridemia (622 mg/dL), hypoalbuminemia (2.7 g/dL), hyperparathyroid (108.3 pg/mL), normal C3 and C4, and a normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 7.3 g/dL, MCV 82.9 fL). Biopsy of the left kidney revealed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) with scarring, mild tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. The patient was discharged on hospital day three with amlodipine for blood pressure management and prednisolone for FSGS.

Ultrasound Review: Renal Ultrasound

PoCUS can be used to help evaluate patients with suspected kidney pathology and to diagnose causes of renal colic, renal failure, hematuria, and decreased urine output. Compared to computed tomography (CT), ultrasound can result in shorter lengths of stay, lower cost, and improved safety. Renal ultrasound is becoming more popular as the initial test in the evaluation of suspected nephrolithiasis and renal colic. There are a few dilemmas involved in utilizing renal ultrasound to diagnose nephrolithiasis since ultrasound is not accurate in predicting stone passage and, unlike CT scan, does not evaluate other causes of flank pain.

Technique

To perform a renal ultrasound, a curvilinear transducer should be used for optimal axial and lateral resolution. Each kidney should be scanned in 2 planes: longitudinal and transverse. Physicians can quickly assess for medical renal disease on both sides using a standard RUQ (Morrison’s Pouch) window as well as a standard LUQ (splenorenal) window. Remember, the left kidney is more posterior and superior. Color and Doppler modes can be utilized to differentiate between vascular and non-vascular structures such as hydronephrosis, and for blood flow restriction as patients with nephrotic syndrome are at higher risk for coagulopathy including renal vein thrombosis.

- For the right kidney: Place probe on the patient’s right side along the mid-axillary line at the most intercostal space with probe marker initially pointing towards the head. The probe should be rocked from superior to inferior pole of the kidney and fanned from anterior to posterior to evaluate the entire kidney. After the longitudinal view is obtained, the probe marker should be oriented anterior to create the transverse view of the kidney. The probe should be fanned again superior to inferior to visualize the entire kidney. Slide the probe towards the head to visualize the diaphragm to evaluate for fluid above the diaphragm.

- For the left kidney: place the probe initially over the posterior axillary line at the second most inferior intercostal space. The probe marker should be oriented towards the patient’s head and then anteriorly.

TIP#1: For the left kidney, the knuckles should be touching the cot for optimal views.

TIP#2: Having the patient take breaths in and holding (briefly) may allow for the structures to come into better view as well.8

Check out these videos for a walkthrough of the renal ultrasound:

3D How To: Left Kidney Ultrasound - SonoSite Ultrasound

Check out these videos for a walkthrough of a pleural effusion: https://www.coreultrasound.com/pleural-effusions-part-1/

https://www.coreultrasound.com/pleural-effusions-part-2/

Take-Home Points

- FSGS is a major cause of morbidity stemming from the many proteins that are lost in the urine (eg, albumin creating pleural effusions, immunoglobulins causing an immunocompromised state, and antithrombin inducing a coagulopathic environment).

- Physicians can quickly assess both kidneys for sonographic patterns such as changes to the parenchymal echogenicity, corticomedullary differentiation, and renal size as possible indicators that the nephrotic syndrome is more complex than minimal change disease.

- Remember to always evaluate both kidneys in both longitudinal and transverse axis.

- Having the patient take breaths in and holding (briefly) may allow for the structures to come into better view.

- If there is concern for renal colic or nephrolithiasis, consider scanning the bladder as well.

- Consider scanning above the diaphragm as well when assessing the kidneys to look for pleural effusions.7,8

References

- Park SJ, Shin JI. Complications of nephrotic syndrome. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54(8):322–328.

- Vande Walle JG, Donckerwolcke RA. Pathogenesis of edema formation in the nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001 Mar;16(3):283-93.

- Salame H, Damry N, Vandenhoudt K, Hall M, Avni FE. The contribution of ultrasound for the differential diagnosis of congenital and infantile nephrotic syndrome. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(12):2674-9.

- Daneman A, Navarro OM, Somers GR, Mohanta A, Jarrín JR, Traubici J. Renal pyramids: Focused sonography of normal and pathologic processes. Radiographics. 2010;30:1287-1307.

- Faubel S, Patel NU, Lockhart ME, Cadnapaphornchai MA. Renal Relevant Radiology: Use of Ultrasonography in Patients with AKI. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014; 9(2): 382-394.

- Dawson M, Mallin M. Introduction to Bedside ultrasound: Renal. Emergency Ultrasound Solutions; 2011; 1:109-124.

- Ahmed AA, Martin JA, Saul T, Lewiss RE. The thoracic spine sign in bedside ultrasound. Three cases report. Med Ultrason. 2014 Jun;16(2):179-81.

- Chichra A, Makaryus M, Chaudhri P, Narasimhan M. (2016). Ultrasound for the Pulmonary Consultant. Clinical medicine insights. Circulatory, respiratory and pulmonary medicine, 10, 1–9.