Case

A 77-year-old male with coronary artery disease, diabetes, and a recent left femoral neck fracture is sent to the ED for non-resolving decubitus ulcers despite antibiotic treatment and wound care. He complains of severe pain to his lower back and scrotum. He is afebrile, but tachycardic. He is found to have a large stage 4 sacral decubitus ulcer with an eschar near the anus, but a swollen, erythematous, and foul-smelling scrotum with streaking gray necrotic tissue.

Questions to consider:

- What is the differential diagnosis?

- What diagnostic studies would you perform?

- Would point-of-care bedside ultrasound help in this case and if so, what are you looking for?

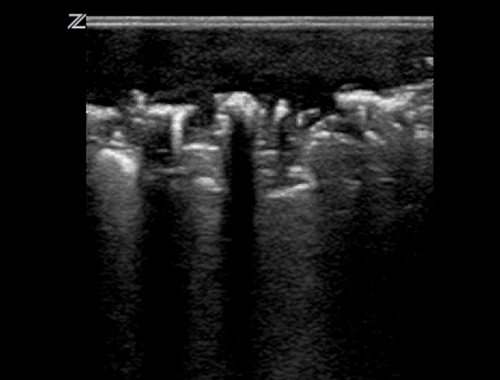

A bedside ultrasound reveals gas in the soft tissues of the scrotal wall (Image 1). He is immediately started on fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics, and within the hour is taken to the OR for debridement. After several bouts with septic shock and return trips to the OR, he is transferred to a long term nursing facility.

Discussion

This patient presented with necrotizing fasciitis of the scrotum, also known as Fournier's gangrene. The clinical suspicion was heightened by visualization of gas on ultrasound.1 Fournier's gangrene is primarily a clinical diagnosis, with the gold standard being direct evaluation of affected tissues in the operating room. Risk factors that predispose patients to necrotizing soft tissue infections typically include immunocompromised states (including alcoholism), chronic heart disease, old age, diabetes, malignancy, and pre-existing decubitus ulcers.2

Dr. Fournier, a French venereologist, first described Fournier's gangrene in 1883 as an idiopathic process, but it has since been understood to be a synergistic polymicrobial infection of the subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia involving the genitalia and perineum.3,4 Fournier's gangrene carries a high mortality rate of 33-40%, with fascial necrosis spreading as rapidly as 2-3 cm per hour, making this a highly time-sensitive diagnosis.4,5 Salient features that differentiate this life-threatening necrotizing soft tissue infection from cellulitis include pain out of proportion to exam, rapidly spreading infection, and malodorous discharge. But above all, the pathognomonic factor is gas within the tissue.3

Palpation of crepitus on exam is very specific, but neither sensitive nor reliable, with its presence ranging from 19-64% of cases.3,5,6 X-ray evaluation of gas within the tissue is more sensitive than clinical exam, but still suboptimal with sensitivity up to 89%.3-4,6 CT/MRI of the soft tissue is much more sensitive in detecting gas but is time consuming, requires the patient to leave the clinical care area, and requires administration of intravenous contrast. As patients presenting with symptoms consistent with Fournier's gangrene are often unstable and have concomitant acute kidney injury from systemic disease, having the patient leave the resuscitation area and delaying time to definitive treatment in order to obtain CT or MRI is not ideal. Further, administration of IV contrast can worsen pre-existing renal insufficiency that is often seen in these patients with multiple co-morbidities.5

Bedside ultrasound allows patients to stay in the clinical care area, which is more convenient for resuscitation. It is rapidly performed at the patient's bedside, yields immediate results, and is more sensitive than X-ray.3,4 Of note, Kane, et al detected gas in soft tissue using ultrasound in all studied patients without crepitus, and Butcher, et al also found a 100% sensitivity of ultrasound to detect soft tissue air.1,3

A high-frequency (7-12 mhz) linear probe should be used to evaluate the skin and subcutaneous tissue (Image 2).7 In normal tissue, the epidermis and dermis appear as thin hyperchoic linear structures superficial and parallel to the subcutaneous tissue, which contains hypoechoic adipose tissue banded by hyperechoic linear connective tissue septa. In cellulitis, subcutaneous tissue becomes edematous, creating increased hypoechoic spaces between fat globules. More advanced cellulitis has increased fluid accumulation between islands of adipose tissue, creating the classic “cobblestone” appearance (Image 3).

Necrotizing gangrene commonly contains gas produced from by-products of bacterial metabolism.3 The scrotal wall will be thickened from edema with scattered foci of gas. The testis and epididymis, if visualized, are generally normal in appearance. Gas on ultrasound appears as high amplitude, bright, hyperechoic beams with posterior scattered acoustic shadowing and can often obscure underlying structures such as the testis (Image 1).1-7

Not all gas found in the scrotal sac indicates Fournier's gangrene.7 Air found deep to the subcutaneous tissue layer could be from loops of trapped bowel.7 It is important to discern the origin of air foci in order to avoid diagnostic error.

Once Fournier's gangrene is diagnosed or highly suspected, the patient should be started on broad spectrum antibiotics covering gram positive organisms (including MRSA), gram negatives, and anaerobic bacteria. Consultation with surgery should occur immediately, as definitive treatment of Fournier's gangrene and other necrotizing soft tissue infections is expedited surgical debridement.

References

- Butcher CH, Dooley RW, Levitov AB, Detection of subcutaneous and intramuscular air with sonography: a sensitive and specific modality, J Ultrasound Med 2011 Jun:30(6):791-5.

- Cainzos M, onzalez-Rodriguez FJ, Necrotizing soft tissue infections, Curr Opin Crit Care 2007 Aug;13(4):433-9.

- Kane CJ, Nash P, McAninch JW, Ultrasonographic appearance of necrotizing gangrene: aid in early diagnosis, Urology 1996 Jul;48(1):142-4.

- Kim D, Kendall JL, Fournier's gangrene and its characteristic ultrasound findings, J Emerg Med 2013 Jan;44(1):e99-101.

- Kube E, Stawicki SP, Bahner DP, Ultrasound in the diagnosis of fournier's gangrene, Int J crit Illn Sci 2012 May-Aug;2(2):104-106.

- Morrison D, Blaivas M, Lyon M, Emergency diagnosis of Fournier's gangrene with bedside ultrasound, Am J Emerg Med 2005 Jul:23(4):544-7

- Wright S, Hoffmann B, Emergency ultrasound of acute scrotal pain, Eur J Emerg Med 2015 Feb;22(1):2-9.