Among U.S. hospitals, the proportion of leadership roles occupied by medically trained professionals is decreasing. But it's important to have physicians in administration - so it's important for residents to add administrative and operations skills to their repertoire.

In the thousands of U.S. hospitals, only 3-5% of hospital leaders are physicians.1,2 This is a change in paradigm from the historical origins of establishing hospital systems. Originally, hospitals were founded by physicians with the help of wealthy and influential sponsors; fast forward more than a hundred years, and the trend of health care physician leaders has moved in the opposite direction. More hospitals are opening and the physician workforce is increasing, but the proportion of leadership roles occupied by medically trained professionals is decreasing.3

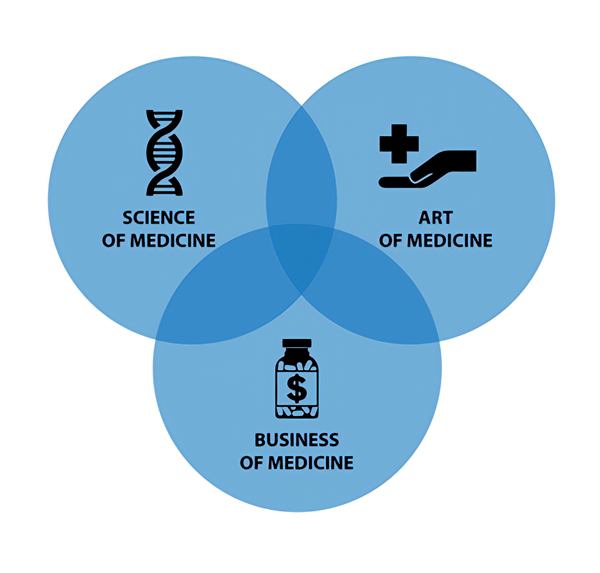

The importance of the business of medicine becomes more apparent as we move farther into our medical careers. Medical practice is a triad of science, art, and business, and in our pursuit of improving the world through medicine, we gain understanding of all three. We spend 4 years in medical school learning the science of medicine and 3+ years in residency to master the art of clinical practice, but we receive little education on operational practice.

In residency, exposure to ED operations management, business administration, patient safety, and quality improvement is frequently limited to eye-roll-inducing Press Ganey scores, metrics of patients per hour, or sepsis bundle checklists. One could easily argue against the utility of some of these metrics. Notably, an interesting nuance of Press Ganey scores is that they are only recorded for patients who are discharged from the ED. This represents a flaw, as those patients have lower acuity and thus endure longer wait times and receive the least attention (both associated with poor Press Ganey scores) while attention and time are devoted to critical patients fighting for survival.4 Hence, other methods of measuring the satisfaction of patients treated by emergency physicians, such as Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care, are currently being pursued.5

Simple metrics such as patients per hour are also not without problems. For example, a normal patient with absolutely no pathology might actually require more time and resources of an ED — extended monitoring, thorough diagnostic testing for atypical presentations, and repeat examinations, in order to determine if the patient is safe for discharge. Contrast this with a sicker patient, such as a triageidentified STEMI, who would be in and out of the ED on their way to a cardiac catheterization lab within minutes. Similarly, the safety of the sepsis bundle, which mandates that patients receive a 30 cc/kg fluid bolus and early broad-spectrum antibiotics, is being questioned, as not all that triggers SIRS criteria is bacterial infection.6 Numbers such as these are placed on spreadsheets and are then connected to compensation rates, such as CMS reimbursement, to affect clinical practice.7

Without having on-the-ground clinical experience, non-medical professionals in the boardroom can have difficulty understanding the intricacies of working at the bedside. Early exposure to such operational dilemmas during residency trains us to balance guidelines aimed at the population level with the reality of serving patients on the front line.

Same Skills, Different Applications

Emergency physicians practice business skills and principles on a daily basis without recognizing them as such, perhaps because it's framed in medical terminology rather than business terminology. For instance, the phrase "negotiating a contract" seems foreign and daunting considering we never negotiated a salary for residency or bargained the tuition for schooling, but we employ the concepts of negotiation every day in the department. We conduct shared decision-making to develop disposition plans with consultants, families, and patients; to phrase it another way, we "negotiate the terms" of safe discharge in order to develop a plan of care in which all parties are in agreement. Another foundational example that we practice routinely: when we call radiology to bump a critical, time-sensitive patient up first for imaging, such as a stroke protocol potential thrombolytics candidate patient, in business terms, we are allocating resources and leveraging the assets of the department.

Many administrative issues can be alleviated through similar problemsolving analytical reasoning strategies that we have been developing through the years. During winter, many EDs suffer from boarding, which is a known phenomenon that increases morbidity.8 Is there someone in the waiting room who isn't being seen immediately because of the lack of bed availability who might undergo unrecoverable pathological damages in the next hour while waiting? Framing this issue as an attending at our institution likes to put it, boarding is essentially a congestive heart failure exacerbation of the hospital; the solution is to diurese the hospital floor census and prevent flash pulmonary edema of the ED.

Developing operational and business competency is an integral element of residency training. With thousands of hours of training to develop clinical acumen, we can manage life-altering complex medical issues such as severe traumatic brain injury flawlessly, but when it comes to managing complex financial issues that affect patients in the ED, we are sometimes underprepared. From a quantitative perspective, a small ED can produce annual revenues of $1 million; similarly, helping to run a large ED means being responsible for the operations of a business that could be producing $10 million of revenue per annum.9 Being involved in these managerial decisions and optimizing health care is our obligation to our patients.

Where to Learn Administrative Skills

There are many outlets and opportunities to get involved and gain further proficiency during residency training. Depending on program curriculum, residents can choose to complete an administrative elective rotation and run their own project to solve a problem identified in their department. Residents can also learn about a broad range of topics by attending courses and conferences at a local, regional, or national level. One such conference is the Emergency Department Directors Academy (EDDA), sponsored by ACEP, a development course to introduce medical directors and physicians to the foundations of managing an ED. Dr. Robert Strauss, the chief editor Strauss and Mayer's Emergency Department Management and program chair of the EDDA, stated, "It would be wonderful if more residents took advantage of the opportunity to attain leadership skills along with the medical directors who attend. We have the best of the best among EM leadership educators, and they are passionate in their desire to share these skills." Residents can apply for a travel scholarship through EMRA to travel and attend this conference for free.

Residents can also get involved on national resident committees, such as EMRA's Administration and Operations Committee, which furthers resident interest in the subject and encourages residents to add operational management to their fund of expertise. It is imperative that we as residents focus on being excellent clinicians but to the exclusion of other facets of medicine. Learning about strategies of running an effective ED, addressing the needs of the department, negotiating patient interests, and dealing with complex departmental issues all lead residents to develop leadership skills. Through the business of medicine, we can fulfill the physician's oath to do right by our patients and become the best physicians we can be.

References

1. Kaplan AS. Climbing the ladder to CEO part II: leadership and business acumen. Physician Exec. 2006;32(2):48-50.

2. Becker's Hospital Review. The Case for Physician CEOs. http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/the-case-for-physician-ceos.html. Published March 2, 2015. Accessed January 8, 2019.

3. Falcone R, Satiani B. Physician as Hospital Chief Executive Officer. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2008;42(1):88-94.

4. Handel D, French L, Nichol J, Momberger J, Fu R. Associations Between Patient and Emergency Department Operational Characteristics and Patient Satisfaction Scores in an Adult Population. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(6):604-608.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care (EDPEC) Survey ED. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/CAHPS/ed.html. Published September 12, 2018. Accessed January 10, 2019.

6. Farkas J. PulmCrit: Top 10 problems with the new sepsis definition. EMCrit Project. http://emcrit.org/pulmcrit/problems-sepsis-3-definition/. Published June 4, 2017. Accessed January 10, 2019.

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital HCAHPS: Patients' Perspectives of Care Survey. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/hospitalHCAHPS.html. Published December 21, 2017. Accessed January 10, 2019.

8. Gaieski D, Agarwal A, Mikkelsen M et al. The impact of ED crowding on early interventions and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(7):953-960.

9. Strauss RW, Mayer TA. Strauss and Mayers Emergency Department Management. New York: McGraw-Hill Education Medical; 2014.