Emergency medicine (EM) residency exposes trainees to the informal curriculum of practice management. Through the Kern model of curriculum development, we present a national targeted needs assessment of EM residents and attendings to guide the development of future business of EM curricula.

Author contributions: All authors were involved with developing the concept and design for the study. Dr. Cozzi and Dr. Jarou were involved with data acquisition. Data analysis was performed by Dr. Jarou. All authors were involved with interpretation of the data. Dr. Cozzi was primarily responsible for drafting the manuscript, along with Dr. Jarou and Dr. Messman. All authors were involved with manuscript revision.

ABSTRACT

Methods

This study was an observational, cross-sectional online needs assessment of EM residents and attending physicians. Respondents were asked to rate their perceived current knowledge, the importance of multiple administrative and practice management topics, and to identify barriers to learning and preferred learning modality.

Results

We received complete responses from 193 residents and 232 attendings. 89.5% of respondents indicated that learning about business topics during residency is "important" or "very important" with no significant difference between residents and attendings (p=0.601). A majority of residents (61%) stated their residency program does not prepare graduates for EM practice management challenges outlined in the topics below. The preferred learning method for residents was "self-paced online learning" (25%). There was a statistically significant, moderate correlation between the essential nature of a topic as rated by attendings and resident desire to learn more (r=0.57; 95%CI 0.17 to 0.81).

Conclusion

Learning business and administrative topics is regarded as very important during residency, yet the majority of EM residents report low levels of knowledge and preparation, and many faculty do not feel like they have content expertise. Based upon this targeted needs assessment, there is an opportunity to create a national, self-paced, online, case-based EM business and administrative curriculum.

INTRODUCTION

EM residency training requires the acquisition of vast amounts of medical knowledge and procedural skills necessary to skillfully diagnose and treat acute, undifferentiated patients of all ages and walks of life. However, beyond becoming clinically excellent, EM residents are also expected to learn about practice management topics such as billing and coding, resource utilization, reimbursement, risk management, operations management, patient flow, patient experience, quality and safety. Awareness of and competency in non-clinical, practice management issues is essential for career success.1 Both the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of EM (ABEM) codified these components of the curriculum through the ACGME’s mandated integration of systems-based practice competencies into resident milestones2,3 and inclusion in ABEM’s Model of the Clinical Practice of EM, a framework for the core content of the specialty of EM.4

Prior studies of young physicians have shown that while the majority felt residency prepared them to practice medicine, very few felt prepared to manage business aspects related to practicing medicine.5 Many attending physicians believe that inclusion of practice management skills during residency would lead to increased initial success post-residency.6 While the amount of time EM residencies dedicate to education on documentation, coding, and reimbursement has slowly increased over recent decades, many residents still spend less time learning these topics than the length of a single clinical shift during their entirety of their residency training.7 Inadequate knowledge of EM practice management issues may place residents at a competitive disadvantage in the workplace and when searching for post-graduation employment opportunities given the increased competition.

Curricula for teaching the business of EM have previously been created and implemented at some EM residency programs.8,9 The widely-known Kern model of curriculum development emphasizes that planning educational experiences is a multi-step, iterative process involving:10

- Problem identification and general needs assessment

- Targeted needs assessment

- Goals and objectives

- Educational strategies

- Implementation

- Evaluation and feedback

The objective of this study is to perform a national, targeted needs assessment of EM residents and attendings to guide the development of future business of EM curricula. We will explore the current state of EM practice management education during residency training, perceived barriers to implementing this curriculum, and preferred modalities for learning this type of content moving forward. More specifically, for multiple administrative topics, we will describe current self-reported knowledge, perceived importance, and interest in learning more.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was an observational, cross-sectional needs assessment deemed Institutional Review Board (IRB)-exempt by the <<blinded for submission>> IRB (2019-641). The survey was first piloted with members of the Administration/Operations and Research Committees of the Emergency Medicine Residents' Association (EMRA), as well as with two individual residency programs with subsequent minor revisions in the language and format of the survey. Survey design was optimized using expert insight from national emergency medicine research fellowship directors. Survey responses were collected using SurveyMonkey (San Mateo, CA). Respondents who submitted incomplete surveys were excluded. Results are reported in accordance with STROBE Guidelines.11

Study Setting and Population

Unique survey links were sent to current resident members of EMRA (6537) in December 2019 with no financial or any other kind of incentives for completion. One reminder email was sent via these unique links. A faculty-specific needs assessment was also created and distributed on engagED (the online community of the American College of Emergency Physicians) and the listservs of 40 departments of EM, the Council of Residency Directors in EM (CORD), and three state chapters of the American College of Emergency Physicians (Michigan, Texas, and Illinois) due to ease of access.

Measurements and Key Outcomes Measures

Demographic information collected for resident respondents included their EM residency program, graduation year, age, gender, and ethnicity. Demographic information about faculty respondents included the name of the residency program they attended as well as current residency program affiliation (if applicable), job title, and year of residency graduation. Both groups were questioned as to whether they possessed additional business or administrative training such as an advanced degree, completing a short-course, or being involved with local or national committees.

All respondents were asked to rate their general knowledge of business in EM concepts, what importance they place on learning these concepts during residency, perceived barriers to providing business/administrative education to EM residents, as well as details about any current administrative education currently in-place at their residency programs. Additionally, residents were asked to rate how interested they would be to learn more about 20 proposed administrative and business topics, while faculty were asked to rate how essential they considered each of these topics to be, both using a 5-category Likert scale. Topics were generated from pilot study at one author’s residency program. Lastly, respondents were asked to rate the learning modalities that they would consider most effective to learn these concepts. Copies of both the resident and faculty needs assessment can be found as supplemental files.

Data Analysis

For each topic, we calculated the proportions of residents who self-identified as having below-average knowledge and above-average resident interest in learning more, as well as the proportion of attendings that rated each topic as essential. Summary statistics describing the marginal distribution of responses for all survey questions were computed. Comparisons between categorical variables were evaluated using the Chi-square test. Comparisons between resident and attending perceptions regarding topic importance were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data analysis was performed using RStudio version 1.2.5001 running R version 3.5.1.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

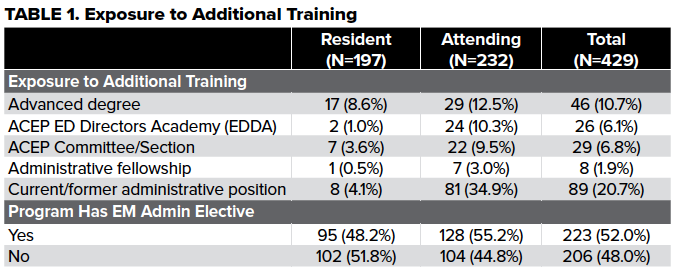

The survey invitation email was opened by 3158 residents, 291 of whom clicked through to the survey, and 207 of whom responded (6.6% response rate). There were 254 faculty respondents. Fourteen resident and 22 faculty surveys had to be excluded due to incomplete responses, leaving 193 and 232 resident and attending responses, respectively. Resident respondents were 64% male and 32% female. Two-thirds of residents (67.5%) were at 3-year residency programs, while 32.5% were at 4-year residency programs. Residents were 31% PGY1, 30% PGY2, 30% PGY3, and 6% PGY4 and represented 132 unique residency programs. The majority of attending respondents worked primarily in academic settings (55.6%), followed by 26.3% primary community and 18.1% mixed settings. The median residency graduation year of attending respondents was 2007 (IQR 2002-2014). Approximately half of respondents reported training or working at a program with an EM administrative residency elective. Many respondents reported exposure to administrative topics outside of residency training (see Table 1 for further details).

Main Results

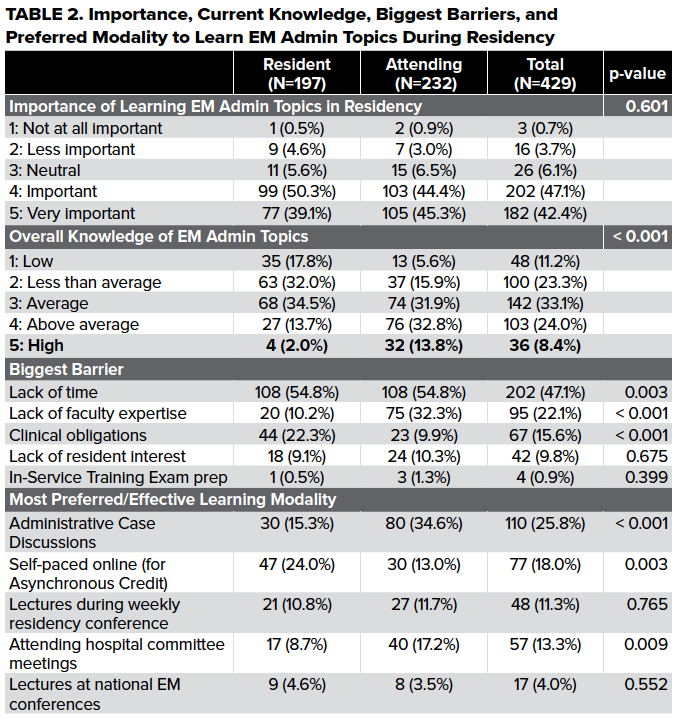

Overall, 89.5% of respondents indicated that learning about business and administrative topics during EM residency is "important" or "very important" with no significant difference between residents and attendings (p=0.601). 49.8% of residents rated their knowledge of these topics as below average, compared with only 21.5% of attendings (p<0.001).

A majority of residents (61%) stated their residency program does not prepare graduates for EM administrative challenges, though residents at programs with administrative electives feel more prepared than those at programs without electives, 47% vs 19% respectively (p<0.001).

"Lack of time" was the top barrier identified to the administration of a business of EM curriculum during residency by both residents and attendings at 58% and 40%, respectively. The second-largest barrier identified by attendings was "lack of faculty expertise" (33%); however, residents were significantly less likely to cite this as a barrier (10%, p<0.01). The most preferred learning method for residents was "self-paced online learning" (25%), followed by "administrative case discussions" (17%) whereas the most preferred from the attending perspective was "administrative case discussions" (35%), followed by "attending hospital committee meetings" (17%).

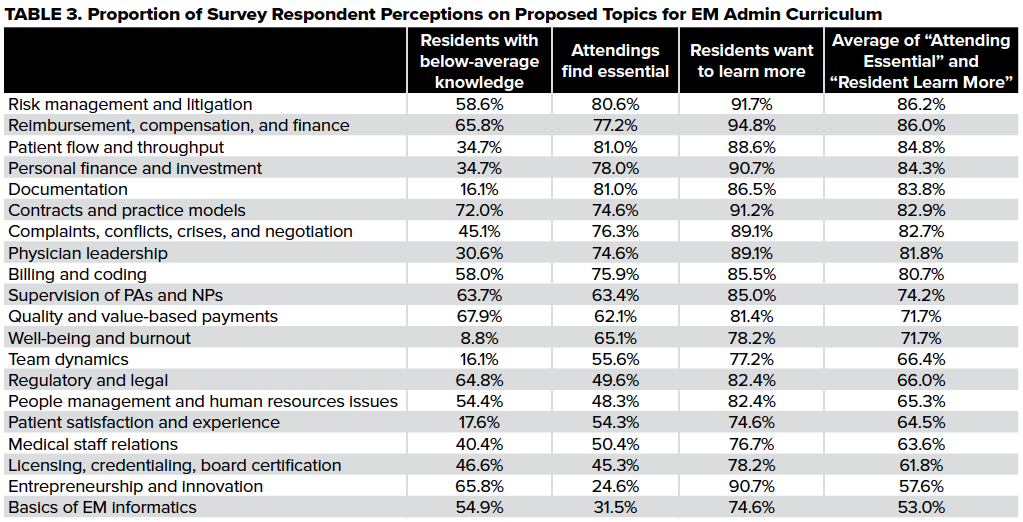

Residents were interested in learning more about all topics (range 75-95%), whereas attendings had a much broader range of what they considered essential (range 25-81%). Attending physicians found "documentation" and "patient flow/ throughput" as the two most essential topics (81% and 81%, respectively) while residents stated their desire to more fully learn these topics as: 87% vs. 89%, respectively. Sixty-eight percent of residents reported below-average knowledge of "quality and value-based payments (QVBP)" with an associated 81% of residents desiring more education in this topic, and 62% of attendings regarded this topic as essential. Sixty-six percent of residents stated their knowledge of "reimbursement, compensation, and finance (RCF)" was below average, with 95% of residents desiring to learn more and 77% of attendings finding this topic essential. Finally, the largest percentage of residents stated "contracts and practice models" as an area of below-average knowledge (72%) with 91% of residents desiring more education and 75% of attendings finding this topic essential. The topic of highest weighted average of that which attendings find essential and residents desire knowledge was "risk management of litigation (RML)", with the lowest being "EM Informatics (Informatics)" at 53%.

Using an equally weighted composite of desire to learn and essential nature of topics, the top 10 topics included: risk management & litigation; reimbursement; operations; personal finance; documentation; contracts and practice models; complaints, crisis, conflict, and negotiation; physician leadership; billing and coding; and oversight of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) (range 74-86%).

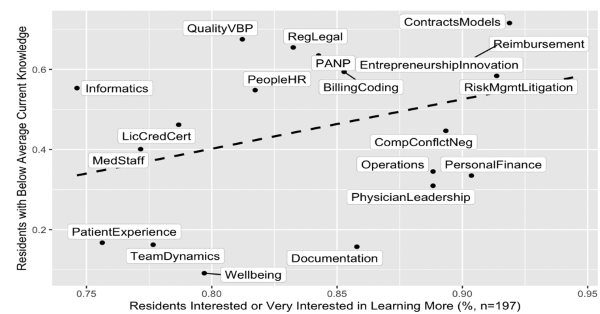

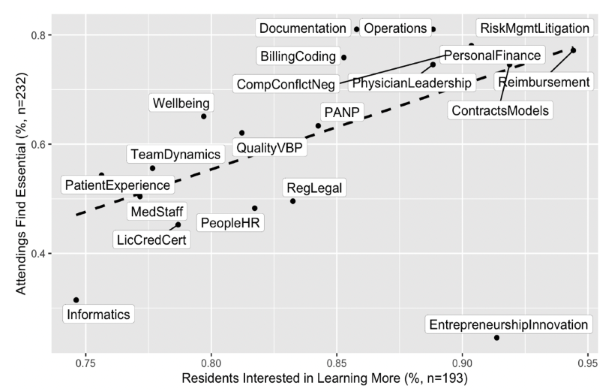

Correlation between below-average knowledge and the desire to learn more was not significant (r=0.37; 95%CI -0.07 to 0.71). There was a statistically significant, moderate correlation between the essential nature of a topic as rated by attendings and resident desire to learn more (r=0.55; 95%CI 0.17 to 0.81). The two most significant outliers between resident interest and attending physicians' rating as essential included: entrepreneurship and innovation (91% vs 25%, respectively) and basics of informatics (75% vs 31%, respectively).

FIGURE 1. Weak Positive Correlation Between Current Resident Knowledge of EM. Admin Topics and Interest in Learning More (r=0.37; 95%CI -0.07 to 0.71)

FIGURE 2. Moderate Positive Correlation Between Resident Interest in Learning More About EM Admin Topics and Attendings Finding Topic Essential (r=0.55; 95%CI 0.17 to 0.81

DISCUSSION

Both residents and attendings find learning EM admin topics during residency to be important, yet they continue to be insufficiently taught. This is consistent with findings from multiple other residency specialties, including family medicine,12,13 internal medicine,14 anesthesia,15 obstetrics/gynecology,16 otolaryngology,17 psychiatry,18 pathology,19 and general surgery20,21 which have all indicated a need for, and current deficiencies in, practice management education during residency training.22 It has been further proposed that management skills should be made a core component of medical education prior to residency to improve healthcare delivery systems and to develop a pipeline of physician leaders.23 While the percentage of medical school graduates completing dual Medical Doctor/Master of Business Administration (MD/MBA) degree programs increased by 50% between 2015 and 2019, still only 0.9% of medical school graduates pursue this route.24

Both residents and attendings cite lack of time as the most common barrier to teaching administrative topics, as has been previously described.25 Surprisingly, a significant proportion of EM attendings cite lack of faculty expertise as a barrier, suggesting that there may be a role of a national curriculum to deliver this content that may not be able to be delivered locally.

Attending physicians most preferred learning EM administrative topics through administrative case discussions and by attending hospital committee meetings, while residents most preferred learning through self-paced online modules that could be completed for asynchronous conference credit. Given the time constraints and clinical obligations of completing residency, it is not surprising that residents are in favor of an asynchronous learning option. This provides both short- and long-term flexibility that allows residents to learn at their own pace, avoid missing content that is only delivered once during their training due to a scheduling conflict, and also allows residents who are earlier in residency to focus on becoming clinically excellent, while allowing residents later in training to tackle this non-clinical curriculum once they feel comfortable with their clinical knowledge. However, online-based modules would have to be high-quality and engaging to prevent residents from simply clicking through to completion. The advent of free, open-access medical education (FOAMed) has provided physicians-in-training new avenues of learning that were not previously available prior to the widespread adoption of social media.26 Online modules, such as the Approved Instructional Resources (AIR) Series created by Academic Life in Emergency Medicine (ALiEM), which provide opportunities for residents to asynchronously earn conference credit while learning about clinical topics, have been shown to be widely adopted and valuable tools for enhancing resident education.27 We anticipate that an asynchronous curriculum teaching EM administrative topics would be equally successful.

As expected, there was a moderate correlation between topics that attendings found essential and topics that residents wanted to learn more about. It is unclear why there were such large discrepancies between resident and attending viewpoints related to the topics of informatics and entrepreneurship. As a technical, subspecialty area, it may have been possible that survey respondents did not fully understand what the field of clinical informatics entails. Additionally, while many resident respondents may be interested in learning more about entrepreneurship during residency, this interest may fade over time if they do not embark upon entrepreneurial activities early in their careers, leading to a lower proportion of attending respondents considering the topic essential. Surprisingly, there was not a strong correlation between topics that residents had below-average current knowledge and those that they were most interested in learning more about. This may be because residents are not interested in learning in certain topics that they don’t currently know about, such as informatics and quality/value-based payments, or because they want to continue to learn more about topics that they believe they have above-average knowledge of already such as documentation and well-being.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue of workforce preparedness and equipping emergency medicine graduates to be competitive applicants has been paramount. It can be hypothesized that a resident taught the practice essentials of emergency medicine may be at a competitive advantage in the job market given the value-added skills this training brings to the department and physician group. In addition, training emergency medicine resident physicians value-based payments and quality is essential as we transition to a value-based reimbursement system.

LIMITATIONS

Our national survey has inherent limitations including surveying residents about the quality of their administrative education before completing the totality of their residency training. Determination of the response rate for attendings was not possible as the survey was distributed on various department and organizational listservs, making a true denominator difficult to determine. Furthermore, it is difficult to account for potential overlap from individuals present in multiple listservs. Amongst residents invited to complete the survey, many were unwilling or unable to complete the optional survey leading to non-response bias. The sample of attending respondents is affected by voluntary response bias as likely those who are involved in resident education or those with interests in EM business and administration were more likely to complete the survey than attendings with different backgrounds. Attending responses related to their own residency training are subject to recall bias since the median time from residency graduation was 12 years.

CONCLUSION

Learning business and administrative topics is regarded as very important during residency, yet the majority of residents report low levels of knowledge and preparation and many faculty do not feel like they have content expertise. Based upon this targeted needs assessment, there is an opportunity to create a national, self-paced, online, case-based curriculum that is engaging and high value. Overall, residents and attendings agree about most, but not all, topics that should be prioritized in an EM business and administration curriculum. This is the first targeted needs assessment to identify and stratify topics of importance to both resident and attending physicians regarding the business of EM, allowing educators to confidently progress to subsequent stages of Kern’s model of curriculum development.

REFERENCES

- Frumkin K. Resident Training: The Missing Curriculum. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(1):95-96.

- ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. Published July 1, 2019. Accessed May 9, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019.pdf

- The Emergency Medicine Milestone Project: A Joint Initiative of The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and The American Board of Emergency Medicine. ACGME website. Published July 2015. Accessed on May 9, 2020. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/EmergencyMedicineMilestones.pdf

- Beeson MS, Ankel D, Bhat R, et al. The 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. [Published online ahead of print March 18 2020]. J Emerge Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.03.018

- Cantor JC, Baker LC, Hughes RG. Preparedness for Practice: Young Physician’s Views of Their Professional Education. JAMA. 1993;270(9):1035-1040. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/vol/270/pg/1035

- Frank RA. The Physician Manager: Practice Management Education in the 21st Century. Med Group Manage J. 1997;44(4):83-92.

- Heiner JD, Dunbar JL, Harrison T, et al. Current Emergency Medicine Residency Education of Documentation, Coding, and Reimbursement: Fitting the Bill? Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):S137-S138. https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(10)01052-8/fulltext

- Falvo T, McKniff S, Smolin G, et al. The Business of Emergency Medicine: A Nonclinical Curriculum Proposal for Emergency Medicine Residency Programs. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(9):900-907. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00506.x

- Welch SJ, Slovis C, Jensen K, et al. Time for a rigorous performance improvement curriculum for emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(7):783-786. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1197/j.aem.2006.03.555

- Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1998.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457.

- Kolva DE, Barzee KA, Morley CP. Practice Management Residency Curricula: a Systematic Literature Review. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):411-9.

- Werblun MN, Martin LR, Drennan MR, et al. A competency-based curriculum in business practice management. J Fam Pract. 1977;4(5):893-897.

- Adiga K, Buss M, Beasley BW. Perceived, Actual, and Desired Knowledge Regarding Medicare Billing and Reimbursement; A National Needs Assessment Survey of Internal Medicine Residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):466-470. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16704389/

- Holak EJ, Kaslow O, Pagel PS. Facilitating the transition to practice: A weekend retreat curriculum for business of medicine education of United States anesthesiology residents. J Anesth. 2010;24(5):807-810. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20563736/

- Williford LE, Ling FW, Summitt RL, Stovall TG. Practice management in obstetrics and gynecology residency curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(3):476-479.

- Patel AT, Bohmer RMJ, Barbour JR, Fried MP. National assessment of business-of-medicine training and its implications for the development of a business-of-medicine curriculum. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(1):51-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15630366/

- Williams LL. Teaching residents practice-management knowledge and skills: an in vivo experience. Acad Psych. 2009;33(2):135-138.

- Sims KL, Darcy TP. A leadership-management curriculum for pathology residents. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108(1):90-95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9208984/

- Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally training in business practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15701483/

- Jones K, Lebron RA, Mangram A, Dunn E. Practice management education during surgical residency. Am J Surg. 2008;196(6):878-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19095103/

- Berkenbosch L, Bax M, Scherpbier A, et al. How Dutch medical specialists perceive the competencies and training needs of medical residents in healthcare management. Med Teach. 2013;35(4):e1090–e1092. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23137237/

- Myers C, Pronovost PJ. Making Management Skills a Core Component of Medical Education. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):582-584. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28248694/

- AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2019 All Schools Summary Report. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published July 2019. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-08/2019-gq-all-schools-summary-report.pdf

- Salib S, Moreno A. Goodbye and Good Luck: Teaching Residents the Business of Medicine After Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):338–340. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4597941/

- Nickson CP, Cadogan MD. Free Open Access Medical education (FOAM) for the emergency physician. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(1):76-83. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1742-6723.12191

- Lin M, Joshi N, Grock A, et al. Approved Instructional Resources Series: A National Initiative to Identify Quality Emergency Medicine Blog and Podcast Content for Resident Education. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(2):219-225. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4857492/