The vague presentation of abdominal pain can lead you down many differential pathways. When combined with sudden or rapid weight loss, it can point to 2 rare syndromes caused by compression.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male presents to the emergency department with a multi-month long history of abdominal pain with vomiting that occurs primarily in the morning. He is reporting worsening of this pain over the past week in his left lower quadrant, new radiation of the pain to his left groin, with inability to tolerate solid oral intake. He has had 4 other emergency department visits at our facility over the past 3 months for similar symptoms. Multiple imaging modalities have been utilized with the most recent computed tomography (CT) occurring 6 days prior and showing only thickening of the bladder wall without acute intra-abdominal findings. On this presentation, he is afebrile with normal vital signs. Physical exam reveals moderate left lower quadrant tenderness without rebound or guarding.

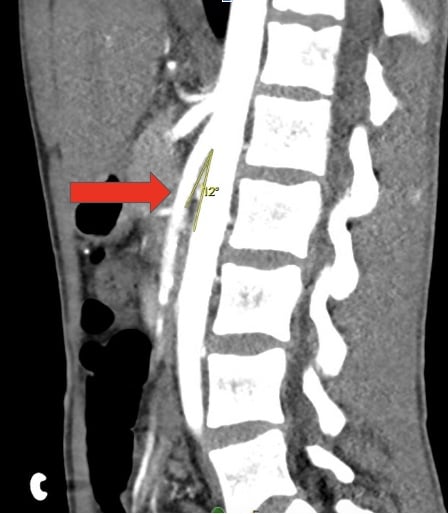

Laboratory evaluation was unremarkable; no leukocytosis, electrolyte abnormalities, or evidence of dehydration. Since the patient had already had a CT performed within the past week, we made the decision to obtain a testicular ultrasound to identify pathology which could be missed on CT. The ultrasound revealed a left hydrocele. This finding in combination with the history of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting after eating prompted evaluation with a computed tomography angiography (CTA) to exclude compressive pathology. CTA revealed an aortomesenteric distance of 5 mm, aortomesenteric angle of 12° (Image 1), and findings consistent with small bowel obstruction.

Nutcracker Syndrome

Nutcracker syndrome refers to the clinical manifestations and symptoms as a result of the compression of the left renal vein, most often between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery.1 Entrapment of the left renal vein impairs blood flow into the inferior vena cava, subsequently leading to distention and increasing pressure of the left renal collecting system, including the gonadal vein.2 Interestingly, not all nutcracker anatomy causes symptoms; such anatomical findings may be a normal variant.3 In addition to anatomical variation, rare causes of nutcracker syndrome include malignancy, pregnancy, lordosis, intestinal malrotation, and rapid weight loss.4 There are no set guidelines that dictate what manifestations and symptoms are severe enough to designate the anatomical variant as nutcracker syndrome. Nutcracker syndrome is thought to have a slightly higher prevalence in females and most symptomatic patients present during their second to third decade of life.1

The main clinical manifestations of nutcracker syndrome include hematuria, proteinuria, and pelvic pain in females, and varicocele in males. The pain is often described as flank or abdominal pain that radiates to the posterior pelvis and thigh and can be aggravated by movement.1 Nutcracker syndrome symptoms are thought to be secondary to pelvic and renal congestions and increased pressure.4 Interestingly, the pediatric population is typically asymptomatic.5 Long-term complications include hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and left renal vein thrombosis.6,7

Diagnosis is multidisciplinary and often requires multiple methods of imaging, including computed tomography imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, Doppler ultrasound, and catheter venography.2 Successful conservative treatment has been most promising in pediatric patients, likely due to increase and redistribution of adipose and fibrous tissue as they develop.2 Medications such as angiotensin inhibitors are also used in this population to increase renal blood flow and treat accompanying hypertension.4 More invasive interventions, including endovascular and extravascular stenting, are commonly pursued in adult populations.4

Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome, or Wilkie’s syndrome, is an uncommon gastrointestinal pathology in which the transverse portion of the duodenum becomes compressed between the aorta and the SMA. This pathology, described by David Wilkie in detail in a case series publication,8 most frequently leads to chronic symptoms that can include vague postprandial abdominal pain, weight loss, difficulty tolerating oral intake, and vomiting.9,10 Despite most cases causing chronic symptoms, there can be acute complications, including small bowel obstruction. Dehydration and metabolic derangements secondary to anorexia and vomiting can also occur. 9

As mentioned, the syndrome is caused by compression between the SMA and aorta; however, there are many factors that predispose a patient to this compression. Some are congenital, including an abnormal insertion point of the SMA or Ligament of Treitz leading to abnormal positioning of these structures relative to each other.9 As the duodenum is typically protected from compression by retroperitoneal fatty tissue, rapid loss of this tissue secondary to tumor burden, anorexia, or other conditions can also predispose a person to the development of SMA syndrome.11

Diagnosing Wilkie's syndrome can be difficult. An abdominal computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging test may be helpful, and certain findings are suggestive of the condition.11 The duodenum may be dilated proximal to the site of compression. A decreased aorto-mesenteric distance or decreased aorta-SMA angle may also be seen. This angle in Wilkie’s syndrome is typically between 6° to 16° in comparison to the standard angle between 38° to 65°.9 Normal aorto-mesenteric distance is between 10 to 24 millimeters. If recent, rapid weight loss is suspected as the cause of the condition, refeeding can replenish the retroperitoneal fat tissue and relieve the condition.11 However, if conservative treatment fails, surgical intervention may be necessary.9

Summary

Although they produce very different symptomatology, both nutcracker and Wilkie’s syndromes are caused by compression of structures most commonly between the superior mesenteric artery and aorta. These conditions, although rare, are important to recognize as emergency physicians, as they may present with chronic, recurring symptoms or acutely as the underlying cause of a small bowel obstruction or renal vein thrombosis. Even more rare is the combination of these pathologies, which can lead to increasingly complex sequelae in affected patients.

References

- Kurklinsky AK, Rooke TW. Nutcracker phenomenon and nutcracker syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(6):552-559.

- He Y, Wu Z, Chen S, et al. Nutcracker syndrome--how well do we know it?. Urology. 2014;83(1):12-17.

- Shin JI, Lee JS. Nutcracker phenomenon or nutcracker syndrome?. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(9):2015.

- Kolber MK, Cui Z, Chen CK, Habibollahi P, Kalva SP. Nutcracker syndrome: diagnosis and therapy. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021;11(5):1140-1149.

- Shin JI, Baek SY, Lee JS, Kim MJ. Follow-up and treatment of nutcracker syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21(3):402.

- Ananthan K, Onida S, Davies AH. Nutcracker Syndrome: An Update on Current Diagnostic Criteria and Management Guidelines. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53(6):886-894.

- Penfold D, Lotfollahzadeh S. Nutcracker Syndrome. [Updated 2022 Dec 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559189/.

- Yale SH, Tekiner H, Yale ES. Historical terminology and superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;67:282-283. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.12.043

- Claro M, Sousa D, Abreu da Silva A, Grilo J, Martins JA. Wilkie's Syndrome: An Unexpected Finding. Cureus. 2021;13(12):e20413.

- Kefeli A, Aktürk A, Aktaş B, Çalar K. Wilkie's Syndrome: A Rare Cause Of Intestinal Obstruction. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2016;29(1):68.

- Diab S, Hayek F. Combined Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome and Nutcracker Syndrome in a Young Patient: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e922619.