This case of unexplained, worsening pain and swelling in a bounceback patient was solved with bedside ultrasound and a thorough history that revealed social determinant red flags.

Case Presentation

A 38-year-old male presented to the emergency department with 2 weeks of right lower extremity swelling. He stated that he went to an outside emergency department twice the week prior, where two deep vein thrombosis (DVT) ultrasound studies were negative. He presented to our emergency department a few days later due to increased right lower extremity pain, progressively worsening leg swelling, and an inability to bear weight on the right leg due to pain. The patient stated his pain was most prominent near his groin, which had been there in the prior months.

Chart review revealed a history of HIV with intermittent adherence to antiretroviral therapy for the past year due to various stressors in his life. He was unsure of his last CD4 count but had recently re-established care at the hospital’s HIV clinic.

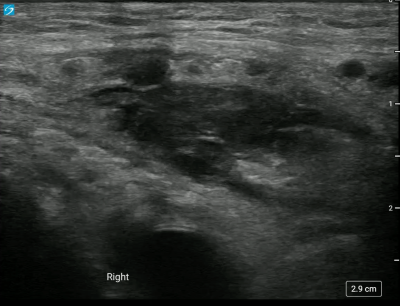

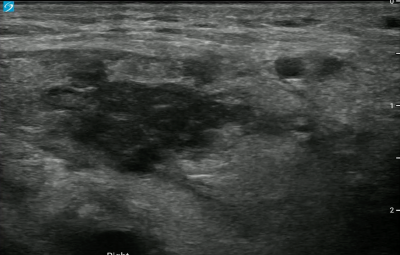

On physical examination, the patient had bulky, painful lymphadenopathy bilaterally, with significantly more lymphadenopathy on the right leg as well as lesions scattered on the lower extremities. A bedside ultrasound of the lymph nodes revealed irregularly shaped, asymmetric lymph nodes.

Image 1. Irregularly shaped, asymmetric lymph nodes seen on POCUS

Image 2. Bedside ultrasound showing lymph node irregularities

Upon asking the patient if he had ever been diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma, he revealed that he thought he had a biopsy within the past year that was positive for Kaposi. Unfortunately, our electronic medical record (EMR) did not have access to the records at the hospital where he reported having the biopsy. The patient also revealed that he had experienced housing instability and had been incarcerated over the past few years, making it difficult for him to regularly follow-up with his infectious disease physician and take his prescribed medications.

Management

Our differential diagnosis was lymphogranuloma venerum (Chlamydia trachomatis L1-L3), disseminated Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma, syphilis, and deep space abscess. The team ordered an immune deficiency panel, treponema pallidum antibody, gonorrhea/ chlamydia amplification and started the patient on doxycycline.

Due to the patient's inability to ambulate as well as his lack of stable transportation and reliable accessibility to the health care system, he was admitted to the hospital.

Discussion

Use of Ultrasound

In the radiology literature, benign lymph nodes are described as oval shaped with a thin, hypoechoic cortex (<3mm) and a hyperechoic hilum. Abnormal features of lymph nodes are: a round or asymmetric shape, calcification, ill- defined capsular margins, or a thickened cortex.1,2 These findings would make one more concerned about a malignant lymph node rather than a reactive, benign lymph node.3 While it was difficult to assess the cortex and hilum from our images, we felt confident classifying the shape of the lymph nodes as asymmetric. The use of bedside ultrasound made us more concerned about an infiltrative process, specifically Kaposi Sarcoma in this patient. Other ultrasound findings that can be found in Kaposi Sarcoma include: pleural and pericardial effusions, ascites, and hyperechoic lesions on the liver and spleen.2

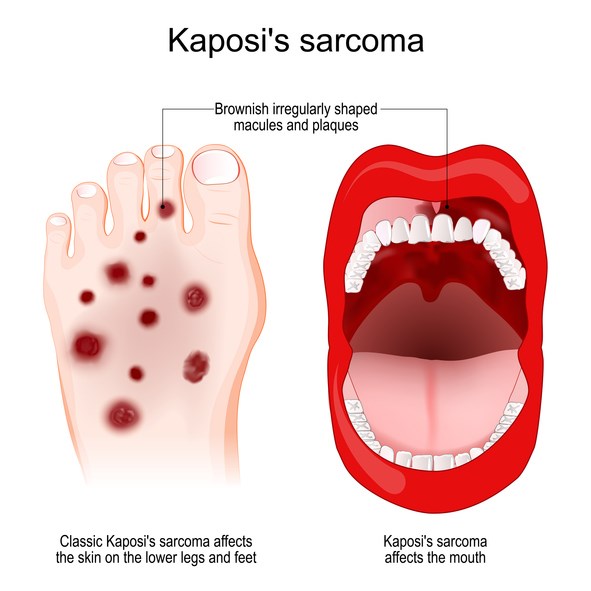

Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a malignant systemic disease that originates from the vascular endothelium and traditionally presents in 4 clinical forms. The 2 most well-known forms are in patients who are immunocompromised, such as those who have AIDS or are on immunosuppression after an organ transplant. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is present in all forms of KS and interferes with normal cell functions.

Lesions of Kaposi sarcoma are vascular lesions that appear pink or purple and can arise on the skin, and mucocutaneous surfaces such as the mouth. Additionally, there can also be involvement of the lymph nodes, lungs, spleen, and liver. Lesions and lymph nodes that are suspicious for Kaposi should be biopsied for diagnosis of the disease.

Skin lesions due to KS are treated by local excision or liquid nitrogen. In patients with systemic KS due to HIV, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) can be used with regression or full treatment of the disease seen. Severe cases of KS are treated with chemotherapy.4

Case Conclusion

During the patient's hospital admission, an MRI of the pelvis showed “Ill-defined, matted soft tissue in the right inguinal region and retroperitoneum.” A repeat skin biopsy was done, which showed Kaposi sarcoma. The patient was also found to have pulmonary nodules that were concerning for KS.

The patient was restarted on HAART as well as prophylactic medications through infectious disease consultation due to a CD4 count < 50. Prior to discharge from the hospital, the patient was scheduled for multiple paclitaxel infusion sessions to treat his disseminated Kaposi sarcoma.

References

- Goyack LE, Heimann MA. Disseminated Kaposi Sarcoma. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2021;5(4):491-493.

- Huson MAM, Kumwenda T, Gumulira J, Rambiki E, Wallrauch C, Heller T. Ultrasound findings in Kaposi sarcoma patients: overlapping sonographic features with disseminated tuberculosis. Ultrasound J. 2023;15(1):27.

- Prativadi R, Dahiya N, Kamaya A, Bhatt S. Chapter 5 Ultrasound Characteristics of Benign vs Malignant Cervical Lymph Nodes. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2017;38(5):506-515.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi Sarcoma. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Accessed May 2, 2024.