A 44-year-old male with a history of diabetes and hypertension presented to the emergency department with gradually worsening pain and swelling of his testicles over the prior few days.

The patient denied fever, dysuria, urinary incontinence, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Initial vital signs showed a temperature of 37°C, heart rate of 117, blood pressure of 126/68, and respiratory rate of 18. A physical exam revealed induration and crepitus of the perineum, scrotal edema, and mild tenderness to palpation of bilateral testicles. Laboratory testing was significant for a leukocytosis to 21 x103/uL, sodium of 128 mmol/L, glucose of 476 mg/dL, lactate of 2.9 mmol/L, and creatinine of 1.9 mg/dL. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed to evaluate for Fournier’s Gangrene (FG).

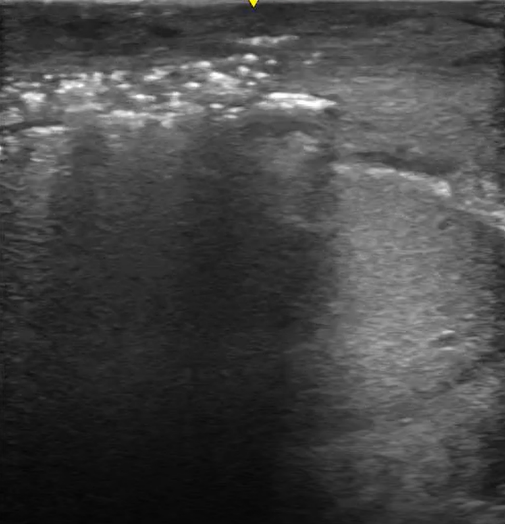

Ultrasound Findings and Technique

POCUS was performed using a high-frequency linear transducer in the affected area and demonstrated several definitive features of FG, including a thickened perineal and scrotal wall with streaks of linear hypoechoic fluid and punctate, hyperechoic foci with posterior acoustic shadowing and reverberation artifact. These echogenic foci lacked clear margins (“dirty shadowing”) and represented the pathognomonic intrascrotal gas found in FG.

The testes and epididymides are usually normal in appearance and echotexture due to separate blood supply from the scrotum. Although there is limited literature for the use of POCUS to diagnose FG, ultrasound has been shown to reliably diagnose necrotizing fasciitis in limbs with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 88.2% and 93.3%, respectively.1

Discussion

FG is a rare, life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis involving the perineal, perianal, and genital region predominantly in men with mortality rates ranging from 15% to 50%.2 The infection is commonly caused by the synergistic activity of aerobes and anaerobic organisms that produce exotoxins and enzymes leading to rapid tissue destruction, gas formation, and spread of infection. Diabetes mellitus is the major predisposing factor in addition to other risk factors of alcoholism, hypertension, and immunosuppression. Early recognition and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, surgical debridement, and hemodynamic support is crucial to management. Empiric antibiotic therapy such as piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin includes coverage for gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms as well as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Clindamycin is also a commonly included antibiotic due to its suppression of toxin production from streptococci bacteria. Delay in treatment leads to extremely poor prognosis due to the rapid progression of the disease — in some cases, the rate of fascial necrosis can spread as fast as 2-3 cm per hour.3

Although FG is most commonly diagnosed clinically, it can be challenging to identify an early presentation. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score, which stratifies likelihood of necrotizing fasciitis based on white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, glucose, creatinine, and C-reactive protein, can be used to distinguish soft tissue infections from necrotizing fasciitis. Computed tomography (CT) is the primary imaging modality and has greater sensitivity and specificity (88.5% and 93.3%) at detecting fascial gas than with plain radiography (48.9% and 94%), but is time-consuming and can delay treatment.4 In contrast, POCUS can be performed at bedside quickly and noninvasively, though sensitivity and specificity have not been well–established. Furthermore, ultrasound can detect subcutaneous gas even prior to development of physical exam findings of crepitus in the early stages of FG.5 This case highlights the value of POCUS in diagnosing this relatively early presentation of FG and ultimately expediting management of this patient’s potentially lethal infection.

Case Resolution

General surgery and urology were promptly consulted, and the patient was concurrently started on IV fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. CT of the pelvis was performed to evaluate for underlying pathology and surgical planning, and revealed extensive soft tissue gas within the scrotum tracking into the left inguinal canal consistent with Fournier’s Gangrene. The patient was taken to the operating room emergently for surgical debridement. Wound cultures grew polymicrobial organisms including Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The patient returned to the operating room five times over three weeks for extensive debridement of the scrotum, perineum, penis, testes, and skin graft placement. The patient was eventually downgraded from the surgical intensive care unit and discharged from the floor.

Image 1

Image 2

References

- Yen ZS, Wang HP, Ma HM, Chen SC, Chen WJ. Ultrasonographic screening of clinically‐suspected necrotizing fasciitis. Academic emergency medicine. 2002 Dec;9(12):1448-51.

- Eke N. Fournier's gangrene: a review of 1726 cases. Journal of British Surgery. 2000 Jun;87(6):718-28.

- Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, Rochwerg B, Kyeremanteng K, Seely AJ, Inaba K, Perry JJ. Necrotizing soft tissue infection: diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, imaging, and LRINEC score: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgery. 2019 Jan 1;269(1):58-65.

- Chennamsetty A, Khourdaji I, Burks F, Killinger KA. Contemporary diagnosis and management of Fournier’s gangrene. Therapeutic advances in urology. 2015 Aug;7(4):203-15.

- Kane CJ, Nash P, McAninch JW. Ultrasonographic appearance of necrotizing gangrene: aid in early diagnosis. Urology. 1996 Jul 1;48(1):142-4.