Ultrasound is a dynamic and innovative tool used to perform rapid evaluation and diagnosis in the emergency department. It is instrumental in the guidance of clinical decision-making, enabling real-time assessment and feedback during the resuscitation of a critically ill patient.

This case report highlights the critical role of ultrasound in the early detection of right heart strain from a pulmonary embolism and concomitant pericardial effusion with tamponade. Additionally, this case highlights how diagnostic ultrasound in real time facilitates optimal medical management in highly complex cases with a fragile hemodynamic state.

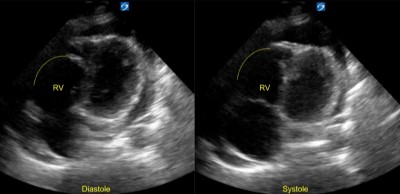

Pulmonary embolism and cardiac tamponade are already serious conditions that can precipitate acute circulatory failure in even otherwise healthy patients. A hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism can cause a substantial increase in pulmonary vascular pressure, resulting in pressure overload and dilation of the relatively thin right ventricle. Additionally, it results in an increase of physiologic dead space and a downstream reduction of left ventricular preload, which leads to the characteristic signs of tachycardia, hypotension, and hypoxia seen in our patient.

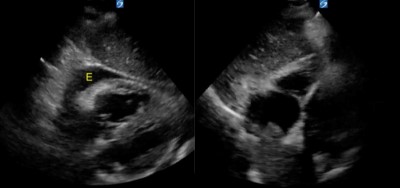

A sizable pericardial effusion of any etiology can precipitate acute cardiac tamponade once the pericardial pressures exceed that of the right ventricle, leading to the end-diastolic collapse that disrupts venous return of blood to the heart.

Simultaneous occurrence of both conditions further complicate medical management, as the elevated right ventricular pressures from the pulmonary embolism can protect it from end-diastolic collapse due to tamponade.

Although formal contrast CT imaging is the diagnostic for both conditions, it is not readily feasible to perform, especially in a patient who is too unstable for transport. Real-time sonography yielded a diagnosis within minutes of this patient’s arrival, allowing guidance of appropriate resuscitation efforts, which rendered this otherwise critical patient stable enough for definitive evaluation.

In our case report, we were able to quickly determine right heart strain with McConnell’s sign and pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology using bedside ultrasound. With diagnostic imaging, it revealed the aforementioned diagnoses along with a right atrial thrombus, bilateral pneumonia, and a right-sided pleural effusion.

Additionally, this case highlighted the procedural utility of bedside ultrasound, permitting the use of ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis compared to the traditional landmark-guided technique, which is susceptible to considerable error due to variations in patient anatomy.

Case Report

A 65-year-old Vietnamese male presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath, leg edema, productive cough, and hemoptysis. His past medical history was significant for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on diltiazem and digoxin, Stage IV lung adenocarcinoma of the left upper lobe on chemo and radiation therapy, and chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure on 2L home oxygen. He was not on any anticoagulant medications. When he arrived in the ED, the patient was afebrile, tachycardic at 106 bpm, normotensive at 114/66 mmHg, tachypneic at 20 per minute, and requiring 4L NC, tripoding in the EMS gurney.

The patient was immediately placed into a room and an initial bedside cardiac ultrasound revealed right heart strain, McConnell’s sign, and moderate pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology.

Upon verifying the patient’s code status and desire for full treatment, a Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) alert was activated. Critical care, interventional radiology, and cardiothoracic surgery services were notified as the patient underwent diagnostic labs, chest X-ray, EKG, and CT angiography of the chest.

The CT angiogram confirmed the presence of a large pulmonary embolism with RV strain, in addition to a pericardial effusion, a right-sided pleural effusion, a large thrombus in the right atrium, and bilateral pneumonia.

Scan: Effusion

The patient was given slow hydration of fluids and then placed on bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP). Meanwhile, an extensive discussion took place among ICU, IR, CT surgery, and the emergency medicine attending regarding the patient’s management. Due to his terminal cancer, he was a poor candidate for surgical intervention. The agreed-upon plan of care included an IV heparin drip for the pulmonary embolism, and thoracentesis and pericardiocentesis for the aforementioned effusions.

The thoracentesis was performed first to optimize the patient’s ventilation and oxygenation status. After 1.90L of fluid was drained from the right pleural space, the patient underwent conscious sedation with IV midazolam, etomidate, and succinylcholine.

Ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis was performed via in-line technique, using a phased-array probe in the subxiphoid view to visualize the pericardiocentesis needle in real-time as it advanced into the pericardial space. Then, 300cc of serosanguinous fluid were drained from the pericardium, yielding significant relief of the patient’s symptoms.

Scan: Pericardiocentesis

The patient was subsequently placed on a heparin drip for thrombolysis for the pulmonary embolism and was admitted to the ICU.

During the course of his hospital stay, the patient conferred with his family and made the decision to transition to hospice care. He was discharged three days later to be home with his family.

Discussion

Concomitant pericardial effusion with tamponade, pleural effusion, and pulmonary embolism are common in malignancy, which usually yields a poor prognosis. In the setting of malignant pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology and concomitant pulmonary embolism, management can be difficult. These two pathologies also seemingly work hand-in-hand due to the right ventricular pressure delaying cardiac tamponade.1

Although somewhat stable, the patient did not meet indications for pericardiotomy; however, a pericardiocentesis was indicated in order to alleviate stress around the heart and for heparin infusion. One study showed that there was no change in the overall survival of patients with a malignant pericardial effusion undergoing pericardiocentesis or pericardiotomy.2

Most emergent pericardiocenteses are performed through landmarks, but this case provided a unique learning opportunity in using ultrasound guidance and in-line technique. Procedures involving ultrasound guidance help reduce errors when compared to landmark-based techniques.3 Using in-line technique enabled us to visualize the needle and prevent any complications, such as a perforation of the ventricular wall. After 300cc of serosanguinous fluid were removed, the patient did symptomatically improve, and this enabled further medical treatment for his other complications.

Conclusion

In the setting of a malignant pericardial effusion with tamponade and pulmonary embolism, medical management can be difficult due the need for heparinization as well as pericardiocentesis. In a peri-stable patient, the use of ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis enabled us to prevent adverse outcomes and complications while providing symptomatic and therapeutic relief to the patient. It also allowed further management of the pulmonary embolism through heparinization. This case report highlights a fine balance of medical management as well as the use of ultrasound guidance in ED procedures that were previously performed blind.

References

- Akhbour S, Khennine BA, Oukerraj L, Zarzur J, Cherti M. Pericardial tamponade and coexisting pulmonary embolism as first manifestation of non-advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Pan Afr Med J. 2014 May 3;18:15. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Labbé C, Tremblay L, Lacasse Y. Pericardiocentesis versus pericardiotomy for malignant pericardial effusion: aretrospective comparison. Curr Oncol. 2015 Dec;22(6):412-6. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Nagdev A, Mantuani D. A novel in-plane technique for ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;31(9):1424.e5-9. Accessed April 26, 2022.