A trichobezoar is an intraluminal mass in the stomach or intestine composed of undigested swallowed hair.

It primarily occurs in adolescent female patients with trichophagia, trichotillomania, and other underlying psychiatric disorders. Presenting symptoms can range from abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, or an asymptomatic abdominal mass, and can progress to acute complications such as obstruction, perforation, and peritonitis. More chronic complications include weight loss and anemia due to malabsorption. Patients often present multiple times with subtle symptoms prior to being diagnosed.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is one of the most common chief complaints seen in the emergency department. Differentials are broad and can encompass nearly every organ system. However, it is important to remember one rare diagnosis: trichobezoar. Trichobezoar is the most common type of gastric bezoar and is associated with psychiatric disorders such as trichotillomania and trichophagia. Approximately 5-20% of those with trichotillomania also engage in trichophagia, which could result in trichobezoar, a large quantity of hair firmly matted together.1 A trichobezoar will typically cause abdominal pain and nausea/vomiting, but it can result in erosions, ulceration, intestinal obstruction, gastric perforation, and peritonitis.1-4

Here we present a case of an 11-year-old girl with a history of anxiety who presented to the ED with abdominal pain and was diagnosed with a gastric perforation secondary to trichobezoar.

Case

An 11-year-old girl with a past medical history of anxiety presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. Our patient was seen one week prior in the ED for generalized abdominal pain and back pain. At that time, she was noted to have abdominal distension on physical exam and was discharged home with supportive care without labs or imaging.

The patient presented this visit to the ED with constant abdominal pain associated with multiple episodes of non-bloody, non-bilious emesis. On arrival, her vital signs were heart rate 120-130 beats per minute, respiratory rate 50 breaths per minute, saturating 100% on room air, temperature 98.7°F. On physical exam, the patient was noted to be tearful, pale, and ill-appearing with abdominal distension and diffuse tenderness.

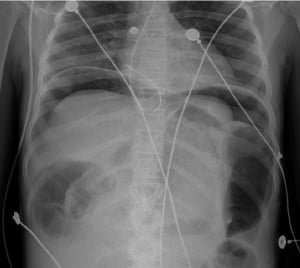

Abdominal X-ray showed a large amount of free air in the abdomen and a dilated bowel loop concerning for “bowel loop containing debris measuring up to 14 cm” (Figure 1). She was empirically started on IV piperacillin/tazobactam. On re-examination in the ED, the patient became hypoxic to 76% on room air and was ultimately intubated, with a repeat X-ray showing an increase in pneumoperitoneum (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Pneumoperitoneum on abdominal X-ray with dilated bowel loop

Figure 2: Follow-up CXR demonstrating worsening pneumoperitoneum

After intubation, the patient became hypotensive and was started on norepinephrine. Labs were significant for Hgb 7.4 g/dL, MCV 65 fL, platelets 1,341 bil/L, and WBC 7.8 bil/L. Lactic acid was 8.7 mmol/L, Cr 0.95 mg/dL, and CO2 12 mmol/L. The patient was transferred in stable condition to an outside facility for a higher level of pediatric care.

The patient was subsequently given additional intravenous fluids, started on a ketamine drip, and taken to the operating room. In the OR, gastric perforation was identified along the lesser curvature of the stomach near the angularis incisura due to a large gastric trichobezoar, with subsequent removal of the trichobezoar (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Trichobezoar in the stomach

Figure 4: After removal

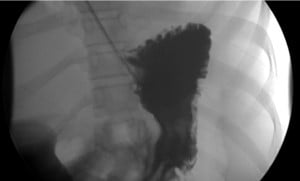

The patient was ultimately continued on antibiotics and extubated. A follow-up upper GI study showed small leakage along the lesser curvature and a postoperative ileus (Figure 5). Psychiatry evaluated the patient. She was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and trichotillomania with trichophagia, and was started on fluoxetine. She was discharged home on postoperative day nine.

Figure 5: UGI series showing small leak of contrast from the lesser curvature

Discussion

Gastric bezoars are an intraluminal mass due to the accumulation of undigested material. Although not completely understood, trichobezoars, accounting for 50% of bezoars, are thought to form as the smooth, slippery, enzyme-resistant hair stays in the gastric mucosal folds as it escapes the stomach’s peristaltic propulsion,2-5 eventually accumulating and taking shape of the stomach due to the peristalsis.3 The bezoar is then covered in mucus and gives off a putrid smell due to the fermentation of fats, potentially causing halitosis.4 Although most trichobezoars are located in the stomach due to the pyloric sphincter preventing migration, small hair can migrate as a tail through the pylorus into the intestines and colon; this is called Rapunzel syndrome.3-4

As with our patient, many are misdiagnosed on initial presentation with generalized abdominal pain, possibly delaying patient care and leading to complications. Malhotra-Gupta noted in a case review that three of 18 pediatric patients had prior diagnoses before they were finally diagnosed with trichobezoar and gastric perforation.6

With delayed diagnosis, bezoars can increase in size. This reduces blood supply to the stomach mucosa, causing ischemia specifically to the limited blood supply watershed area of the lesser gastric curvature, thus causing erosion of the gastric mucosa and eventually leading to ulceration and perforation.3,5-9

Treatment includes removal of the trichobezoar, prevention of complications, and treatment of the underlying cause. Removal includes endoscopy; however, surgery is indicated with perforation, hemorrhage, or Rapunzel syndrome.3

After treatment of the trichobezoar, a multimodal preventative therapy — specifically addressing the underlying cause — is needed to prevent recurrence. Fluoxetine and other SSRIs have been used to treat the underlying behavior of hair consumption, although no reproducible patient benefits have been seen.5

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in pediatric mental health visits both in the ED and outpatient, especially in females and adolescents.10-14 Saunders et al. found that there was a 10-15% increase in outpatient mental health utilizations, with higher ED visits and hospitalizations in females, specifically 7 to 12 years old.10 A global meta-analysis showed that specifically anxiety and depressive symptoms have doubled in prevalence since the pandemic and increased throughout the pandemic in females.13 Krass et al. even reported that 62.6% of mental health visits were female patients.14 This adds to the growing body of evidence for increasing rates of pediatric mental health prevalence.11-14

Trichobezoar prior to the pandemic had an estimated incidence of 0.4 to 1% in the general population, mainly in women younger than 30 years old,2,3,5 with most patients diagnosed having concurrent psychiatric or neurological disorders.4 However, with the rise in pediatric mental health emergencies in the past two years, it is important to consider this diagnosis and screen all patients, especially adolescents, for anxiety and depressive symptoms, with subsequent habits such as hair swallowing.

Conclusion

Trichobezoars are an uncommon diagnosis but should be considered in the differential for patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain. It is especially important not to overlook the possibility for this diagnosis in young female patients with underlying psychiatric disorders.

Take-Home Points

- Consider broad differential diagnosis for pediatric patients with abdominal pain.

- Screen all patients for depression and anxiety.

- Consider obtaining preliminary X-rays in pediatric patients with abdominal pain.

References

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL. Clinical characteristics of trichotillomania with trichophagia. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(6):579-584.

- Valenciano JS, Nonose R, Cruz RB, et al. Tricholithobezoar causing gastric perforation. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2012;6(1):26-32.

- DeBakey, Michael, and Alton Ochsner. Bezoars and concretions: A comprehensive review of the literature with an analysis of 303 collected cases and a presentation of 8 additional cases. Surgery 5.1 1939;132-160.

- Gonuguntla V, Joshi D-D. Rapunzel Syndrome: A comprehensive review of an unusual case of Trichobezoar. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2009;7(3):99-102.

- Ahmad Z, Sharma A, Ahmed M, Vatti V. Trichobezoar Causing Gastric Perforation: A Case Report. Iran J Med Sci. 2016;41(1):67-70.

- Malhotra-Gupta G, Janowski C, Sidlow R. Gastric perforation secondary to a trichobezoar: A case report and review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports. 2017;26:11-14.

- Sinha AK, Vaghela MM, Kumar B, Kumar P. Pediatric gastric trichobezoars with acute life threatening and undifferentiated elective bipolar clinical presentations. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports. 2017;16:5-7.

- Mehta MH, Patel RV. Intussusception and intestinal perforations caused by multiple trichobezoars. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1992;27(9):1234-1235.

- John O, Auer J. Trichobezoar causing recurrent gastric ulcer and perforation. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2014;127(1-2):16-16.

- Saunders NR, Kurdyak P, Stukel TA, et al. Utilization of physician-based mental health care services among children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Pediatrics. 2022;176(4).

- Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, et al. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4).

- Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020;174(9):898.

- Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19. JAMA Pediatrics. 2021;175(11):1142.

- Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, Esposito J. US Pediatric Emergency Department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(4).