Subdural empyemas are purulent fluid collections between the dura and arachnoid mater.

In infants, meningitis is the most common cause; in older children, sinusitis and otitis media are typically the primary sources that spread either through direct extension or hematogenously.1-3 Subdural empyemas are associated with significant morbidity and mortality if not recognized and treated promptly.1,4-5 Without proper treatment, the infection may spread through the subdural space resulting in increased intracranial pressures, disruption of cerebrovascular flow, and death. Associated thrombophlebitis of contiguous veins near the fluid collection may lead to cerebritis and cerebral infarction.2 As a result, morbidity includes persistent seizures and long-term neurologic deficits in up to one-half of cases.2,5 We describe here the presentation of a complicated subdural empyema in a pediatric patient.

Case

A previously healthy 10-year-old boy presented to the emergency department (ED) after his parents noticed he was limping with his right leg since that morning. The parents noted he had a tactile fever 2 weeks prior; however, his older brother had signs of an upper respiratory infection at that time. The child had been attending school daily and had been playing normally with his siblings. Associated symptoms reported included right arm numbness and one episode of vomiting that morning. The patient and parents denied any complaints of headaches, facial pain, eye pain, visual changes, ear pain, rhinorrhea, cough, rash, recent injuries, or altered mental status. Parents denied any pertinent past medical, surgical, or family history. The child was afebrile with normal vital signs on presentation. Examination revealed an alert child, answering questions appropriately for his age, and following simple commands. There was no facial swelling or tenderness. Neurologic examination was remarkable for right upper and lower extremity weakness with decreased sensation, bilateral ankle clonus, abnormal finger to nose and heel to shin test bilaterally, and difficulty with rapid alternating movements. He was unable to lift his right foot off the ground during gait testing.

On laboratory analysis, a complete blood count was significant for thrombocytosis of 559 bil/L (normal range: 140 – 340 bil/L). Inflammatory markers were markedly elevated with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 118 mm per hour (normal range: 0 – 9 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 5.7 mg/dL (normal range: 0.0 – 0.8 mg/dL). Differential diagnoses for our case included:

- Acute cerebellar ataxia, given the sudden gait disturbance and cerebellar signs

- Stroke, given the acute right-sided hemiparesis

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, given the focal neurologic deficits in the setting of fever and elevated inflammatory markers

- Clinically isolated syndrome (an isolated incident that may represent the onset of multiple sclerosis), given the potential of central nervous system (CNS) demyelination

- An intracranial lesion, given the unilateral hemiparesis

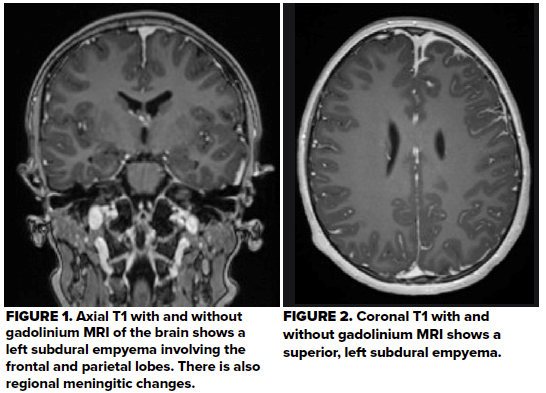

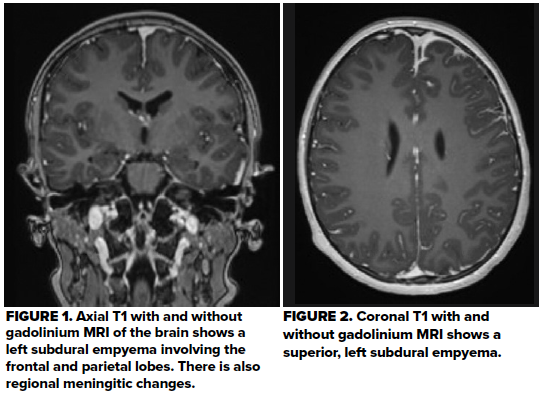

The patient's case was discussed with the pediatric neurology team, who recommended magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, cervical spine and thoracic spine with and without contrast using a multiple sclerosis protocol to evaluate for CNS lesions. This revealed a subdural empyema along the anterior hemispheric falx with left frontoparietal lobe involvement (Figures 1 and 2). These findings correlated with the predominant motor weakness of the right extremities. The MRI also showed regional meningitic changes near the anterior hemispheric collection, which may have contributed to the bilateral findings on his exam. There were also changes consistent with paranasal sinusitis. The MRI showed no abnormalities of the cervical and thoracic spine.

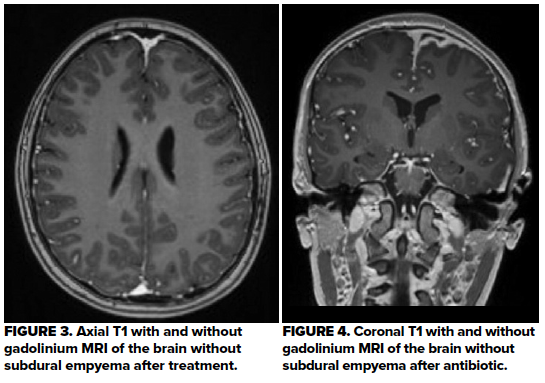

The neurosurgery team was consulted and recommended non-surgical treatment with intravenous antibiotics given that the patient’s mental status was intact without evidence of increased intracranial pressures, the small size of the purulent collection, and the risks of proceeding with neurosurgical intervention. Levetiracetam was recommended for seizure prophylaxis. In consultation with the infectious disease team, the patient was initially treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics: ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole. An MRI four days later showed improvement in the subdural empyema. His gait normalized, the paresthesias resolved, and the right-sided hemiparesis greatly improved. The patient was discharged on hospital day five with oral metronidazole, levetiracetam, and ceftriaxone via a peripherally-inserted central catheter. An MRI four weeks after discharge showed interval resolution of the subdural empyema (Figures 3 and 4). A clinic visit six weeks later noted that he was back to his neurologic baseline.

Discussion

In children, fever and headache are the most common presenting symptoms of sinusitis.2 Accepted mechanisms for sinusitis evolving to intracranial abscesses include direct extension due to close proximity of the subdural space and paranasal sinuses or hematogenous spread via the valveless diploic veins.1,2 These purulent collections can rapidly expand and cause increased intracranial pressure, potentially leading to herniation and death within 48 hours if untreated.2 Thus, prompt recognition and treatment is required to preserve appropriate neurologic function. Hemiparesis, seizures, and altered mental status are the most common neurologic signs when the intracranial space is involved.4 Other presenting symptoms, such as periorbital swelling, diplopia, or facial swelling should also prompt imaging studies, as these signs may indicate a high likelihood of empyema expanding into the intracranial space.6

The leukocyte count, CRP, and ESR may be elevated or normal in subdural empyemas.4 Blood cultures are often negative and may not be helpful in contributing to the management of intracranial abscesses.4,5 Spinal cultures are often low yield as well and not needed for diagnosis. They also pose risk of deterioration in patients with empyemas that cause mass effect and increased intracranial pressures. Neurodiagnostic imaging options include computed tomography (CT) scan and MRI. CT scans have the advantage of being readily available at most hospitals and should be done emergently if there are concerns of increased intracranial pressure. They should be performed with intravenous contrast if infectious etiologies are suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive than CT for intracranial infectious lesions; initial CT scans may miss 24-35% of intracranial abscesses.1,4 A CT scan is a reasonable first-line choice for imaging due to its accessibility, however MRI with gadolinium contrast is the preferred imaging modality if available and clinical suspicion remains high despite an initially negative CT scan.4

After establishing the diagnosis, neurosurgery, infectious disease, and otorhinolaryngology (if the cause is sinogenic) consultations are warranted for multispecialty management of subdural empyemas. Neurosurgical interventions (craniotomy or burr holes) are indicated in patients with associated sepsis, neurologic deterioration, or failure to respond to antibiotics.4,5 Stable patients may undergo conservative treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and close monitoring for signs of deterioration. A typical regimen is ceftriaxone or cefotaxime plus metronidazole, as subdural empyemas are usually polymicrobial with anaerobic gram-positive cocci and gram-negative rods.1,3 Seizure prophylaxis is recommended due to the high rate of seizures with intracranial abscesses.3 Although corticosteroids can reduce edema and inflammation, there are no documented studies in its utility for subdural empyemas and remains controversial. A conservative approach requires frequent follow-up imaging to assess for improvement and resolution of the subdural empyema. In our case, MRI studies were obtained on day one, day four, and week four.

Prior to the availability of antibiotics, CT, and MRI, subdural empyemas were almost always fatal. With advances in diagnosis and treatment, mortality rates have decreased to 6-15%.3,4 Nonetheless, survivors may have significant morbidity, including permanent residual hemiparesis (15-35%), persistent seizures (12-38%), and residual neurologic deficits in up to one-half of cases.2 Thus, it is important to consider and evaluate for intracranial abscesses in children presenting with neurologic signs and any indication of sinusitis within the past several weeks.

Take-Home Points

- Sinusitis presents variably in children and can be a potential source of intracranial abscesses, which may occur up to six weeks after initial symptoms.

- A thorough history and physical examination is essential when children present with concerning neurologic symptoms. Gait assessment can be high yield.

- MRI is the imaging modality of choice when available due to the lower sensitivity of CT scans.

- Once diagnosed, initiate a third-generation cephalosporin with metronidazole and consult neurosurgery and infectious disease early.

- Subdural empyemas have significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly diagnosed and treated.

References

- Felsenstein S, Williams B, Shingadia D, et al. Clinical and microbiologic features guiding treatment recommendations for brain abscesses in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(2):129‐135.

- Osborn MK, Steinberg JP. Subdural empyema and other suppurative complications of paranasal sinusitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(1):62‐

- Laulajainen-Hongisto A, Lempinen L, Färkkilä E, et al. Intracranial abscesses over the last four decades; changes in aetiology, diagnostics, treatment and outcome. Infect Dis (Lond). 2016;48(4):310‐

- Mameli C, Genoni T, Madia C, et al. Brain abscess in pediatric age: a review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019;35(7):1117‐1128.

- Germiller JA, Monin DL, Sparano AM. Intracranial complications of sinusitis in children and adolescents and their outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(9):969–976

- Hendaus MA. Subdural empyema in children. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(6):54‐59. Published 2013 Aug 14.