Spontaneous bilateral adrenal hemorrhage (SBAH) is a rare condition that results in adrenal crisis, shock, coma, and death. Unfortunately, symptoms are not easy to identify because they are non-specific and generalized (Dahan, et al, 263). In fact, the diagnosis often results from scans for symptoms correlated to other diseases. It is most commonly related to sepsis, physical trauma, anticoagulant therapy, coagulopathies, post-operative states, and severe stress. It can be associated with people of any age but is more common to people 40-80 years old. However, difficulty arises when there are no known specific symptoms to be associated with the underlying pathology for early diagnosis. High awareness and suspicion must be perpetuated in patients who are clinically ill under high risk factors.

The Case

A 50-year-old Hispanic female presented to the ED at 10 am complaining of severe left upper quadrant and left flank pain since 2 am the night before. The pain was associated with nausea and 4 episodes of vomiting. Pain was sharp and stabbing and did not radiate anywhere. The patient, in obvious distress and diaphoretic, confirmed she had never had a surgical operation and was not taking any medications. Vital signs upon presentation were temperature: Temperature, 97.4 F (36.3 C) oral; BP, 105/92; Pulse, 106; Respiratory, 28; MAP, 96; SpO2, 97%; Pain 1-10 scale, 10; Weight 64.3 kg.

While awaiting lab results, the patient complained of worsening pain in the same location, but this time a bit more generalized. Patient became hypoxic, stopped breathing, and suddenly became pulseless. The patient was intubated and CPR was initiated, with several rounds of epinephrine and bicarbonates. At the end of the third round of CPR, there was no pulse and there was a flat line on the monitor, with no spontaneous respirations and no heart tones.

When labs came back the only abnormality found was a platelet count of 13,000, indicating thrombocytopenia. CT scans were negative for any bleeds but did show perinephric fluid on the left side slightly greater than normal, suggesting possible inflammation.

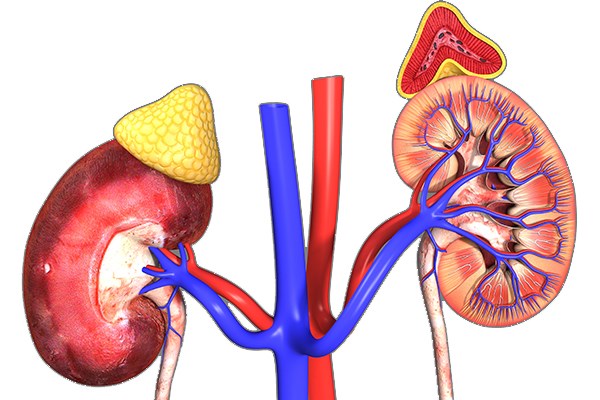

Figure 1: Left Perinephric Fluid - slightly greater than typical could suggest inflammation. Source: Loyola University Health System Radiology Department 04/2017; used with permission

Etiology

SBAH can occur because of anticoagulant therapy or an underlying coagulopathy. For example, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a known cause and results from an antibody reaction by the patient’s body against the platelets (Dahiya et al. 27). Bleeding is rare — platelet counts do not fall below 20,000 normally — but can cause adrenal hemorrhaging because of presumed adrenal vein thrombosis. HIT can cause severe arterial and/or venous thrombosis of both adrenal glands and usually presents within the first 2 weeks of commencing anticoagulant therapy. However, in this case the patient had thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of less than 20,000 and there was no use of heparin.

The adrenal gland has a rich supply of blood but has poor drainage because it depends on only one vein. Additionally, stress can exacerbate the condition. A hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) increases when an individual is stressed, causing vessels to dilate and leading to an increase in blood flow through the arteries, which in excess amounts cannot be compensated by the single draining vein. Coupling this with coagulopathies, the likelihood of SBAH is much higher.

SBAH is also attributed to a disease called Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (WFS), which leads to the failure of the adrenal glands, also known as adrenal crisis, because of excessive bleeding into the gland itself (Hammond et al. 2,476). It was commonly associated with the pathogen P. aeruginosa in children with sepsis; however, the most common pathogens responsible for this disease now are N. meningococcus and S. aureus, especially in adults. This leads to meningococcemia, which leads to the severe hemorrhaging of the glands.

SBAH can be a complication of other critical illnesses, such as shock or sepsis. Other known causes are physical trauma and postoperative states. These stressful illnesses can mask SBAH, as the non.specific symptoms associated with it cannot be distinguished from the current illness.

Signs and Symptoms

Adrenal hemorrhage has a number of generalized yet very dramatic symptoms that are seen with many different conditions — even when a single gland is affected. When both adrenal glands are affected, this disease tends to become life-threatening, especially if adrenal crisis occurs. Concern for SBAH should increase when considering the extent and duration of blood loss and the impact on adrenal gland function. The key is to provide proper therapy before symptoms of shock arise, because this can lead to coma or even death.

SBAH can be suspected through identifying symptoms like hypotension and shock greater than 90% of the time. Abdominal, back, and flank pain occurs in more than 86% of cases. Fever, nausea, and vomiting occur more than 50% of the time. In the cases including the abdomen, acute abdominal rigidity and rebound tenderness were reported in 15-20% of the cases.

Many times patients present with symptoms after more than 80% of the adrenal cortex has already suffered damage. Patients with high risk factors should raise suspicion that adrenal hemorrhage may already be occurring even though they present with non-specific yet very dramatic symptoms. Consider these cases to be emergent, with prompt examination, proper labs, and CT scans.

Management and Treatment

SBAH can be managed and treated when it’s identified in the early stages. But when the diagnosis is delayed, the condition becomes very difficult to manage and treat, which may lead to patient death. If there is suspicion of adrenal hemorrhage, then empiric treatment with glucocorticoids should be started, as patients tend to deteriorate quickly.

The most common way of finding SBAH is by doing a CT scan as a quick form of imaging. The CT scan can differentiate a hematoma from other pathologies such as tumors related to the soft tissue glands. However, an early sign of SBAH associated with bleeding cannot always be seen clearly on CT scans. MRI can be used to detect acute, sub-acute, or chronic bleeding and would be able to detect early signs of bleeding, yet would not be of much help finding other pathologies such as neoplasms. Unfortunately, it takes longer to get results with an MRI, especially when the patient is unstable. Additionally, the suspicion for SBAH would be needed for the MRI to be ordered.

Treatment may include replacement of the body fluids as well as the electrolytes, along with restoration of deficient glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, which are normally secreted by the adrenal glands (Marti et al, 80). The glucocorticoid replacements are typically hydrocortisone, prednisone, and dexamethasone, while the mineralocorticoid replacement is fludrocortisone.

In some cases — such as severe bleeding secondary to trauma — management and treatment for SBAH may be surgical. In all cases, however, prompt attention is crucial, because a patient who goes into shock has a higher rate of mortality.

Complications and Mortality

Complications of SBAH may result in a crisis like adrenal insufficiency. In cases where this occurs, sepsis or shock may follow, which can eventually lead to death. The key, as mentioned earlier, is diagnosing the illness in its early stages by maintaining a strong suspicion for this condition.

The mortality rate in patients suffering from SBAH varies depending on the severity of the predisposing illness, but it has been estimated at roughly 15%. Because many patients present with symptoms after more than 80% of the adrenal cortex is already damaged, time for diagnosis becomes crucial. Autopsy studies show that SBAH incidence used to be about 0.14%-1.8% (Xarpy VP, 214). Prior to CT and MRI scans, this diagnosis was only made during autopsy. Thanks to improved imaging modality, the rate of autopsy findings for SBAH has declined tremendously. Now the rate of autopsy finding for SBAH is usually linked to misdiagnosis of this rare complication.

Conclusion

SBAH rarely occurs, even in those with high risk factors, but when it happens, empirically starting treatment should be the first step in management. SBAH can be a fatal disease, and mortality increases when patients have prolonged symptoms. The non-specific yet increasingly exaggerated nature of the symptoms, however, make the condition hard to detect.

In this case, lab results showed thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 13,000. Patient had a negative past medical history of other illnesses and was not on any medications. CT scan showed left perinephric fluid more than the typical amount, but did not indicate an acute bleed. An MRI is better at picking up acute bleeds and could have picked up the acute hemorrhage, yet a very high suspicion would have been needed. In this case study, the patient also had the only physical symptom of severe LUQ and left flank pain, making the assumption of SBAH an even higher possibility because of the presenting high risk factor of thrombocytopenia. Once the patient became hypotensive and symptoms of shock manifested, deterioration occurred rapidly. Those with high risk factors should have the necessary imaging and labs done in order to diagnose the illness promptly — yet in this case, even with the proper labs and scans done promptly, the diagnosis wasn’t made in time to treat the patient.

References

1. Auchus RJ, Arlt W. Approach to the patient: the adult with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(7):2645-2655.

2. Dahan M, Lim C, Salloum C, Azoulay D. Spontaneous bilateral adrenal hemorrhage following cholecystectomy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2016;5(3):263-264.

3. Kovacs KA, Lam YM, Pater JL. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage: Assessment of putative risk factors by the case-control method. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80(1):45-53.

4. Marti JL, Millet J, Sosa JA, Roman SA, Carling T, Udelsman R. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage with associated masses: etiology and management in 6 cases and a review of 133 reported cases. World J Surg. 2012;36(1):75-82.

5. Picolos MK, Nooka A, Davis AB, Raval B, Orlander PR. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: an overlooked cause of hypotension. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(2):167-169.

6. Rosenberger LH, Smith PW, Sawyer RG, Hanks JB, Adams RB, Hedrick TL. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: the unrecognized cause of hemodynamic collapse associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):833-838.

7. Vella A, Nippoldt TB, Morris JC. Adrenal hemorrhage: a 25-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):161-168.

8. Xarli VP, Steele AA, Davis PJ, Buescher ES, Rios CN, Garcia-Bunuel R. Adrenal hemorrhage in the adult. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57(3):211-221.

9. Rao RH, Vagnucci AH, Amico JA. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage: early recognition and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110(3):227-235.