A 30-year-old man was transferred from an inpatient psychiatric facility to an academic tertiary care center ED for abnormal vitals and altered mental status. EMS reported that the patient was admitted to the psychiatric facility from an outside ED for psychosis in the setting of medical noncompliance.

Upon intake, the patient was found to be altered, hypotensive, tachycardic, and hypoxic, and he was subsequently transferred to our tertiary care center ED. Upon arrival to the ED, the patient was lethargic. Other than a past medical history of schizophrenia and asthma, limited history was available.

Initial vitals were BP 102/55 (68), pulse 126, respiratory rate 40, temperature 97.4 F, and oxygen saturation 97% on 4 liters nasal cannula.

The patient was in moderate distress with tachypnea; however, he had clear lung sounds bilaterally, a nontender and nondistended abdomen, no physical signs of trauma, and a grossly unremarkable neuro exam except for lethargy.

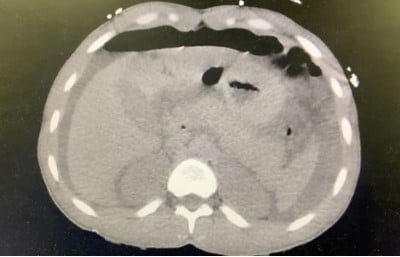

A broad workup was initiated, with strong consideration for medication-related side effects or toxicologic causes of his symptoms. Additionally, in the setting of undifferentiated hypotension, a Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension (RUSH) exam was performed and revealed free fluid in the abdomen (Image 1). Surgery was emergently consulted, and a subsequent non-contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained secondary to a creatinine of 3.51.

Image 1: RUSH exam, RUQ view

Diagnosis

CT imaging (Image 2) demonstrated free fluid and diffuse air. Discussion with family while obtaining consent for emergent surgery revealed that the patient had a history of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) with recent increasing abdominal pain, for which he self-medicated with baking soda.

Image 2: CTAP w/o contrast

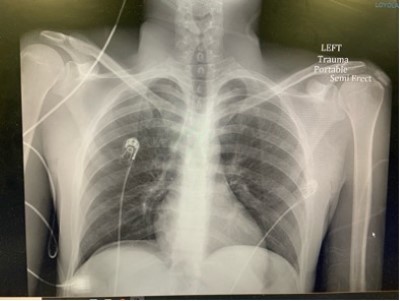

Image 3: CXR

Ultimately, the patient was found to have 1.5L of turbid ascitic fluid and a 1 cm perforated duodenal ulcer.

After operative repair, the patient was extubated on pressors postoperative day 1 and recovered without complication. He was medically cleared for transfer back to inpatient psychiatry on postoperative day 5.

Clinical Learning Points

- In the setting of undifferentiated hypotension, the RUSH exam is a quick and useful bedside tool.

- Peptic ulcer disease rarely presents as a perforation. However, it is associated with high mortality.

- Avoid anchoring on psychiatric or toxicologic diagnoses in clinically unstable psychiatric patients when limited history is available.

Discussion

This case was challenging due to the patient’s altered mental status and limited history. The RUSH exam was utilized to evaluate hypotension in this setting. Without this bedside evaluation, diagnosis and treatment likely would have been delayed.

The RUSH exam protocol was developed for rapid, systematic assessment of hypotensive patients to quickly determine if any major life threats are present. It initially focused on hemoperitoneum, pericardial tamponade, and AAA rupture. A now standardized and longer protocol, it has become an effective tool that learners can quickly grasp for bedside evaluation.

One challenge in EM is avoiding anchoring bias while assessing patients; it is even more difficult when faced with a pre-existing diagnosis of acute psychiatric illness. In 2021, an estimated 13.2 million ED visits — or about 12.3% of adults — had a listed psychiatric diagnosis. Toxicological co-ingestions are also often present in conjunction with psychiatric complaints; unfortunately, high rates of substance use disorder are linked with mental health issues.

However, this case highlights the importance of gathering more information through physical examination and considering a broad differential regardless of underlying psychiatric acute crises or chronic illnesses.

References

Dargahi H, Monajemi A, Soltani A, Nejad Nedaie HH, Labaf A. Anchoring Errors in Emergency Medicine Residents and Faculties. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2022 Oct 26;36:124. doi: 10.47176/mjiri.36.124. PMID: 36447549; PMCID: PMC9700406.

Kelly N, VandHei M, Damm T, Maricas M, Riscinti M. Rush: Undifferentiated hypotensionN. Critical Care POCUS: Assessing Your Sickest Patients. https://www.thepocusatlas.com/shock. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.thepocusatlas.com/shock

Koch E, Lovett S, Nghiem T, Riggs RA, Rech MA. Shock index in the emergency department: utility and limitations. Open Access Emerg Med. 2019 Aug 14;11:179-199. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S178358. PMID: 31616192; PMCID: PMC6698590.

Nguyen Tu. Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders. In: Mattu A and Swadron S, ed. CorePendium. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recKshRBDftMptsdq/Upper-Gastrointestinal-Disorders#h.30j0zll. Updated June 22, 2021. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recKshRBDftMptsdq/Upper-Gastrointestinal-Disorders#h.g17yk6x0693h

Rezaie, S. MD. Rush protocol: Rapid Ultrasound for shock and hypotension. RUSH protocol: Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension. https://www.aliem.com/rush-protocol-rapid-ultrasound-shock-hypotension/. Published June 1, 2013. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.aliem.com/rush-protocol-rapid-ultrasound-shock-hypotension/

Rose JS, Bair AE, Mandavia D, Kinser DJ. The UHP ultrasound protocol: a novel ultrasound approach to the empiric evaluation of the undifferentiated hypotensive patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2001 Jul;19(4):299-302. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.24481. PMID: 11447518.

Santo L, Peters ZJ, DeFrances CJ. Emergency department visits among adults with mental health disorders: United States, 2017–2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 426. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:112081external icon https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db426.htm#

Vakkil, Nimish MD. “Peptic ulcer disease: Epidemiology, etiology, and pathogenesis” Uptodate. 2022 Jul. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/peptic-ulcer-disease-epidemiology-etiology-and-pathogenesis?topicRef=26&source=see_link#H1415712