Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) remains a major cause of cardiovascular disease in developing nations. However, in industrialized nations with routine access to vaccines and antibiotics to treat Group A streptococcus, the incidence and mortality of RHD has declined dramatically since the 20th century.

Prior to the antibiotics era, the mortality rate following acute rheumatic fever was 1.5% per year, with recurrent rheumatic fever and heart failure accounting for 80% of fatalities. Severe forms of the disease can lead to fulminant heart failure in young patients, often from severe chordal and mitral valve leaflet inflammation leading to severe mitral regurgitation and even chordal rupture.

The Case

A 19-year-old male presented to the ED for shortness of breath. He complained of progressive exertional dyspnea for at least 4 days as well as cough, chills, and nausea. He had presented to a local urgent care center a day prior to evaluation in the ED, was diagnosed with “sepsis from pneumonia,” and was discharged with a prescription for oral doxycycline after 2 liters of intravenous fluid resuscitation. He presented to the ED stating he was unable to sleep flat on his back and felt worse than he did prior to his initial evaluation at the urgent care. His childhood history was remarkable for recurrent viral infections and febrile seizures. He received all routine childhood vaccines. He states that he was diagnosed with mononucleosis 10 days ago, although it was unclear where this occurred. He denied any tobacco or IV drug use.

In the ED, his initial vital signs were remarkable for tachycardia, tachypnea, and a BP of 93/45. His physical exam was remarkable for wheezing in all lung fields, bibasilar crackles, and a holosystolic murmur on his left midclavicular, 5th intercostal space. No petechiae, splinter hemorrhages, or Osler nodes were noted, and there was no lower extremity edema. A limited bedside echocardiogram was done and did not show evidence of pericardial effusion, right heart strain, or significantly reduced ejection fraction. His chest radiograph showed bilateral opacities that were worse compared to the film performed at the urgent care.

His labs were remarkable for a normal WBC, hemoglobin of 12.9, platelets of 414, normal BUN and creatinine, BNP of 230, and an initial troponin of 1.26. His EKG showed sinus tachycardia with PR depression in leads II, III, aVF, and V5-V6, but no ST elevation. His influenza swab was negative. With the troponin and BNP elevation, myocarditis versus papillary muscle rupture was suspected. He was promptly treated with furosemide 20 mg intravenously, with adequate increase in urinary output. He was also treated with intravenous antibiotics.

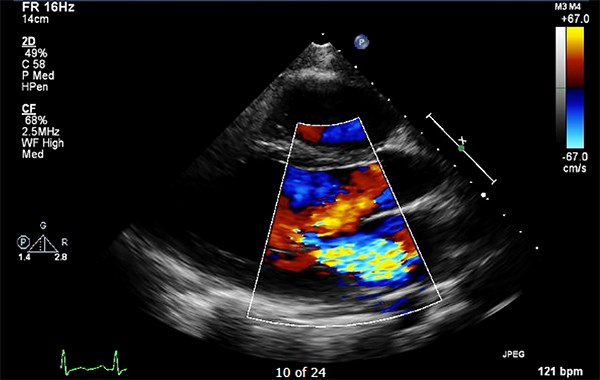

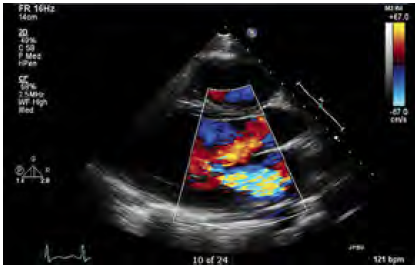

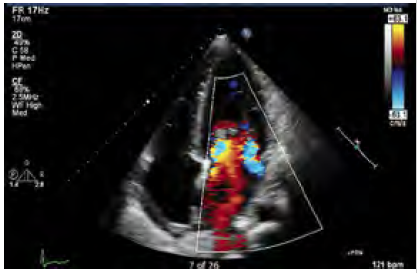

A STAT formal echocardiogram was ordered, and cardiology was consulted. The echocardiogram was remarkable for severe mitral and tricuspid regurgitation with a vegetation measuring 8 x 13 mm on his mitral valve.

The study was unable to definitively diagnose the etiology of the lesion, and cardiology admitted the patient for further evaluation and management. He was started on an esmolol drip for tachycardia. Cardiology ultimately consulted cardiothoracic surgery for mitral valve replacement. Mechanical mitral valve replacement was recommended after a transesophageal echocardiogram.

The diseased mitral valve specimen was sent to pathology and showed changes consistent with rheumatic origin. The patient tolerated surgery well, but post-operatively developed a Mobitz Type 1 AV block, which resolved prior to discharge.

Infectious disease was consulted due to the pathology findings, and the patient was started on penicillin 250 mg twice a day, which he will continue to take for 5 years. The patient was discharged home with cardiac physical therapy and close follow up with ID and cardiology.

References

1. Zuhlke L, Peters F. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease. UpToDate. Accessed May 7, 2018.

2. WHO Technical Report Series. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: Report of a WHO expert panel. Geneva 29 October - 1 November 2001. Geneva: WHO; 2004.

3. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Rheumatic Heart Disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713.