This paper underscores the essential role of comprehensive history-taking and physical examination in emergency departments to mitigate the risk of diagnostic anchoring.

Introduction

When a patient comes into the emergency department with a diagnosis listed as the cause of their ailment, clinicians can inadvertently narrow their focus influencing treatment decisions. Before seeing the patient, orders are in, and the workup is begun based on the triage note. This report discusses a case where reliance on initial triage information, which suggested a respiratory infection, could have obscured a separate life-threatening condition. By incorporating comprehensive questions and performing a diligent physical exam, the clinicians course-corrected and provided the appropriate lifesaving treatment.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old white woman was brought to the ED by EMS, with a chief complaint listed as COVID. Upon arrival, she was visibly short of breath and ill-appearing. The patient was hypotensive at 89/50 mmHg, hypoxic with an oxygen saturation of at 87% on room air, a respiratory rate of 27, a temperature of 37.6°C, and normal mentation. She reported testing positive for COVID 5 days prior and since then has had nausea, fatigue, and decreased oral intake. The patient is ambulatory at baseline, with a BMI of 37.12 kg/m2, and reports handling all her daily activities independently. However, for the past 3 days she has had worsening weakness, prompting her call to EMS. The patient has a history of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, DVT, and a remote history of thyroid, colon, and ovarian cancer in remission. The patient also states she has not been taking her medications for the past few days.

While gathering history, the patient states that her buttocks and lower back have been hurting, and she thinks the cyst on her vulva has reoccurred, which has required operative drainage previously.

On exam, the patient had an erythematous, indurated area, without fluctuance of her left hemi-vulva that was painful to palpation. Upon rolling the patient, the team found a similarly inflamed left buttock region extending 7 cm laterally from her intergluteal cleft. This appeared continuous with the inflammation on her vulva tracking through the perineum and surrounding her left perianal region. There were no areas of ulceration, palpable crepitus, or necrosis noted on exam, and no drainage from the area. The patient’s pain appeared out of proportion to her exam.

After the physical exam, our concern swiftly transitioned from a COVID-19 related ailment to concern for necrotizing soft tissue infection, particularly Fournier's gangrene, as the source of her deterioration.

Diagnostics and Initial Treatment

During the evaluation, the patient developed an increasing oxygen requirement. Although the patient remained alert and conversational during this period, she remained hypotensive despite 2L of lactated ringers. Therefore, norepinephrine vasopressor therapy was initiated, and broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered. Blood cultures, lactate, CBC, CMP, and a CT of the abdomen and pelvis were obtained.

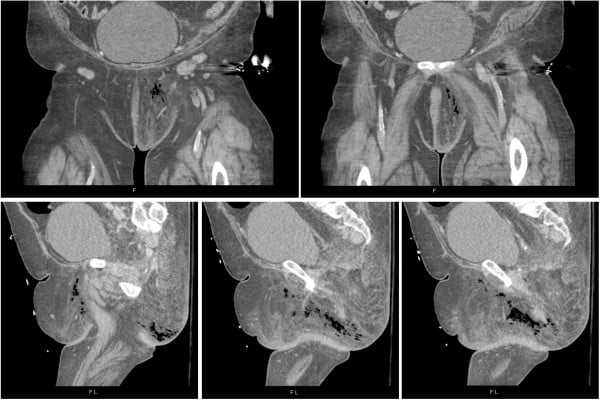

A preliminary interpretation by the emergency physician demonstrated obvious pneumoperineum with subcutaneous emphysema tracking along the left gluteal fold with left-sided pneumolabium (see Image 1).

Image 1. CT scan of our patient on presentation; frontal slices (A and B) demonstrating pneumolabium; axial slices (C, D, E) demonstrating subcutaneous emphysema tracking through the perineum

General surgery was immediately consulted for arrangement of emergent surgical debridement now that the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene was clear. The general surgeon performing surgical debridement observed the presence of “dishwasher fluid” and notable lack of bleeding during debridement, both of which are consistent with Fournier’s. Necrotic tissue encompassing the left labia majora extending to the left thigh, down to the left buttock below the anal verge was excised down to the adductor muscle. Post-procedure, the patient was transferred from the operating room to the ICU, where she continued to require high doses of vasopressor therapy - eventually necessitating a return to the OR for additional debridement for a total area of 1650cm2.

Discussion

Fournier’s gangrene is a necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) representing less than 0.02% of hospital admissions per year.1 The prevalence in females is exceedingly rare, at a rate of 0.25 cases per 100,000 female patients.1 Despite its rarity, prompt identification and surgical consultation is paramount due to a 1 in 5 mortality rate.2

Increasing the difficulty of the diagnosis, patients with necrotizing infections may present unaware of the severity of their infection due to a phenomenon known as “la belle indifference” in which the involved tissue destruction results in insensate regions of infection.3 Despite the extensive area of obvious infection on exam, this patient seemed unaware of its severity. An astute history and physical exam led to the rapid recognition of this often life-threatening condition.

References

- Sorensen MD, Krieger JN. Fournier’s gangrene: Epidemiology and outcomes in the general US population. Urol Int. 2016;97(3):249-259.

- Radcliffe RS, Khan MA. Mortality associated with Fournier’s gangrene remains unchanged over 25 years. BJU Int. 2020;125(4):610-616.

- Hussein QA, Anaya DA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(4):795-806.