Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) is a systemic disease, and the arteriolar calciphic depositon leads to vascular stenosis, thrombosis, and infarction of tissues around the body.

This can be seen anywhere in the body and is most commonly seen in distal extremities, in subcutaneous tissues with high adipose contents.1 Pain is typically exquisite. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) itself is a predictor of high mortality, which is tripled in the presence of calciphylaxis.1 Mortality of CUA in ESRD is 33%-50% at 6 months, and with penile involvement this mortality is estimated to be 50% at 3 months.1-3 Ulceration of calciphylactic lesions increases the mortality rate to above 80%,2 and superimposed infection is not uncommon.

It should be noted that not all cases of CUA are associated with ESRD; independent risk factors include warfarin therapy, primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and alcoholic liver disease.1 This is a rare pathology, and undifferentiated cutaneous lesions have a vast array of possible etiologies.4 Because clinical uncertainty is frequent, this subsect of patients represents a vulnerable population who require prompt team evaluation and subsequent medical optimization.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man with a past medical history of ESRD, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease presented with an exquisitely painful penile ulcer that had been rapidly expanding for the past 2 weeks. The patient further reported a chronic right calcaneal ulcer that was weeping fluid recently. He presented to the emergency department for 2 weeks of painful ulcer expansion. The patient has been put on calcium supplements and vitamin D for treatment of ESRD related hypocalcemia and anemia.

Vitals include a blood pressure of 148/88 mm Hg, pulse of 89 beats/minute, temperature of 98.2°F (36.8°C), respirations rate of 20 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, and body mass index of 21.02 kg/m². Physical examination noted indurated, disfiguring and exquisitely tender ulceration of the entire glans penis, with near destruction of urethral meatus (Image 1).

Image 1. Penile ulceration

Table 1. Pertinent Laboratory Values

|

|

White blood cell count 6.0 cells × 109/L (reference range 4.5 to 11.0 × 109/L)

Hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL (reference range 13.2 to 16.6 g/dL)

K 4.2 mEq/L (reference range 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L)

Blood urea nitrogen 64 mg/dL (reference range 6 to 20 mg/dL)

Creatinine 8.56 mg/dL (0.6 to 1.3 mg/dL) |

Calcium 9.1 mg/dL (reference range 8.5 to 10.2 mg/dL)

Brain Natriuretic Peptide > 4000 pg/mL (referenge range < 100 pg/mL)

C-reactive protein 3.0 mg/dL (reference range < 1.0 mg/dL)

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate 55 mm/hr (reference range 0 to 15 mm/hr)

Phosphate 9.6 mg/dL (reference range 2.8 to 4.5 mg/dL) |

|

While in the emergency department, the patient required multiple doses of morphine for control of his severe and recalcitrant penile pain. Vancomycin and cefepime were administered, given his infected calcaneal ulcer and history of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Enterobacter in previous wound cultures. The patient’s lesion was not a classic, violaceous ulcerating eschar indicating high suspicion for calciphylaxis; concern for infectious, neoplastic, vasculitic versus calciphylactic etiologies remained on the differential diagnosis.

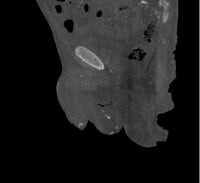

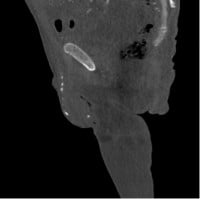

CTA with bilateral runoff was obtained, given the patient’s history of peripheral vascular disease and infected extremity ulcer. The imaging noted severe diffuse generalized arterial vascular calcification throughout all visualized arterial vascular structures including the aorta as well as the large, medium and small arteries (Images 2a and 2b). As noted, the degree/extent of arterial vascular calcifications was severe, essentially involving all arterial vascular structures diffusely.

Images 2a and 2b. Penile and testicular calcifications seen in sagittal view of computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis

Infectious disease consultation recommended cessation of antibiotics with herpes simplex swabbing, later determined to be negative. Squamous cell carcinoma was high enough to merit biopsy, which was performed by his urologist. Biopsy results indicated foci of dystrophic calcification as well as ulceration with fibroinflammatory exudate, granulation tissue, and acute inflammation of the dermis. Staining was negative for bacterial and fungal organisms.

The patient was not treated with sodium thiosulfate or hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and he declined penile amputation as a potential treatment modality. Instead, symptomatic control and goals of care discussion were prioritized. The patient’s pain improved on hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg with morphine 2 mg every 4 hours as needed while in the hospital.

He was discharged on gabapentin 300 mg daily with subjectively improved, though not resolved, symptomatic control. One month following his presentation for penile pain, he presented in volume overload from missed dialysis. While in the hospital, he unfortunately went into ventricular fibrillation and expired.

Discussion

Penile pain has primarily infectious and traumatic etiologies, which may dampen clinical concern for calciphylaxis, a diagnosis with a three-month median survival.3 Calciphylaxis affects an estimated 4% of ESRD patients and of these patients, only 6% have penile involvement.1 Resultantly, if clinicians are not considering the diagnosis, they are very likely to miss it. Clinicians should consider calciphylaxis, especially if the patient has a history of ESRD, hyperparathyroidism, warfarin use, malignancy or other risk factors.1 Calciphylactic lesions are typically acutely violaceous, subcutaneous nodules or plaques. They later evolve into necrotic, dusky ischemic necrosis. This will likely occur in conjunction with other integumentary lesions; however, it may occur as an isolated lesion like in the case presented above.

Clinicians may obtain basic chemistry, calcium and parathyroid hormone levels to evaluate for signs of renal failure, hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia in conjunction with evaluation of risk factors. Regardless, diagnosis is largely clinical. The differential diagnosis may include neoplastic, infectious, vasculitic, iatrogenic, atherosclerotic or autoimmune etiologies. It may resemble squamous cell carcinoma, sexually transmitted infection, cellulitis, warfarin skin necrosis, cholesterol embolism, or vasculitis. Gabel et al. noted in a study that of 119 patients diagnosed with calciphylaxis, 73.1% were initially misdiagnosed with the vast majority receiving antibiotics for presumed cellulitis.4 A multidisciplinary team is therefore recommended for proper diagnosis and treatment.

To definitively diagnose calciphylaxis, a biopsy visualizing calcific arteriolopathy is required; however, it is not encouraged. Conservative management is typically recommended, because trauma to calciphylactic lesion risks worsening of the patient’s pain, extension of the lesion, infection, and ulceration. Infection of these lesions is the primary cause of high mortality and ulceration carries greater than 80% mortality rate. 1,2,5,6 Varying treatment success has been noted in multiple case reports, including sodium thiosulfate, hyperbaric oxygen and penectomy.7-10 Floege et al. reported a significant reduction in the development of calciphylaxis with initiating cinacalcet when patients begin dialysis; however, this study has been criticized for a poor attrition rate and further studies are required to determine measurable benefit.11 Large-scale evaluation of each of the above treatments has found mortality benefit.1

The patient presented in this paper is an unfortunate example of the swift mortality following penile calciphylaxis. Without any treatment modalities demonstrating mortality benefit, goals of care discussion is perhaps the most productive intervention available. Symptomatic control should be attained through acetaminophen and opiate medications.12 Morphine and codeine are at risk of accumulation in reduced kidney function, so hydromorphone, fentanyl, or methadone are preferred.

Conclusion

Penile calciphylaxis is a harbinger of looming mortality, indicating need for a clear goals of care discussion. Biopsy is not routinely recommended, as this can increase risk for ulceration and superinfection and worsen outcomes. No treatments have established mortality benefit, though cinacalcet, sodium thiosulfate, and penectomy have shown benefit in case reports. Pain control is the mainstay of therapy, with acetaminophen, hydromorphone, and fentanyl as the primary recommended medications. This pathology is best cared for by a multidisciplinary team.

Attestation

The Henry Ford Institutional Review Board does not require approval for case reports with the exception of genitalia. The photographs obtained in this photo were obtained with informed consent and knowledge they may be used for publication and educational purposes. This consent is submitted with the associated manuscript.

References

- Nigwekar SU, Thadhani RI. Calciphylaxis (calcific uremic arteriolopathy). In: Post TW, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, Inc.; 2023.

- Fine A and Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61(6):2210-7.

- Gabel C, Chakrala T, Shah R, et al. Penile calciphylaxis: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(5):1209-17.

- Gabel CK, Blum AE, François J, et al. Clinical mimickers of calciphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(6):1520-7.

- El-Taji O, Bondad J, Faruqui S, et al. Penile calciphylaxis: a conservative approach. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2020;102(2):e36-8.

- Bath K and Al Jaber E. Penile calciphylaxis. Clin Case Rep. 2020;9(1):580-1.

- Hamedoun L and Mohamed T. Penile calciphylaxis: rare and unrecognized disease. Pan Afr Med J. 2022;41:124.

- Lipinski M and Sahu N. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy improving penile calciphylaxis. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9190.

- Adler K, Flores V, Kabarriti A. Penile calciphylaxis: a severe case managed with partial penectomy. Urol Case Rep. 2021;34:101456.

- D'Assumpcao C, Sharma R, Bugas A, et al. A fatal case of penile calciphylaxis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2022;10:23247096221076275.

- Floege J, Kubo Y, Floege A, et al. The effect of cinacalcet on calcific uremic arteriolopathy events in patients receiving hemodialysis: the EVOLVE Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(5):800-7.

- Davidson SN. Management of chronic pain in advanced chronic kidney disease. In: Post TW, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, Inc.; 2023.