Disposition is Critical in Determining Urgency

Overview

A 7-month-old infant with a history of recurrent ear infections and a family history of von Willebrand disease presented to the emergency department with dark tarry stools. The family reported that symptoms started approximately 24 hours prior to arrival, prompting them to go to a local emergency department. At that time, the patient had a normal exam and normal abdominal X-ray, but a positive fecal occult blood test. The patient, a female, was discharged home with a pantoprazole prescription and urgent outpatient pediatric gastroenterology referral.

At her primary care follow-up the next morning, the patient appeared pale. Point-of-care hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL. Due to ongoing symptoms and significant anemia, the patient was sent to the pediatric tertiary care hospital for further evaluation.

In the emergency department, the family reported a total of three episodes of melanotic stools, decreased appetite, and increased sleepiness. The parents denied abdominal discomfort, constipation, vomiting, hematemesis, easy bruising or bleeding, sick contacts, or fevers. She did have an ear infection treated with penicillin 2 months prior but no other recent illness. Parents denied recent travel, ill contacts, or exposures to farm animals or reptiles.

Findings and Work-Up

Vital signs: Temp=36.4oC, HR=173, RR=34, BP=122/68, SpO2=100%

Physical exam: The patient was pale but nontoxic-appearing and was smiling and interactive, in no acute distress. The oral mucosa was moist. Cardiac exam was significant for tachycardia but without cardiac murmurs or gallops. She had normal peripheral perfusion. She had no increased work of breathing with clear and equal lung sounds. Her abdomen was soft, non-tender, non-distended with normal bowel sounds. There were no masses or hepatosplenomegaly. A large amount of dark black tarry stool was in the diaper with blood-tinged/maroon-colored stool around the buttocks and perianal region. There was no skin breakdown, anal fissure, or hemorrhoids. The patient’s skin was pale. No rashes, bruising, or petechiae were present.

Initial Work-Up: Shortly after the patient arrived, an IV was placed. A weight-based dose of pantoprazole was given due to concern for GI bleed of unknown etiology. Repeat complete blood count in the emergency department demonstrated a hemoglobin of 7.8 gm/dL and a white blood cell count of 15k. Platelet count, PT/INR, and renal function were within normal limits. A type and screen was sent to the blood bank. Rapid stool studies were negative for pathogens, and a stool culture was sent. Emergent transabdominal ultrasound was performed with no abnormalities found. Pediatric general surgery and gastroenterology were consulted.

Management

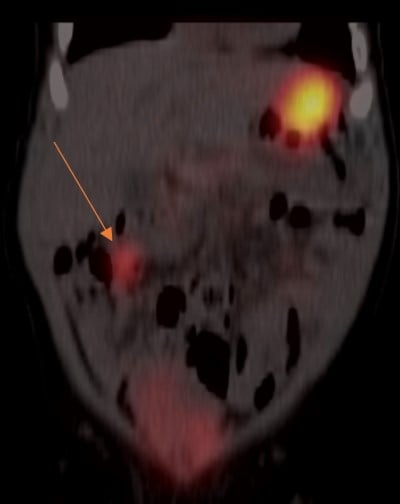

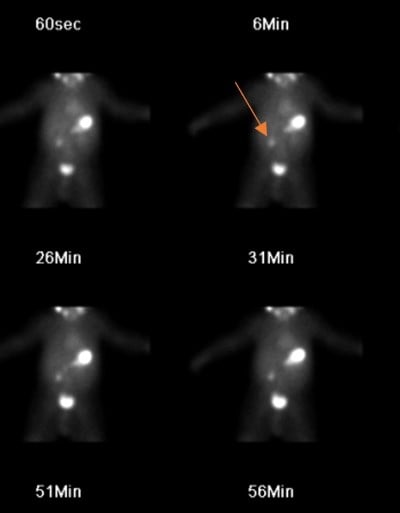

The patient’s family was updated with the labs, radiologic findings, and the medical teams’ concern for GI bleed possibly due to a Meckel’s diverticulum. The case was discussed with the on-call surgeon and gastroenterology specialist. The patient was admitted for a nuclear medicine Meckel's scan and serial abdominal exams as well as monitoring for hemodynamic instability. The findings of the Meckel’s scan were consistent with ectopic gastric mucosa in the right central abdomen, consistent with a Meckel's diverticulum. Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed and confirmed a Meckel’s diverticulum with surrounding inflammation. The area was resected (diverticulectomy).

Figure 1: Meckel’s scan showing right-sided ectopic gastric mucosa signal

Figure 2: Meckel’s scan showing right-sided ectopic gastric mucosa signal

The patient tolerated the procedure well without complication. Post-operatively, she tolerated a normal diet, had no significant pain, and no additional melanotic stools. She was discharged the next day in good condition. No other follow-up information was available.

Discussion

Pediatric GI bleeding is a somewhat uncommon presentation to the emergency department. Upper GI (UGI) bleeding accounts for approximately 1 to 2 per 10,000 visits per year, and lower GI (LGI) bleeding is slightly more common at 30 per 10,000 visits per year in the ED. There are many causes of UGI and LGI bleeding in children, and the causes vary by age group. The emergency provider’s differential diagnosis should be guided by the child’s age and appearance (sick vs. not sick).

Common causes of GI bleeding that can present at any age include fissures, infectious gastroenteritis/colitis, polyps, and vascular malformations.

In the neonate (0-30 days), GI bleed should be considered serious until proven otherwise! In a sick-appearing neonate, worrisome and life-threatening diagnoses include necrotizing enterocolitis, malrotation with volvulus, andcoagulopathy (Vit K deficiency, inherited). In the well-appearing neonate, the differential includes anal fissures, swallowed maternal blood, and allergic proctocolitis.

In the well-appearing infant/young child (1-5 years), consider fissures, infectious colitis, gastritis, benign polyps, swallowed blood from epistaxis/food or food coloring/medications (cefdinir). In the unwell infant (tachycardic, pale, dehydrated, etc.), the provider must consider intussusception, cryptic liver disease, esophageal bleeding/hemorrhagic gastritis, vascular malformation, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and Meckel’s diverticulum.

Patients with intussusception or Meckel’s diverticulum may initially appear well but then decompensate due to rapid blood loss or gut ischemia.

Finally, in the well-appearing older child/adolescent (5-18 years), consider esophageal irritation/gastritis and peptic ulcers. Ill-appearing patients include those with liver disease (varices), severe gastritis, vascular malformation, or inflammatory bowel disease.

This case portrays a young child with GI bleeding who ultimately was diagnosed with a Meckel’s diverticulum. Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital malformation of the GI tract and one of the most common causes of GI bleeding in the toddler. It is caused by ulceration of the small bowel due to acid secretion by ectopic gastric mucosa within the diverticulum.

These patients (as with the patient in this case) often present with painless LGI bleeding. If the diverticulum is inflamed, it can cause abdominal pain and tenderness. The diagnostic study of choice is a technetium-99m scan (Meckel’s scan), but definitive diagnosis is via laparoscopy with tissue biopsy.

The features of a Meckel’s diverticulum are easily (or not so easily) remembered by the “Rule of Twos”: presents by age 2, affects 2% of the population, 2 inches in length, 2 types of mucosae, within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve.

Disposition is critical for the pediatric patient with a suspected GI bleed. For the well-appearing child with normal vital signs, minimal/mild bleeding, and a reassuring exam, diagnostic work-up including stool studies and routine labs can be obtained in the ED, and an urgent pediatric gastroenterology clinic follow-up is often sufficient.

In the unwell-appearing child regardless of age: Resuscitate! Proton pump inhibitors may be beneficial in some conditions such as hemorrhagic gastritis or Meckel’s diverticulum. Consider blood transfusion (start with 10ml/kg of packed red blood cells) if the child is unstable or has severe symptoms from anemia. Labs to order include complete blood count, coagulation studies, type and screen, and stool testing/cultures. Imaging may be helpful in some cases (abdominal X-ray or ultrasound, CT scan), but do not delay in consulting your pediatric surgeon, gastroenterologist, and intensivist. These cases often require urgent endoscopy or laparoscopic surgery and pediatric intensive care unit admission.

Conclusion

For the pediatric patient with a GI bleed: Think worst first! Serious causes can be difficult to distinguish at first, so stay vigilant. Bloody stools with abnormal vitals or exam findings are concerning! Remember the age-based differential and consult your specialist team early if your patient has concerning features or findings.

References

Osman D, Djibré M, Da Silva D, Goulenok C; group of experts. Management by the intensivist of gastrointestinal bleeding in adults and children. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2(1):46. Published 2012 Nov 9.

Sagar J, Kumar V, Shah DK. Meckel's diverticulum: a systematic review [published correction appears in J R Soc Med. 2007 Feb;100(2):69]. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(10):501-505.

Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. New York: McGraw Hill Professional; 2020.

Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 9e. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2018.