Acute, persistent headache in a pediatric patient with no recent trauma can have a broad differential and, in most cases, should raise red flags. This case demonstrates the evaluation and management of cerebral abscess in a child.

Case

A 12-year-old male presented to the pediatric emergency department for intractable and worsening left frontoparietal headache during the past 6 days, unresponsive to ibuprofen. The patient also reported neck stiffness, vomiting, and photophobia. Of note, he had extensive medical history, including surgical pulmonary valve repair shortly after birth.

The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. Neurologic exam and visual acuity were unremarkable. There was neck stiffness and a positive Jolt test, but Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s were negative. A comprehensive laboratory workup yielded normal values. His headache was partially relieved with ketorolac and metoclopramide; however, given his medical history and duration of symptoms, a CT brain was ordered.

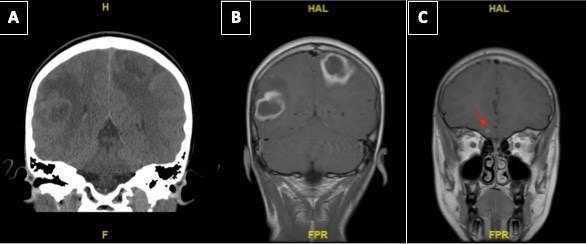

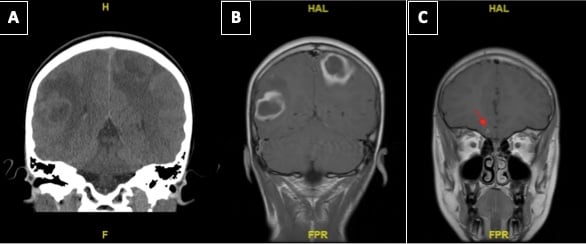

The non-contrast brain CT revealed bilateral ambiguous defects (Figure 1A), necessitating MRI and pediatric neurosurgical consultation. The MRI brain with contrast demonstrated bilateral ring enhancing lesions and a third tiny focus. See Figure 1 (B and C). These lesions were consistent with abscess formation, but malignancy could not definitively be ruled out.

Figure 1. A. CT imaging with right and left hemisphere hypodense lesions with surrounding vasogenic edema. B. T1 weighted MRI brain with contrast demonstrating peripheral with thick rim of enhancement of the lesions with low T1 signal and vasogenic edema. There is also questionable leptomeningeal enhancement. C. T1 weighted MRI brain with contrast demonstrating a gyrus rectus lesion.

Cerebral Abscess Overview

Signs and Symptoms

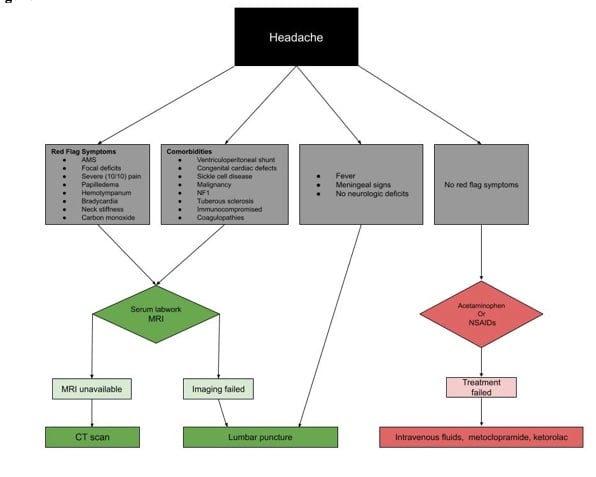

The classic triad of a cerebral abscess is unilateral headache, fever, and focal neurologic deficits.1 Similar to the above patient, cerebral abscesses may present without the complete triad. Other clinical symptoms typically include papilledema, vomiting, and neck stiffness, as well as focal neurologic changes, fever, and seizures.1 All of these findings are headache red flags and should receive an expanded workup to include imaging.2 A brief pediatric headache algorithm is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pathology

Cerebral abscesses begin with an initial focal cerebritis without pus or capsule formation (similar to our patient’s third focus in Figure 1C)3. These focal lesions worsen over 10-14 days to form an encapsulated suppurative lesion, now referred to as a cerebral abscess.3

The most common organisms include S. pneumoniae and viridans, followed by S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and group B streptococcus (GBS).4 However, one should consider predisposing factors for the most likely respective causative organism (Table 1).1 Others not included in the table are neurocysticercosis from Taenia solium and other parasites such as Paragonimus, Schistosoma japonicum, and Entamoeba histolytica.1, 5-7 These organisms typically aren't considered unless the patient has been to the respective endemic areas.

Table 1. Predisposing factors, causative agents, and management of cerebral abscess, respectively. RIPE = Rifampin, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol. TMP-SMX = Trimethoprim Sulfamethoxazole

|

PREDISPOSING FACTORS (Column A) |

CAUSATIVE (Column B) |

EMPIRIC ANTIBIOTICS (Column C) |

| Neonate |

Proteus |

Cefotaxime & Ampicillin |

| Immunocompromised | Fungi M. tuberculosis Nocardia |

Ceftazidime, Vancomycin & Metronidazole +/- Amphotericin (fungal), RIPE (tb) TMP-SMX (Nocardia) therapy |

| Congenital heart disease | S. viridans Microaerophilic streptococci Haemophilus |

Ceftriaxone & Metronidazole +/- Vancomycin |

| Middle ear infection | Streptococci Enterobacteriaceae Pseudomonas |

Ceftriaxone & Metronidazole |

| Sinus infection | Streptococci S. aureus Enterobacteriaceae |

Ceftriaxone & Metronidazole +/- Vancomycin |

| Oral cavity infection | Mixed anaerobic flora Streptococci S. aureus Enterobacteriaceae |

Penicillin + Metronidazole or ampicillin-sulbactam |

| Post-traumatic | S. aureus Streptococci Enterobacteriaceae |

Ceftriaxone & vancomycin |

Risk Factors

Direct inoculation is high risk for an intraparenchymal abscess and can include penetrating trauma or nearby infection. See Table 1, column A1. Another risk factor is hematogenous spread, which will likely present with multiple foci.1 The likely organism is based on the age and health status of the patient, in addition to the source of infection, succinctly summarized in Table 1.

Diagnosis

CT scans have a relatively low sensitivity for cerebral abscess and may not pick up early cerebritis.8 Nonetheless, CT is still generally the reasonable, initial imaging modality in the ED due to ease of access. MRI is the diagnostic modality of choice, however, based on its impressive diagnostic value: "The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy of echo-planar diffusion-weighted MRI in the diagnosis of intracerebral abscesses was 85.64%, 95.88%, 93.82%, 90.14%, and 91.56%, respectively."9

A lumbar puncture (LP) is not recommended with space occupying lesions due to a theoretical risk of tonsillar herniation and adds little diagnostic value.10-12 Despite the classical teaching, not all ring-enhancing lesions are abscesses. The differential diagnoses for ring-enhancing lesions is broad and memorable with the MAGICAL DR mnemonic (Table 2).13

Table 2. Differential diagnosis for ring enhancing lesions

| M | Metastasis |

| A | Abscess |

| G | Glioblastoma |

| I | Infarct or inflammatory (tuberculoma, neurocysticercosis, aspergillosis) |

| C | Contusion |

| A | AIDS (toxoplasmosis or cryptococcus) |

| L | Lymphoma (immunocompromised patient) |

| D | Demyelination |

| R | Radiation necrosis |

Pharmacological Treatment

Consider supportive pain medications like acetaminophen or NSAIDs while pending workup results. In patients unresponsive to these medications, add a combination of intravenous fluids (20 mL/kg, ketorolac (0.5 mg/kg, max 15 mg), metoclopramide (0.2 mg/kg, max 10 mg), and, if needed, magnesium or steroids.14-16 Appropriate antibiotic regimens are described in Table 1, column C. The lesions will often require neurosurgical intervention.

Case Conclusion

Given the broad differential diagnosis of ring enhancing lesions and the lack of classic findings for cerebral abscess, including neuro deficits on physical exam, antibiotics were held until after the lesions were confirmed, intraoperatively, to be abscesses.

The patient received levetiracetam while awaiting neurosurgery. The abscesses were eventually drained, and he made a full recovery without neurologic compromise. The patient was referred to cardiology on discharge to investigate the pulmonary valve repair, as this was theorized to be the source of the septic emboli, but the patient was lost to follow-up.

References

- Sheehan JP, Jane JA, Ray DK, Goodkin HP. Brain abscess in children. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24(6):E6.

- Lewis DW, Ashwal S, Dahl G, et al. Practice parameter: evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headaches: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2002;59(4):490-498.

- Britt RH, Enzmann DR, Yeager AS. Neuropathological and computerized tomographic findings in experimental brain abscess. J Neurosurg. 1981;55(4):590-603.

- Brouwer MC, Coutinho JM, van de Beek D. Clinical characteristics and outcome of brain abscess: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82(9):806-13.

- Correa D, Sarti E, Tapia-Romero R, et al. Antigens and antibodies in sera from human cases of epilepsy or taeniasis from an area of Mexico where Taenia solium cysticercosis is endemic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93(1):69-74.

- Ohnishi K, Murata M, Kojima H, Takemura N, Tsuchida T, Tachibana H. Brain abscess due to infection with Entamoeba histolytica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51(2):180-2.

- Patel K, Clifford DB. Bacterial brain abscess. Neurohospitalist. 2014;4(4):196-204.

- Gaillard F, Gilcrease-Garcia B, Smith H, et al. Cerebritis. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org. May 2, 2023.

- Siddiqui H, Vakil S, Hassan M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Echo-planar Diffusion-weighted Imaging in the Diagnosis of Intra-cerebral Abscess by Taking Histopathological Findings as the Gold Standard. Cureus. May 16;11(5):e4677.

- Heilpern KL, Lorber B. Focal intracranial infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. Dec 1996;10(4):879-98.

- Gower DJ, Baker AL, Bell WO, Ball MR. Contraindications to lumbar puncture as defined by computed cranial tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(8):1071-4.

- Seshia SS, Abu-Arafeh I, Hershey AD. Tension-type headache in children: the Cinderella of headache disorders! Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(6):687-95.

- Refaey M. Cerebral ring enhancing lesions (mnemonic). Reference article, Radiopaedia.org. May 2, 2023. Accessed May 2, 2023.

- Kaar CR, Gerard JM, Nakanishi AK. The Use of a Pediatric Migraine Practice Guideline in an Emergency Department Setting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(7):435-9.

- Szperka C. Understanding Pediatric Migraine. American Migraine Foundation. May, 1, 2023.

- Johnson R, Griffin, J, McArthur, J. Current Therapy in Neurologic Disease. Mosby, Inc. ; 2006.