Meningitis, inflammation of the tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord, can be a result of viral, bacterial, or fungal infection. Viral causes are more common, with enterovirus leading the pack on causes of meningitis.1

The incidence for viral meningitis in the United States is fairly low, which may be due to reporting patterns, but has been noted to be higher in certain countries.1,2

While viral meningitis usually has a less complicated course compared to bacterial, there are certain viruses — such as herpes (HSV) and associated viruses such as varicella-zoster (VZV) — that may lead to increased neurological complications. While VZV is common in populations around the world from childhood to adulthood, it is mainly limited to cutaneous manifestation (varicella causing chickenpox in younger populations and reactivation of the virus causing zoster in adults).3,4 Reactivation of VZV usually occurs in adulthood and is due to reactivation in the dorsal root ganglia after primary infection.5 This commonly causes a painful vesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution called herpes zoster and can subsequently cause post herpetic neuralgia. Reactivation of VZV also has been linked with neurological complications such as vasculopathy, myelopathy, neuropathy, and meningitis/encephalitis.6 Although believed to be rare, VZV is actually noted to be the third most frequent cause of viral/aseptic meningitis in the world.4

We present a case of an immunocompetent, elderly patient who developed VZV meningitis/encephalitis and subsequent status epilepticus after being diagnosed several days prior with cutaneous zoster infection.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 73-year-old female who was recently seen in the ED and diagnosed with varicella zoster infection. At that time, she was started on valacyclovir and discharged back home. She then presented back to the ED two days later with concern for altered mental status as well as generalized weakness. A physical exam showed a vesicular rash over the left posterior shoulder, noted by nursing staff. The patient’s vital signs were normal, and there was no focal weakness or numbness. There was a vesicular/shingles-type rash over her left shoulder in a dermatomal pattern.

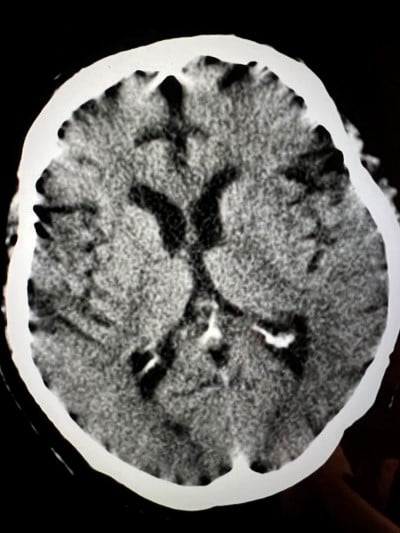

The patient presented to a community ED with concern for stroke versus seizure-like activity. She was subsequently transferred for a higher level of care. Upon arrival at the tertiary center, the patient developed a seizure. She was treated with 4mg Ativan, given Keppra as well as phenytoin without resolution, and subsequently was intubated for airway protection and started on propofol. A CT and CTA of her head did not show any large vessel occlusion or other acute process. Given the skin exam findings initially noted by nursing staff, a lumbar puncture was performed on hospital day zero, and a meningitis panel was positive for VZV as well as high protein load.

Discussion

Meningitis is a cause for concern when it comes to a patient in the ED. It is one of those cannot-miss diagnoses, as there are devastating neurological complications that can occur if bacterial, fungal, or certain viral infections go untreated.

Incidence rates vary based on country and age group, depending on reporting requirements. Viral meningitis has been reported as the most common culprit, with VZV being third behind enterovirus and HSV-2 as far as viruses go.4

The most common symptoms that may lead you down the path toward diagnosing meningitis include fever, headache, photophobia, and neck stiffness.2,7 Other symptoms include confusion, delirium, and nausea/vomiting, along with signs of increased intracranial pressure such as seizures or focal neurological deficits, which tend to carry a worse prognosis.7

In specific cases, such as the VZV meningitis/encephalitis mentioned, there may be cutaneous manifestations that may help clue you into the diagnosis (although these are not always present).8 Even for VZV meningitis, the most common symptoms were the ones previously mentioned, including fever, headache, and neck stiffness.4

Once you are heading down the path of meningitis, the next step of diagnosis is performing a lumbar puncture. Certain cases — such as immunocompromised state, recent seizures, history of central nervous system (CNS) disorders, focal neurological findings, or other findings of increased intracranial pressure — would warrant CT imaging prior to performing a lumbar puncture, but in most cases this is not necessary.2 CSF should be sent off for evaluation of cell count, protein, glucose, culture, gram stain, and meningitis/encephalitis PCR panels. As is the case for most aseptic meningitis, VZV included, pleocytosis is commonly noted but not always present. Elevated CSF to serum albumin ratio is present in VZV vasculopathies, myelitis, facial palsy, and encephalitis.9 Encephalitis panel is usually also positive, but time to results can vary. Other lab work is nonspecific in the diagnosis of VZV meningitis/encephalitis, including inflammatory markers or neuroimaging.4,9

Treatment should be started without delay on patients with concern for meningitis. In cases of possible bacterial meningitis, treatment includes ceftriaxone and vancomycin; depending on the patient’s age, the addition of ampicillin may also be considered. In certain populations such as immunocompromised patients, the addition of antivirals and antifungals may also be necessary.

While most viral meningitis has an uncomplicated course and mainstay of treatment is supportive care with antipyretics and hydration, certain infections such as HSV and VZV require treatment.1,2 Based on Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines, treatment is usually 10-14 days of IV acyclovir, with severe cases requiring up to 21 days of treatment. Certain reports have shown that oral valacyclovir can have similar efficacy without complications that can occur with prolonged hospitalization.10

Even with appropriate treatment, there is a reported 9-20% mortality rate in cases of encephalitis. In most patients who survive, neurological sequelae ranging from mild to severe are still reported. There are fewer outcome results for cases of VZV meningitis, although it appears to be more common in younger populations with less mortality or major neurological deficits.9

The pathophysiology of viral spread to the meningeal space has been debated and is still not fully understood. It has been proposed that it may spread to nerve roots close to the CNS, facilitating transfer to the meningeal space. It also has been theorized that there is hematogenous spread to the CNS.5

Conclusion

The patient remained intubated for nearly 10 days. Her status epilepticus resolved, and she was treated with acyclovir. The patient subsequently was extubated with a guarded prognosis.

References

- Kohil A, Jemmieh S, Smatti MK, Yassine HM. Viral meningitis: an overview. Arch Virol. 2021;166(2):335-345. doi:10.1007/s00705-020-04891-1

- Putz K, Hayani K, Zar FA. Meningitis. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2013;40(3):707-726. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.06.001

- Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Gilden DH. The expanding spectrum of herpesvirus infections of the nervous system. Brain Pathol. 2001;11(4):440-451. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00413.x

- Becerra JCL, Sieber R, Martinetti G, Costa ST, Meylan P, Bernasconi E. Infection of the central nervous system caused by varicella zoster virus reactivation: a retrospective case series study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;17(7):e529-e534. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.01.031

- Fadhel M, Campbell N, Patel S, et al. Varicella Zoster Meningitis with Hypoglycorrhachia on Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis in a Young Immunocompetent Host without a Rash. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:701-704. doi:10.12659/AJCR.915300

- Kennedy PGE, Gershon AA. Clinical Features of Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection. Viruses. 2018;10(11):E609. doi:10.3390/v10110609

- Hersi K, Gonzalez FJ, Kondamudi NP. Meningitis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed July 24, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/

- Alvarez JC, Alvarez J, Tinoco J, et al. Varicella-Zoster Virus Meningitis and Encephalitis: An Understated Cause of Central Nervous System Infections. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11583. doi:10.7759/cureus.11583

- Grahn A, Studahl M. Varicella-zoster virus infections of the central nervous system – Prognosis, diagnostics and treatment. Journal of Infection. 2015;71(3):281-293. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2015.06.004

- Gnoni M, Zaheer K, Vasser MM, et al. Varicella Zoster aseptic meningitis: Report of an atypical case in an immunocompetent patient treated with oral valacyclovir. IDCases. 2018;13:e00446. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2018.e00446