Approximately 25% of patients with NSTEMI have an acute coronary occlusion; the STEMI/NSTEMI paradigm can be misleading.

Case

A 52-year-old man presented to the ED with sudden onset sharp chest pain radiating down both arms with associated tingling. He reported the pain began suddenly while he was repairing his porch. He continued to report chest pain but was nontoxic appearing and had normal vital signs aside from bradycardia.

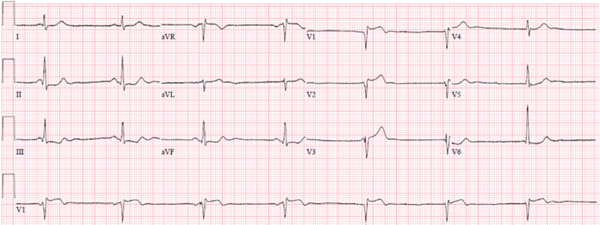

A prehospital ECG showed sinus bradycardia with poor-R wave progression; ≤ 1 mm ST elevation in V1-V3 with reciprocal ST depressions (STD) in II, III, and aVF; and large T-waves in V3-V4 suspicious for hyperacute T-waves.

Image 1. Prehospital EKG

A point-of-care ultrasound did not identify a pericardial effusion but did reveal anterior wall hypokinesis. Initial labs were normal except for a lactate of 2.66 mmol/L. His initial troponin T was < 0.01 ng/mL.

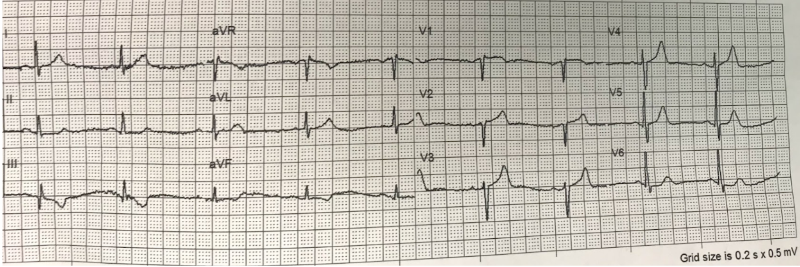

A second ECG performed 10 minutes after the initial study revealed sinus bradycardia with resolving hyper acute T-waves in the anterolateral leads and persistent STD in leads II, III, and aVF.

Image 2. First In-Hospital EKG

Cardiology was consulted for emergent percutaneous intervention (PCI); however, the catheterization lab was not activated, as the ECG findings did not meet STEMI criteria (discussed below).

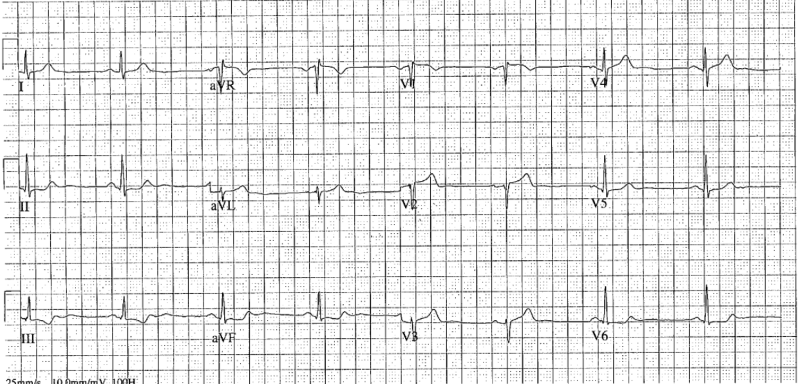

An additional ECG was performed after another 10 minutes. Findings included sinus bradycardia and further progression of STE in V1-V3, with persistent STD in II, III, aVF, V5-V6.

Image 3. Repeat In-Hospital EKG

Careful measurement of V1 and V2 reveals 1.5 mm of elevation at the J-point, with V3 having 1.0 mm of elevation, which does not meet STEMI criteria.

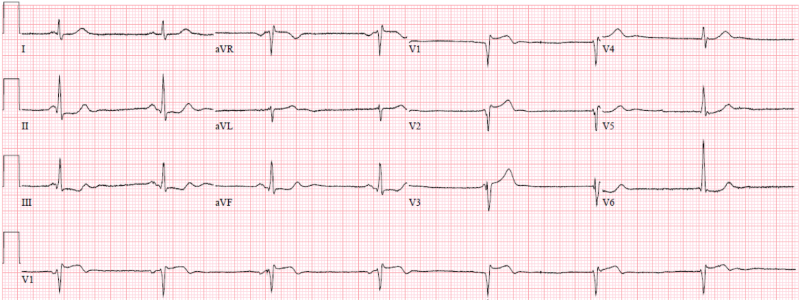

While Cardiology discussed the case, the patient became unresponsive and was found to be in ventricular tachycardia. After one round of CPR and defibrillation, return of spontaneous circulation was achieved, and the rhythm returned to sinus bradycardia. The patient received heparin and amiodarone and was intubated for airway protection. Given findings suggestive of myocardial ischemia subsequent cardiac arrest due to ventricular tachycardia, Cardiology agreed to take him to the catheterization lab for coronary angiography. He was found to have a 100% proximal LAD lesion with acute thrombus. He successfully underwent PCI with a single drug-eluting stent placed, resulting in normal flow.

A repeat troponin obtained 2.5 hours after the initial undetectable measurement resulted in 3.65 ng/mL, which would ultimately peak 4.5 hours later at 8.47 ng/mL, representing a large myocardial infarction. Formal echocardiography performed 12 hours later revealed an EF of 45-50% with severe hypokinesis of the anterior wall, septum, and apex without LV aneurysm.

The patient was extubated 16 hours after presentation and was neurologically intact. He remained hospitalized for 6 days and was discharged after an uncomplicated course.

Discussion

This patient presented with sudden-onset chest pain while performing strenuous activity. The onset, timing, and description of the pain warrants investigation of ACS. The pre-hospital ECG and initial ED ECG are highly suspicious for myocardial ischemia and injury; however, they do not meet STEMI criteria:

- Males age 40 or older: >2.0 mm of STE in leads V2 and V3 and >1.0 mm in all other leads

- Males < 40 years old: 2.5 mm of STE in leads V2-V3

- Women (any age): 1.5 mm STE in leads V2-V3

Classically, STEMI is considered to represent acute coronary occlusion syndromes. However, it has been demonstrated that at least 25% of patients with NSTEMI are found to have ACO on cardiac catheterization. When compared to NSTEMI patients with ACO, NSTEMI patients with ACO demonstrate higher short-term and long-term mortality. Unfortunately, there is no perfect stratification tool or mechanism to identify these patients with ACO, which often delays cardiac catheterization and may adversely affect their prognosis.1-6 This case report highlights this challenge by describing a patient with an LAD occlusion despite lack of STEMI criteria on initial ECGs and cardiac arrest in the setting of delay to cardiac catheterization.7 This case also highlights the current indications for emergent (<2 hr) angiography for NSTEMI patients with ischemia refractory to medical management (which, importantly, does not include opioids), ischemia with cardiogenic shock, or ischemia with electrical instability.7

In this case, serial ECGs helped to demonstrate an evolving pattern of ischemia. Had they not been performed, definitive management may have been delayed.

In addition to serial ECGs and the clinical features above, other adjuncts to the decision to perform emergent reperfusion therapy may include additional ECG leads (right sided, posterior, etc.), troponin, echocardiogram for the presence of wall motion abnormalities, and potentially even emergent CT coronary angiogram.

Teaching Points

- Approximately 25% of patients with NSTEMI have an acute coronary occlusion; the STEMI/NSTEMI paradigm can be misleading.

- Serial ECGs are invaluable in making the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome, especially ACO where dynamic changes may be prevalent.

- Conventional troponin tests take 4-6 hours to manifest in the serum; patients may require more urgent or emergent catheterization and angiography before the troponin becomes positive - thus troponin should not be relied upon to make the diagnosis of OMI.

- Consider serial ECGs, bedside echocardiography looking for regional wall motion abnormality, and other adjunctive tests when there is high concern for OMI.

References

- Khan AR, Golwala H, Tripathi A, et al. Impact of total occlusion of culprit artery in acute non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(41): 3082-3089.

- Hillinger P, Strebel I, Abächerli R, et al. Prospective validation of current quantitative electrocardiographic criteria for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2019;292:1-12.

- Aslanger EK, Yıldırımtürk Ö, Şimşek B, et al. DIagnostic accuracy oF electrocardiogram for acute coronary OCClUsion resuLTing in myocardial infarction (DIFOCCULT Study). Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;30:100603.

- Meyers HP, Bracey A, Lee D, et al. Comparison of the ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) vs. NSTEMI and Occlusion MI (OMI) vs. NOMI Paradigms of Acute MI. J Emerg Med. 2021;60(3):273-284.

- Meyers HP, Smith SW. Prospective, real-world evidence showing the gap between ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and occlusion MI (OMI). Int J Cardiol. 2019;293:48-49.

- Meyers HP, Weingart SD, Smith SW. The OMI Manifesto [Internet]. Dr. Smith's ECG Blog. 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 26];Available from: http://hqmeded-ecg.blogspot.com/2018/04/the-omimanifesto.html.

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.