Influenza is a common viral respiratory illness; however, in certain patient populations it can lead to more severe manifestations—including extrapulmonary complications. Patients at increased risk include children, older adults, and those who are immunocompromised.

Case Report

A 31-year-old female with a past medical history of Addison’s disease presented to the ED with altered mental status. She was febrile, tachycardic, and unable to follow commands. Initial evaluation demonstrated hyponatremia, positive influenza A nasal swab, and cerebral edema on head CT. Initial evaluation was suspicious for Influenza A encephalitis.

The patient was started on normal saline, prophylactic antibiotics, and stress steroids. Further evaluation with head MRI showed areas of acute infarction in splenium of corpus callosum and deep parietal white matter bilaterally, and areas of increased signal on FLAIR weighted images. This led to the patient’s transfer to a tertiary care facility, where she received antivirals and supportive care. After 3 days, she was able to be discharged home with no lingering neurologic deficits.

Significance

Physicians should recognize influenza encephalitis as a possible cause of altered mental status during influenza season. Furthermore, it is important to recognize Addison’s disease as an increased risk for extrapulmonary manifestations of influenza.

Introduction

Influenza A is a common cause of respiratory illness that is typically self-limiting. However, in immunocompromised patients, influenza A can be more severe and lead to extrapulmonary manifestations such as encephalitis.1 Influenza A encephalitis cases are usually seen in children and rarely does influenza cause cases of encephalitis in immunocompetent adults.2 Adults affected by influenza A encephalitis typically recover but it can lead to lasting neurologic deficits.2

Addison’s disease is a rare condition of adrenal insufficiency in which there is an inability to create glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and androgens by the adrenal cortex. The prevalence is estimated to be around 5 new cases/million/year.3 Typically, Addison’s disease presents with symptoms such as: fatigue, weakness, lethargy, muscle cramps, gastrointestinal complaints and hypotension. Addison’s disease has several causes including autoimmune, infectious, neoplastic, and surgical.3 Although not considered an immunocompromised state, patients with Addison’s disease are considered clinically vulnerable.4 Addison’s disease has been shown to have a two-fold risk ratio for death and five times higher mortality rate from infections.4 This increased morbidity and mortality is thought to be due to adrenal crisis caused by acute illness3 and impacted natural killer cell cytotoxicity.4

Though uncommon, influenza can lead to more severe sequalae such as encephalitis and should be considered in patients presenting with neurologic symptoms during influenza season. Further, while not considered an immunocompromised condition, it is important to consider adrenal insufficiency as a risk for increased severity of illness and begin prompt treatment to avoid adrenal crisis.

Case Presentation

This is a 31-year-old female who presents via EMS to the Emergency Department for altered mental status and influenza like illness.

- HPI: Patient’s historian is her partner. He reports she has not been feeling well for the past couple days. She has not been eating or drinking much. She then began acting strangely and was not following commands which prompted her partner to call EMS. He notes she has Addison’s disease for which she takes steroids daily. He does not recall her last known well.

- No Review of Systems performed due to altered mental status.

- Past Medical History: Addison’s disease controlled with daily steroids

- Past Surgical History: none

- Fam History: none

- Social History: no alcohol, no smoking, no substance use

- Allergies: none

- Medications: prednisone - 5 mg in morning, 1 mg in afternoon, florinef (mineralocorticoid) - 0.1 mg daily

Physical Exam

Vitals: 100.5, 107, 115/82, 18, 100%

Physical Exam revealed an ill appearing woman, with no scleral icterus, intact extraocular movements, no nystagmus and pupils equal and reactive to light. She was tachycardic but had no murmurs. She was not in acute respiratory distress and had no wheezes or rales. Her abdomen was soft and nontender. She had no cervical neck rigidity. She did not exhibit any abnormal muscle tone or seizure activity. She did not exhibit any facial asymmetry. She did appear confused and would inconsistently follow commands. Her GCS eye score was 4, verbal 3, and motor 5.

Labs/ Imaging

Labs done upon initial evaluation included:

- Cortisol: 150

- Viral Swab: flu A +, flu B –, RSV –, COVID –

- CMP: Na 126, K 3.7, Cl 96, CO2 20, Anion Gap 10, glucose 194, BUN 10, Cr 0.84, BUN/Cr 11.9

- Lactic Acid: 1.8

- CBC: WBC 9.24, RBC 5.05, Hgb 14.8, hct 41.5

- Blood cultures: resulted negative after 120 hours

- TSH: 3.543 #1 at 4:50 pm

- EKG: sinus at 90, normal intervals, no ST-T changes

- CXR: no acute cardiopulmonary disease

Figure 1. CT head read as small ventricles, effacement of third ventricle and bilateral cortical sulci, suggestive of cerebral edema. No herniation or midline shift. No acute ischemic process or intracranial process.

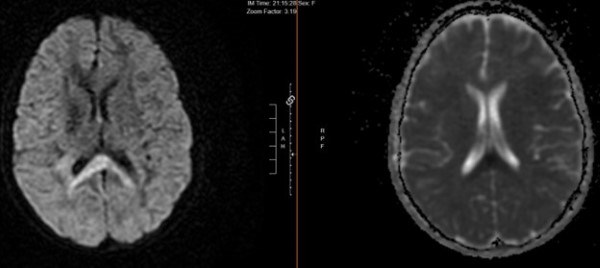

Figure 2. MR Brain w/w/o contrast read as areas of acute infarction in splenium of corpus callosum and deep parietal white matter bilaterally. Areas of increased signal on FLAIR weighted images are suspicious for encephalitis/meningitis given history.

Differential after Initial Evaluation

Based on the initial evaluation and physical exam the differential included:

- Influenza encephalitis

- Hyponatremia

- Meningitis

- Toxicity from unknown substance

Following evaluation included:

- CSF:

- Cell Count / Differential

- Tube 1: 284 RBC, 1 nucleated cell, 23% neutrophils, 66% lymphocytes, 11% monocytes

- Tube 4: 1 RBC, 2 nucleated cells, 83% lymphocytes, 16% monocytes, 1% neutrophils

- Gram stain/ culture negative/ no growth

- CSF glucose 59 (normal), protein 28 (normal)

- BioFire NAAT CSF negative for: cryptococcus gattii, CMV, enterovirus, Ecoli K1, H flu, HSV ½, HHV6, Human Parechovirus, listeria monocytogenes, strep pneumo, VZV

- Cell Count / Differential

- TSH: 1.209 #2 at 8:30pm

- Urine Na: 117

- Na: 130 (This repeat sodium was after 1 L of Normal Saline)

- Blood osmolality: 269

Diagnosis: Influenza A encephalitis

Management

Initially the patient was given 1 L NS for hyponatremia, which improved the sodium from 117 to 130. The initial evaluation led to a consult with Neurology, who suggested an MRI as well as a lumbar puncture. For management with the history of Addison’s disease, Endocrinology suggested stress steroids. Teleneurology also recommended beginning antibiotics prophylactically. She was started on vancomycin and ceftriaxone.

Due to the patient’s age and the infarcts seen on MRI, Neurology recommended transfer to a tertiary care facility.

Outcome

The patient spent 3 days at a tertiary center, where she received supportive care and antiviral influenza treatment. She was able to be discharged home and resumed her normal activities with no neurologic deficits.

Discussion

The diagnosis of Influenza A encephalitis is uncommon, especially in immunocompetent people. Typically, influenza causes more severe complications in older adults or those who are immunocompromised. Extra-pulmonary complications of influenza include myocarditis, ischemic heart disease, encephalitis, Guillain-Barre, myopathy, and others.5 Most cases of influenza encephalitis occur in children.1 It has been shown that in patients with Influenza A encephalitis, 79% survive, but 25% had neurologic deficits including motor weakness and cognitive deficits.5

The diagnosis of influenza encephalitis is difficult given the lack of validated diagnostic criteria. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with fever and neurologic symptoms, especially during influenza season.6 There are no clear diagnostics but work up includes nasopharyngeal swab/ culture, blood work, CT, MRI, and lumbar puncture.6 In those who had brain CT, 39% showed acute changes, 50% were normal, and 11% showed chronic changes.5 All the patients who completed an MRI had abnormal findings.5 Lumbar puncture findings including pleocytosis (17%), elevated protein (17%), and was normal in most cases (46%).5 In this patient, CT and MRI both showed acute findings, but the CSF findings were normal. Brain MRI is more specific and the preferred method of diagnosis of encephalitis.6 CSF fluid can be analyzed for influenza with PCR but has only been found to be positive in 16% of patients.6

A preventative measure from development of severe influenza illness is the influenza vaccine. Our patient had unknown vaccination status, and if they did not receive the annual influenza vaccine it may have also contributed to development of encephalitis. Influenza vaccination has an efficacy from 59-83%.6

There is no standard therapy for influenza encephalitis management.6 Treatment for influenza encephalitis mainly consists of supportive care, antivirals (such as neuraminidase inhibitors and amantadine), glucocorticoids, antiepileptics in specific cases, and immunomodulatory medications such as gamma globulins and alpha interferon.6 In the case of our patient, antibiotics were initiated prophylactically while test results were pending, and they were also started on antivirals. They also received supportive care. The role of glucocorticoids in this patient were more specific for Addison’s disease.

For our patient, it is likely that Addison’s disease played a role in the development of the severe symptoms. Studies have shown that Addison’s disease decreases the immune response and the ability to fight infection, which may have contributed to this patient’s severe symptoms.4 With a reduced immune response, the patient may have developed viral CNS invasion or increased cytokine release.6

The patient’s hyponatremia may have further exacerbated the cerebral edema seen on imaging. The hyponatremia may have been caused by a degree of adrenal crisis; however, the patient was not hyperkalemic and had normal glucose, so it is more likely that dehydration was the cause, but it remains important to consider stress steroids in patients with Addison’s disease to prevent adrenal crisis.7

Take-Home Points

This case highlights the need for including influenza encephalitis on the differential in presentations of altered mental status during influenza season. It is also important to perform comprehensive work up for encephalitis due to the lack of diagnostic criteria.

This case also highlights that severity of illness can be increased in those with Addison’s disease, and the need to initiate steroid management to prevent Addisonian Crisis.

References

- Mastrolia MV, Rubino C, Resti M, Trapani S, Galli L. Characteristics and outcome of influenza-associated encephalopathy/encephalitis among children in a tertiary pediatric hospital in Italy, 2017–2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1012.

- Edet A, Ku K, Guzman I, Dargham HA. Acute Influenza Encephalitis/Encephalopathy Associated with Influenza A in an Incompetent Adult. Case Rep Crit Care. 2020:6616805.

- Betterle C, Presotto F, Furmaniak J. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of Addison’s disease in adults. J Endocrinol Invest. 2019;42(12):1407-1433.

- Bancos I, Hazeldine J, Chortis V, Hampson P, Taylor AE, Lord JM, Arlt W. Primary adrenal insufficiency is associated with impaired natural killer cell function: a potential link to increased mortality. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;6(4):471-480.

- Sellers SA, Hagan RS, Hayden FG, Fischer II WA. The hidden burden of influenza: A review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2017;11(5):372-393.

- Meijer WJ, Linn FHH, Wensing AMJ, et al. Acute influenza virus-associated encephalitis and encephalopathy in adults: a challenging diagnosis. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3(6):e005076.

- Kapadia S, Saad A. Infections in Patients with Addison's Disease: Considerations in Primary Care. Ann Clin Case Rep. 2023;8:2493.