You are in the emergency department and a 1-month old female presents with her father for dyspnea.

According to the father, she was being removed from the bath the night before when she slipped out of his hands, hitting her face on the nearby counter. He was able to grab her by the arm before she hit the ground. When asked why he did not seek medical care, he stated “I thought she was fine.” Physical exam showed an abrasion to the bridge of the nose with underlying ecchymosis, ecchymosis circumferentially around the left arm, and an abrasion to the inferior gum line. Her lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally with no tachypnea or retractions. What would you do if this patient presented to your ED?

With an overflow of patients, the ED can be chaotic. The combination of social distancing, abundant caution, and fear of COVID-19 have contributed to a drop in our pediatric census. In a recent New York Times article, author Nikita Stewart reported, "In the first 8 weeks of spring 2019, New York City's child welfare agency received an average of 1,374 cases of abuse or neglect to investigate each week. In the same period this year, that number fell to 672, a decline of 51%."1 With the added physical and mental stress of a pandemic affecting parents all over the U.S., it is interesting to note that we have not seen an increase in reported abuse and neglect. Has abuse really diminished? Or does the decrease in pediatric presentations mean fewer children are receiving medical care and appropriately indicated work-ups? Before the pandemic it was estimated that between 2-10% of children visiting the ED were victims of child abuse or neglect.2 In the coming months and year we must be on the lookout for these patients and have a high index of suspicion for child abuse.

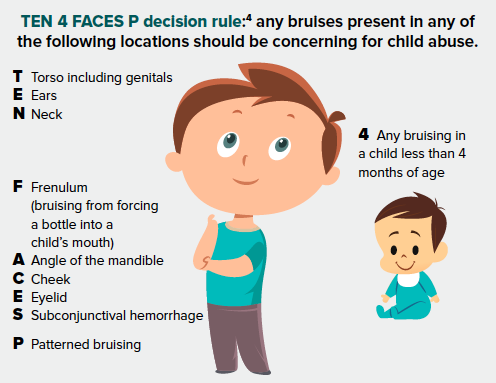

As emergency physicians, we must be vigilant for these patients. A study of 44 children who died of child abuse showed that 20% of them were evaluated by a physician within a month prior to their death. It was determined that 71% of those evaluations were in an ED.2 At times we are the only medical care these high-risk patients receive and possibly their only chance for intervention. How, then, do we get better? The most important part of these evaluations is the physical exam. Although the caretaker can be dishonest, your physical exam is an objective measure of truth. In a study with 200 infants who had experienced confirmed severe abuse, 55 (27.5%) had a sentinel injury before the episode of severe abuse. Of the 55, 80% had bruising and 11% had intraoral injury, often bruising to their frenulum.3 All children under one year of age, regardless of chief complaint, should be placed in a gown to facilitate a full-body exam. This is an easy way to facilitate more thorough examinations in a chaotic emergency department. Bruising should be used as a screening tool for child abuse, and careful attention should be paid to location of the bruise, age of the child, and distribution of ecchymosis. The TEN 4 FACES P decision rule can be a useful clinical aide when suspecting abuse.

Location

Bruises that were predictive of abuse were located on the torso, ear, or neck of a child younger than 4 years of age. Bruising in any region on an infant younger than 4 months of age was also predictive. The sensitivity of this decision rule was 97% and the specificity was 84% for predicting abuse.4

Patient age

Those who don’t cruise rarely bruise.5 One study on prevalence of bruising in infants in the pediatric ED found a significant difference in bruise rates for infants younger than 5 months old compared to those older than 5 months old. The prevalence of bruising for infants 5 months and younger, in comparison to those older than 5 months, was 1.3% to 6.4%.6 Infants younger than 5 months old should not present to your ED with bruising. As soon as the child starts to crawl or walk, bruising will become more common. These bruises should not be located in the aforementioned locations.

Patterned bruising

Patterned bruising should always be concerning. Hand imprints are common, as are the imprints of objects like belts, cords, shoes, and kitchen utensils.7 Look for bruising that is consistent with the items mentioned above.

Bruise age

What if the bruise looks old? In a study of fifty children with accidental bruises, EM pediatricians accurately estimated bruise age (within 24 hours of the actual age) 47.6% of the time.8 Your judgment alone is not a reliable enough way to determine whether a bruise is younger than 24 hours old.

Is non-accidental trauma the only cause of bruising? Of course not. Patients with concerning bruising should be admitted to the hospital for a full workup, including further testing for other causes of bruising such as bleeding diatheses, coagulopathy, infection, thrombocytopenia, and other etiologies. We must not be afraid to advocate for children and report possible child abuse. A bruising prevalence study conducted in three pediatric EDs found that only 23% of pediatric patients found with bruising (88/2344) had an abuse evaluation. According to the author this was far fewer than expected.6 Although a bruise increased the threshold for evaluation, it was not enough. Most children with suspicious bruising should be reported to the proper authorities and evaluated for further injury. It is more acceptable to report child abuse and be wrong than it is to not report and risk a child dying or sustaining serious injuries from child abuse.

In the case mentioned at the beginning of this article, the patient was admitted for further evaluation and found to have multiple new and healing rib fractures, retinal hemorrhages, and a subdural hemorrhage. All findings were consistent with non-accidental trauma. Although with younger children illness and injury is not always obvious, we must stay vigilant of the bruise, and keep non-accidental trauma on our minds and in our differential. If you do not look for it, you will never find it.

References

- Stewart, N. Child Abuse Cases Drop 51 Percent. Authorities Are Very Worried. The New York Times. [Internet]. 2002 Jun 9.

- Leetch AN, Leipsic J, Woolridge DP. Evaluation of Child Maltreatment in the Emergency Department Setting: An Overview for Behavioral Health Providers. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2015;24(1):41-64. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.09.006

- Sheets LK, Leach ME, Koszewski IJ, Lessmeier AM, Nugent M, Simpson P. Sentinel injuries in infants evaluated for child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):701-707. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2780

- Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Aldridge S, O’Flynn J, Lorenz DJ. Bruising characteristics discriminating physical child abuse from accidental trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):67-74. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3632

- Sugar NF, Taylor JA, Feldman KW. Bruises in Infants and Toddlers Those Who Don’t Cruise Rarely Bruise. Vol 153.; 1999.

- Pierce MC, Magana JN, Kaczor K, et al. The Prevalence of Bruising among Infants in Pediatric Emergency Departments Presented as a poster at the Ray E. Helfer Society annual meeting, April 2013, Sonoma, CA. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2016;67(1):1-8. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.06.021

- Harris TS. Bruises in Children: Normal or Child Abuse? Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2010;24(4):216-221. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.03.007

- Bariciak ED, Plint AC, Gaboury I, Bennett S. Dating of bruises in children: an assessment of physician accuracy. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):804-807. doi:10.1542/peds.112.4.804