Can't-intubate/can't-ventilate scenarios are critical, and the difficulty ramps up when your patient is a young child.

Case Presentation

During a previously quiet Saturday morning, EMS reports they are en route with a 3-year-old male choking on an unknown foreign body. They are 3-5 minutes out, and the patient is saturating 95% on room air, but in obvious distress.

When the patient arrives, he is in respiratory distress, tripoding, and not tolerating oral secretions. He is constantly moving, coughing, and trying to find a position of comfort. Staff begin attempting back blows while getting the patient connected to the monitor. Mom arrives with the patient and says he was found playing in a bag of makeup.

Case Questions

- What do you get ready to manage this patient before EMS arrives?

- When are back blows most effective for an airway foreign body?

- What if you can’t intubate, can’t ventilate?

Management

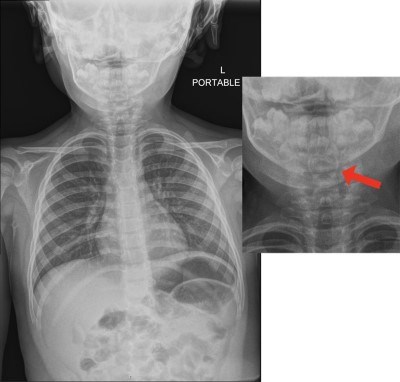

Prior to administering any medications, video laryngoscope was set up in preparation for visualization and removal of a foreign body and for possible endotracheal intubation. In addition to this, the equipment needed for a needle cricothyrotomy was prepared as a backup. A chest x-ray showed a small circular foreign body just superior to the vocal cords (Image 1), although later reported as normal by radiology.

Image 1. CXR with nearly radio-lucent round foreign body sitting at the level of the vocal cords

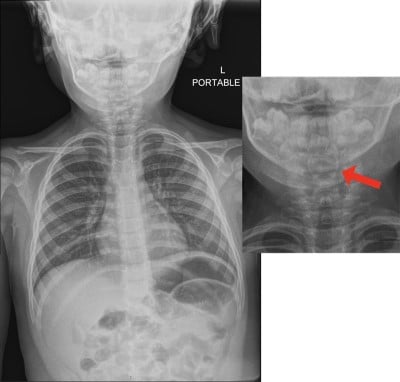

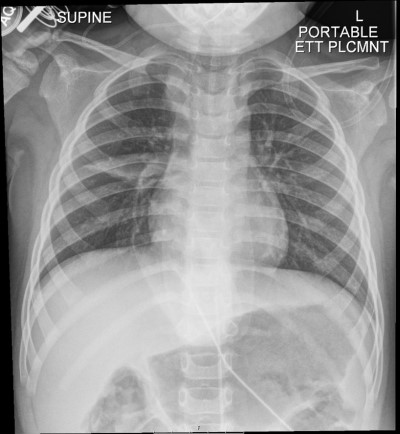

Ketamine and midazolam were administered, and the patient was placed in partial supine position. Video laryngoscope revealed a lip balm cap sitting at the top of the patient’s vocal cords. As the patient was placed further in the supine position, the lip balm cap fell posterior to the vocal cords. Since the foreign body was no longer obstructing the vocal cords, rocuronium was administered and the patient was successfully endotracheally intubated. After endotracheal intubation, the lip balm cap was removed with alligator forceps (Images 2 and 3). Repeat chest Xray confirmed appropriate tube-placement and no additional foreign bodies or pulmonary findings (Image 4).

Image 2. McGill forceps on top, shown for size comparison with alligator forceps below

Image 3. Lip balm cap that was partially occluding the airway of the patient

Image 4. Post intubation x-ray

The patient tolerated the intubation well, but developed coarse tight breath sounds as a result of the event. Glycopyrrolate and dexamethasone were administered to reduce secretions and decrease the inflammatory response. Anesthesia was at bedside and aided with rocuronium reversal with sugammadex. The patient was extubated after approximately 1 hour. The patient was then observed in the ED for 4 hours following extubation. After passing a PO challenge, he was discharged home with family.

CASE DISCUSSION

What do you get ready to manage this patient before EMS arrives?

This case highlights the importance of having a strategy that includes a backup plan to manage a potentially difficult airway, including not just equipment, but also interdisciplinary care teams for a difficult airway (anesthesia and surgery). This case could have quickly evolved into a can’t-intubate/can’t-ventilate scenario with devastating consequences if endotracheal intubation was unsuccessful or if the foreign body obstructed passage of an ET tube.

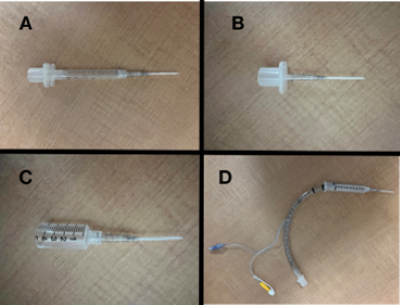

Given the patient’s young age and small upper airway, needle cricothyrotomy would have been the required backup procedure in a can’t-intubate/can’t-ventilate scenario. Generally, in patients younger than 8 years old, a needle cricothyrotomy would be performed as opposed to standard cricothyrotomy.1,2 Standard cricothyrotomy is contraindicated in younger patients due to theoretically increased risk of subglottic stenosis3 and small cricothyroid membrane.4 If time allows before managing a difficult airway, it is recommended to identify the cricothyroid membrane via palpation or with ultrasound to prevent device misplacement, injury to other structures, and airway trauma.3 There are several options to set up a needle cricothyrotomy (Image 5).

Image 5-A. Large-bore angiocath (preferably a 14 or 16 gauge catheter) connected to a 3 cc syringe and a size 7 ET tube connector. The size-7 ET tube adapter should fit snug in the top of the syringe with the plunger removed.

Image 5-B. Large-bore angiocath connected to a size 3 ET tube connector. The 3-0 ET tube adapter should fit tightly inside the luer lock connector of a standard angiocath device.

Image 5-C. 10 cc syringe that was cut in half and connected to a large bore angiocath. The outer diameter of many 10cc syringes is 15mm, thus fitting the universal outlet port of BVM or other airway equipment.

Image 5-D. Large-bore angiocath connected to a 10 cc syringe, inside of which is a 7.5 ET tube with the balloon inflated. This technique allows for variation in sizes between vendors of equipment but adds complexity and resistance due to length of tubing.

When are back blows most effective for an airway foreign body?

Back blows are still taught as part of a BLS technique to dislodge a foreign body in a pediatric patient under the age of 12 months, there may be some benefit if the child is small enough to hold in a head-down position. However, it is recommended not to perform back blows if the patient is still able to cough or cry.5,6 In these cases, the obstruction is incomplete, and the patient may be able to dislodge the object by coughing. Although that did not occur in this case, forceful inhalation could allow for aspiration and complete occlusion of a previously partial airway obstruction.

What if you can't intubate/can't ventilate?

Steps to perform a needle cricothyroidotomy3

- Stabilizing the larynx with your nondominant hand, identify cricothyroid membrane, apply tension to skin over the cricothyroid membrane by stretching skin in vertical direction.

- Use a 3 cc or 10 cc syringe filled with water or saline attached to an angiocatheter and puncture skin over the cricothyroid membrane, aiming in a caudal direction at a 30-45 degree angle, apply negative pressure until air bubbles are detected in the syringe, stop advancing the needle.

- Advance the angiocatheter and remove the needle.

- Confirm intratracheal placement by aspirating air again.

- Hold the angiocatheter at all times; do not rely on sutures.

- Connect the catheter to high-pressure tubing (jet ventilation) or a bag valve mask with 100% oxygen. Ventilate at a rate of 10-12 breaths per minute, using an I: E ratio of approximately 1:4.

It is important to keep in mind that jet ventilation requires an unobstructed upper airway to avoid hypercapnia and allow for expiration. Jet ventilation is not recommended for long term ventilation.3 If using a BVM to deliver breaths, the physician needs to consider occluding or covering the pop off valve (if present) to allow delivery of high-pressure oxygen due to the narrowness of the angiocatheter.

Complications

A case by Okada et al. in 2017 describes a 3-year-old boy in cardiac arrest secondary to an upper airway obstruction from idiopathic anaphylaxis or acquired angioedema that led to a cannot intubate, cannot ventilate scenario. Video laryngoscopy failed and needle cricothyrotomy was considered, but the physicians were unable to identify the proper angle to insert the needle due to lack of space (ie, small pediatric neck with a lot of subcutaneous fatty tissue). Physicians were concerned the posterior trachea would have been inadvertently punctured. In this case they proceeded to standard cricothyrotomy with a cricothyrotomy kit. This failed, as the space between the cricothyroid cartilages was smaller than the cannula in the kit and the cannula kinked. Emergent tracheostomy was attempted and finally successful. Unfortunately, the patient died, and autopsy revealed the cricothyroid membrane was only 3 mm in size.7

Most common complications during cricothyrotomy include bleeding, injury to tracheal cartilage, perforation of trachea, false tract creation, infection, subglottic stenosis.3

Neonates are particularly difficult to obtain emergent airway access due to their smaller anatomy. Even with proper positioning and placing their necks into extension, successfully palpating the cricothyroid membrane can be difficult. Once the cricothyroid membrane is identified, the steep angle needed to enter the membrane increases the risk of posterior tracheal penetration.7

If the physician is able to successfully perform a needle cricothyrotomy, jet ventilation carries complications including emphysema, pneumothorax, lung injury.1 Some experts even suggest that surgical cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy may be preferred in children younger than 6 years old because the trachea is so small and chance of posterior tracheal wall injury is high, but this is controversial.1 In neonates, the mean length of the cricothyroid membrane is 2.6 ± 0.7 mm and a width of 3.0 ± 0.63 mm, compared to the average adult cricothyroid membrane 13.7 mm long and 12.4 mm wide.8

The Difficult Airway Society guidelines suggest that standard cricothyrotomy be performed if needle cricothyrotomy fails.1 If ENT is emergently available, emergent tracheostomy can be considered as a first step. Emergent tracheostomy at the proximal trachea with scalpel, finger, bougie technique is another option to be considered if other options fail.7

Take-Home Points

FBAO is an anxiety-provoking clinical encounter, especially in a pediatric patient. Planning ahead by having people and tools available to support anticipated care – including potential complications – is important, as is practicing for and simulating these types of high-risk situations.

One tool that was particularly useful in this case was the alligator forceps that allowed for removal of the foreign body. Often McGill forceps are considered for airway use, but in this pediatric patient, this tool was simply too large to work with the small airway and space available (Image 2).

Additionally, the availability of the anesthesia team to support the reversal of rocuronium with sugammadex allowed this patient to be extubated in the ED, saving an ICU admission.

References

- Black AE, Flynn PE, Smith HL, Thomas ML, Wilkinson KA, for the Association of Pediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Development of a guideline for the management of the unanticipated difficult airway in pediatric practice. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(4):346-362.

- Berger-Estilita J, Wenzel V, Luedi MM, Riva T. A Primer for Pediatric Emergency Front-of-the-Neck Access. A A Pract. 2021;15(4):e01444.

- McKenna P, Desai NM, Tariq A, Morley EJ. Cricothyrotomy. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; February 4, 2023.

- Stern J, Pozun A. Pediatric Procedural Sedation. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 22, 2023.

- American Heart Association. Basic Life Support: Provider Manual. 2020.

- Habrat D. How to treat the choking conscious infant. Merck Manual Professional Edition. July 13, 2022.

- Okada Y, Ishii W, Sato N, Kotani H, Iiduka R. Management of pediatric 'cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate'. Acute Med Surg. 2017;4(4):462-466.

- Navsa N, Tossel G, Boon JM. Dimensions of the neonatal cricothyroid membrane - how feasible is a surgical cricothyroidotomy?. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(5):402-406.