Back in the good ol' days, it was said you can never go wrong with spending money on your education. And then came student loan debt... Have things ever been worse? Can they get better?

I never trusted the “good old days.” We idealize the past and assume the future will always progressively get worse and worse until the apocalypse hits, but maybe this attitude or perspective is more a reflection of human nature than an accurate comparison of today vs. yesterday. Speaking of yesteryear, can you guess which “modern-day” figure spoke the following quote?

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.”

This was actually a quote from Socrates, who lived in 400 BC. So when were the “good old days,” anyway? Is yesterday always better than today? I am not sure. However, when it comes to student loans, I can objectively say today has never been worse.

Student Debt: Grim Picture

According to an analysis completed by the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis at the beginning of 2018, 44 million Americans owe a collective $1.5 trillion in student loan debt.1 That is more money than the entire national debt of Greece and Spain combined!2 Americans hold more student loan debt than credit card debt, making it the second largest expense behind owning a home.3 We all know credit card debt is bad, but student loan debt has got it beat by about $620 billion.4

There was a time when the ethos in America was that you could never go wrong with spending more money on your education. Keep in mind that was probably advice given to you by an older generation who lived in a different economic world when the cost of education was far less and the American economy was growing as much as 5% each year. However, the cost of education has been growing at an unprecedented rate, nearly 8% per year. This is beginning to literally change the culture of the United States and the futures of millions of Americans in a very negative way as people forego buying homes, starting business, getting married, having children, and spending time with family and friends – all to keep up with student loan payments.

The average college graduate owes $37,172 in student loans. That might just sound like the price of a fancy, brand-new car you probably don’t need, but the debt is substantial in comparison to average household income. According to 2015 data from the U.S. Census, the median household income in the United States is $56,516. But remember, household income represents all people living in a single household contributing to taxable income.5 So conceivably, a nice new married couple with a child or two may only be making around $56,516 a year. Having student loans from both mom and dad may represent more than they make annually.

But as physicians, why should we care?

Medical School Debt: Even Worse

Are we average? Are we mortal? There has got to be a reason that everyone’s mom and dad wanted them to become a doctor. We are surely immune from the financial trouble — right? Wrong. The numbers show otherwise, especially when considering the financial woes of student loans for medical students.

According to an analysis of medical student debt published in 2012 by the AAMC, the student loan burden for an American medical student is currently worse than it was 40 years ago. The average medical student in 1978 graduated with about $13,500 in debt, or $46,500 in 2011 dollars, while the average medical student in 2011 graduated with $161,300 in debt. Even after accounting for inflation of the U.S. dollar, that is a nearly 350% increase in medical school debt. This means that from 1978 to 2011, medical student debt has grown at an average rate of 7.8% per year, twice the rate of inflation (which the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows has been lower than 2.5% per year for the past decade).6-7 At its best, the U.S. economy grows about 5% per year; although it’s been a while since we hit those numbers, GDP for 2018 is at 4.2% and has trended near 3% for the past 2 years.8

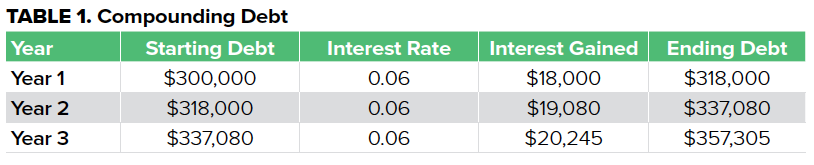

Personally, I now have nearly $300,000 in student loan debt after going through 4 years of college and 4 years of medical school. Bear in mind, I had paid off my overpriced liberal arts undergraduate education before starting medical school. Here is a little math: Let’s imagine that I pay 6% per year in interest on my student loans. I have been told I have a “good” rate.

$300,000 (principal, the total loan money received) x 0.06 (interest rate) = $18,000 (annual interest owed in Year 1)

Therefore, each year, just to keep my loans from compounding (gaining interest on prior interest), I need to come up with $18,000 to stay even.

In 2015, 13.5% of the U.S. population, or 43.1 million people, lived in poverty.3 Depending on family size, if your household comprises fewer than 4 people and your household made less than $18,871, you are in poverty. This means millions of families across America find it difficult to even generate the amount of money I owe on interest payments alone. The government recognizes this and so assists these families, rightfully so, with many programs and benefits. What does the government do for the young student?

Well, there are flexible debt repayment programs that allow us to forego making any payments on our student loans while in residency, which is at least 3 years for any physician. What a nice thing, right? No payments, no worries.

But the interest is compounding. Let’s calculate what I would owe at the end of a 3-year residency if I were to take advantage of the flexible debt repayment program.

Table 1 should make anyone’s jaw clench! So, for me to put my head in the sand for 3 years and have the flexibility of foregoing payments increases my debt an extra $57,000. Thank you, Uncle Sam!

Why not make some payments during residency? According to a survey completed by more than 1,500 residents, the average resident in the U.S. earned about $57,200 in 2017. The average resident simply doesn’t have money to spare to put toward loans. This was not a problem for the average physician a generation or two ago who owed far less in loans than we do now.

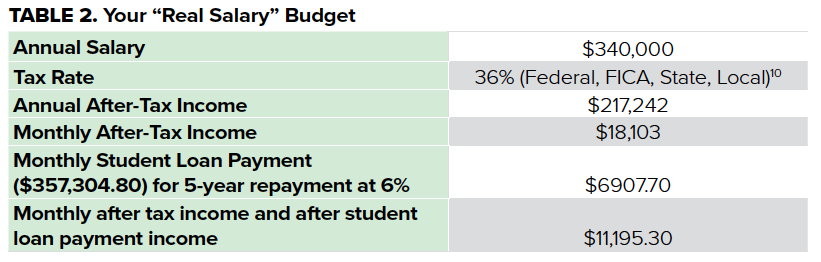

OK, so another round of calculation. Once we start making attending salaries and we have to start making payments on our student loans, how does the budget look then? The average annual salary of an EM doc in the mid-Atlantic was quoted to be $340,000 annually.9 Six figures, baby! Sounds great, but let’s break it down (see Table 2).

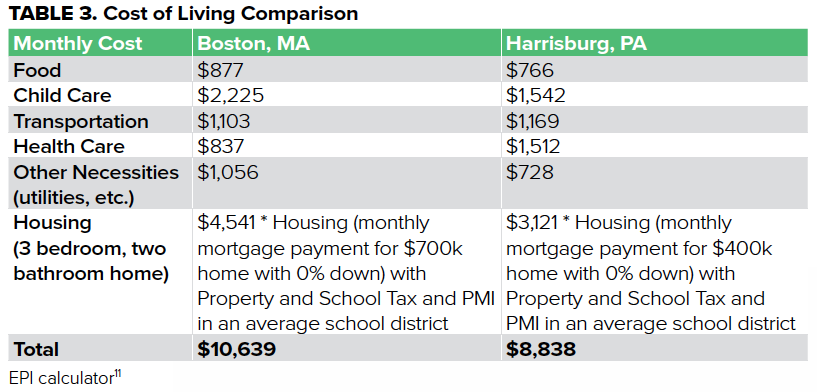

So $11,000 per month take-home salary is the long story short. Is that enough? Consider the EPI calculator, a free online tool that estimates costs of living for many metropolitan areas across the United States.11 Compare the annual cost of living for a family of 4 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania vs. annual cost of living for an urban center like Boston (see Table 3).

There isn’t much money left over. Where are the savings for retirement, your deductible on health insurance, your kid’s college fund, or a vacation? If you weren’t paying nearly $7,000 a month for years on student loans, there would be a lot more room for that.

Implications for the Future

The next generation is beginning to feel the negative financial pressure of this system, and it may begin to scare away good future physicians. Of course, with the aging of the Baby Boomers, there is a need for more physicians than ever before. For example, one AAMC study predicts that by 2025, the U.S. will have a shortage of more than 35,600 primary care physicians.12 This will only get worse under the current economic conditions and trends. So, what’s the point?

The truth is those in other professions are working very hard, too. People are often working multiple jobs, picking up side work, and not taking vacations. And outside the house of medicine, job predictably is not always stable.

Possible Solutions

Student loans are truly burdensome and have never been worse; therefore, we must call for policy changes to improve our financial reality. Although physicians cannot unionize, why can’t we use basic principles of economics to lower our interest rates? Why can’t we collectively consolidate our loans, with one private company, at a low interest rate?

Imagine thousands of physicians approaching one bank with hundreds of millions of dollars of loans requesting a 2% annual interest rate. They make money, we save money. Everyone wins.

With a bit more delayed gratification, your loans can be paid off within 5 years. You may be in your mid- to late 30s when that happens, but the math suddenly gets better after the loans are gone.

EMRA RESOURCES

EMRA members! Don’t forget you have access to special benefits through Doctors Without Quarters, Laurel Road, and Integrated Wealthcare. Check out your benefits page at emra.org!

References

1. Hess A. Here’s how much the average student loan borrower owes when they graduate. CNBC. February 2018.

2. StashLearn. Top 10 Countries with the Largest National Debt-to-GDP in 2018. Accessed August 2018.

3. Friedman Z. Student Loan Debt in 2017: A $1.3 Trillion Crisis. Forbes. February 2017.

4. Student Loan Hero. A Look at the Shocking Student Loan Debt Statistics for 2018. Updated May 2018.

5. Proctor BD, Semega JL, Kollar MA. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015. United States Census Bureau. 2016;P60-256.

6. AAMC. Trends in Cost and Debt at U.S. Medical Schools Using a New Measure of Medical School Cost of Attendance. Analysis in Brief. 2012;12(2).

7. United States Department of Labor. Consumer Price Index. Updated July 2018.

8. Trading Economics. United States GDP Growth Rate 1947-2018. Updated July 2018.

9. Katz B. 2017-2018 Compensation Report for Emergency Physicians Shows Steady Salaries. ACEP Now. Oct. 17, 2017.

10. Smart Asset. Federal Income Tax Calculator. Accessed July 2018.

11. Economic Policy Institute. Family Budget Calculator. Accessed July 2018.

12. Rege A. Average medical school student’s debt in 2014 3.5 times greater than in 1978. Becker’s Hospital Review. May 1, 2017.