Pit vipers, known collectively as crotalids,1 are a group of venomous snakes including copperheads, cottonmouths (water moccasins), and rattlesnakes. In the United States, the smallest of the rattlesnakes is the “pygmy” group. Despite their small size, their venom is a potent hemotoxic that can result in significant morbidity.

CroFab® (generic: crotalidae polyvalent immune fab ovine), also known as FabAV, is frequently used for pit viper envenomations.9 FabAV is derived from the venom of four different North American snakes and has cross-reactivity with a number of species, but there is no well-documented evidence of venom neutralization for the western pygmy rattlesnake.9

We present the case of a moderate pediatric envenomation with a western pygmy rattlesnake resulting in progressive bruising and swelling, successfully treated early with FabAV.

Case

A 7-year-old boy with no past medical history sustained a snakebite of the left foot. He was initially taken to a rural emergency department and was transported by air from there to our satellite hospital. While at the satellite hospital, the patient was nauseous and had swelling and severe pain of the affected extremity. The satellite hospital contacted poison control for consultation with the toxicologist, who recommended antivenom, pain control, and transfer to the main campus.

Background

Western pygmy rattlesnakes (Sistrurus miliarius streckeri) are native to the southeastern United States. They are small even when fully grown, reaching just under 2 feet.2 They inhabit flatwoods, mixed forests, lakes, and marshes across Mississippi, Louisiana, East Texas, extending north into southeastern Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, and southwestern Tennessee.2,3

Western Pygmy Rattlesnake. Photo courtesy of Kory G. Roberts.

It is estimated that about 9,000 people per year suffer a snakebite in the United States, but only five deaths occur annually.6 The vast majority of snakebites in the United States are from pit vipers, of which more than 50 percent occur from rattlesnakes.6 Approximately 25 percent of all pit viper bites in the United States do not result in envenomation and are said to be “dry” bites, or bites that do not contain venom.4,6 In particular, western pygmy rattlesnake envenomations are a rare occurrence, likely due to the secluded nature of the species.3

Crotalid venom consists of a complex mixture of proteins and enzymes that causes local tissue destruction as well as hematologic and systemic effects.1,6 There are more than 50 constituents of crotalid venom, including:

- disintegrins, whose role is to antagonize fibrinogen activation of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, which effectively inhibits platelet aggregation;

- eptifibate, a known antiplatelet;

- phospholipase A2, which is thought to damage platelet membranes, causing destruction and resulting in thrombocytopenia;

- metalloproteases, which result in local tissue destruction and increase permeability as well as hemorrhage;

- C-type lectin-like proteins; and many others.5,6,7

This complex mixture can vary across species, geographic distribution, and by time of year.1 Snakebite venom is often delivered to the subcutaneous tissue. Direct intravenous injection from a snakebite is rare, but when it occurs, it may be fatal.6

Evaluation

Signs and Symptoms

Severe pain and swelling at the site of the bite are common.8 Ecchymosis, fluid-filled or hemorrhagic blisters, and extensive tissue destruction may develop.8 The bite site may become edematous and tense, although compartment syndrome is rare.1,8,21 The affected area should be evaluated every 15 to 30 minutes for swelling, tenderness, and hemorrhagic blebs until the tissue effects have stabilized.1 Systemic toxicity is characterized by a metallic taste, oral paresthesias, tachycardia, hypotension, and anaphylaxis.8

Labs

Patients with possible snakebite envenomation should have a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, prothrombin time, fibrinogen, and creatine kinase. Patients with systemic toxicity or comorbidities may warrant additional tests.1,8 Western pygmy rattlesnake envenomations have a higher incidence of thrombocytopenia and delayed coagulopathy.9 A retrospective chart review of 75 pit viper envenomation patients found that 60 percent of patients with western pygmy rattlesnake envenomations had thrombocytopenia.9 Laboratory studies should be obtained on arrival and repeated in 4 to 8 hours.8 If FabAV is administered, then platelets and fibrinogen should be checked 2 to 3 days after the last FabAV dose and again 5 to 7 days after the last dose.21 Routine measurement of D-dimer is unnecessary, as it does not accurately predict envenomation.1

Imaging

Imaging is not generally necessary but can be considered to exclude other causes of symptomatology (e.g., chest radiography for respiratory distress or retained foreign body).1

Management

Immediately address life-threatening conditions such as airway compromise or hemodynamic instability.1,8

Remove constrictive clothing and jewelry from the affected limb.11,12 Do not use tourniquets or pressure immobilization, as these can cause limb ischemia as well as increase local tissue damage and systemic absorption of the venom.10,11,12,22

Elevation of the affected limb reduces hydrostatic pressures and improves tissue swelling. It also prevents venom from accumulating in the extremity, potentially reducing local tissue damage.1 Lying with the bite in a neutral position is acceptable in the prehospital setting.12 Cold-water immersion and cryotherapy with ice packs carry their own risks, as prolonged use may result in thermal injuries, and they are not recommended.10,11,12 Some experts believe that prehospital use of ice packs applied for a few minutes at a time (5 minutes on, and 10 minutes off) is safe.11 Marking the edge of tenderness/swelling on the skin, and writing the time alongside, aids in monitoring the progression of swelling and erythema.12

Analgesia is essential. Intravenous opioids are preferred over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as the latter may inhibit platelet function and are not as effective in controlling pain.1,12

Crotalid venom can increase capillary permeability, so although euvolemia should be maintained, caution not to over-resuscitate with fluids is important, as volume overload may contribute to edema and tissue swelling.1 Prophylactic antibiotics have not proven to be beneficial as there is low likelihood of infection, likely due to the proteolytic properties of snake venom.1,6,8,21 Tetanus immunization should be administered if it is not up to date.8

Antivenom

FabAV, known by the brand name CroFab® (generic: crotalidae polyvalent immune fab ovine), is one of two FDA-approved antivenom formulations for the treatment of crotalid envenomations. However, it is the only one approved to treat all North American crotalid envenomations.13

FabAV was released to the market in 2000.9 The formulation is derived from the venom of four North American snakes: Mojave rattlesnake (C. scutulatus); cottonmouth (A. piscivorus); eastern diamondback rattlesnake (C. adamanteus); and western diamondback rattlesnake (C. atox).

As an ovine antivenom, production involves injecting small amounts of venom into sheep to create antibodies that can be extracted and processed to formulate FabAV.9 It should be used with caution in patients with allergies to sheep, latex, papaya, pineapple, papain, and bromelain.9 FabAV has cross-reactivity with a number of species, but there is no well-documented evidence of venom neutralization for the western pygmy rattlesnake.9

Indications for Antivenom

The indication for administration of antivenom include:

- progressive local tissue injury. This is swelling that crosses any major joints (e.g., tenderness, swelling, or hemorrhagic blebs).

- systemic toxicity (e.g., hypotension, airway swelling, or neurotoxicity)

- hematotoxicity (e.g., prothrombin time >15 seconds, fibrinogen <150 mg/dL, or platelets <150,000 cells/μL).1

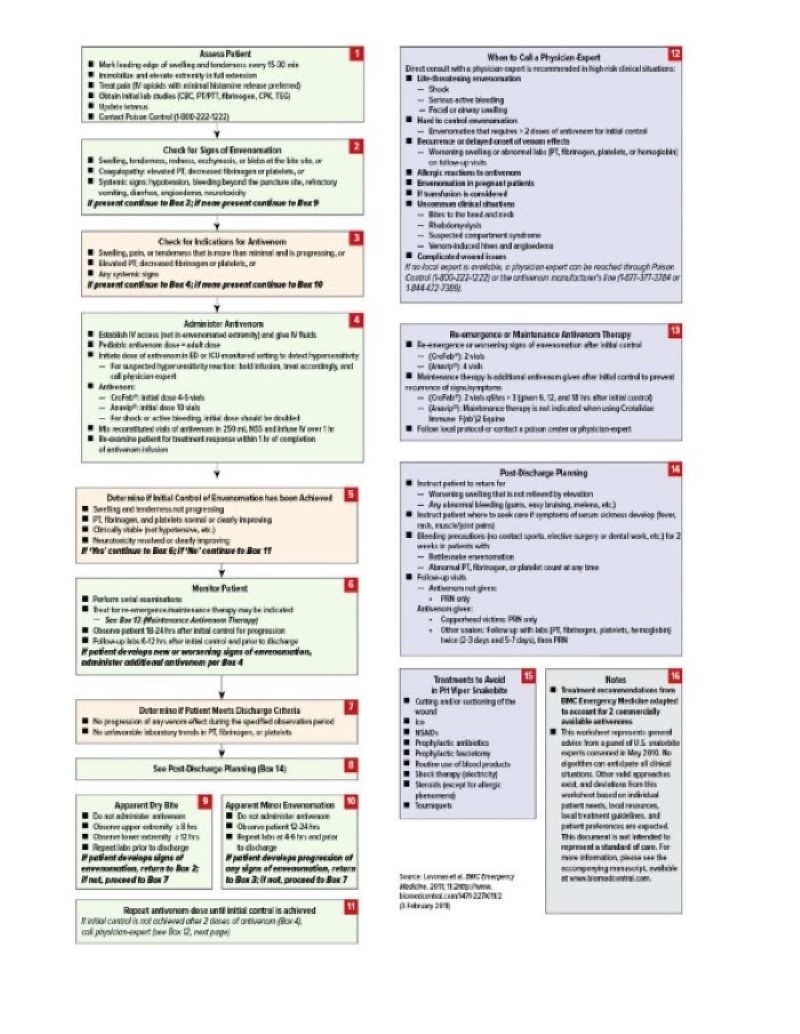

The snakebite severity score was designed as a research tool and has not been validated for clinical decision-making. Reliance on this tool may result in undertreatment.14 Figure 1 shows the Unified Treatment Algorithm for Management of Pit Viper Snakebite in the United States.

Figure 1: Treatment Algorithm for the Management of Pit Viper Snakebite in the United States.

FabAV Dosing

The typical starting dose of FabAV is 4 to 6 vials. If control is not initially achieved, then another 4 to 6 vials should be administered.15,16 However, the initial dose may vary from 4 to 12 vials and is based on clinical judgment and the severity of envenomation.15,16 Dosing is the same for adult and pediatric patients.15

In FabAV clinical studies, “initial control” was defined as stopping progressive local effects and resolution of hematologic as well as systemic toxicity. It was achieved in 67 to 88 percent of participants.15,17

Once initial control is achieved, the manufacturer recommends an additional 2 vials every 6 hours for up to 18 hours (total of 3 doses) to reduce the incidence of coagulation abnormalities due to residual venom.16

Surgical Care

Compartment syndrome is a rare complication from crotalid envenomation.1,8,21 An expert panel of trauma surgeons and medical toxicologists concluded that prophylactic fasciotomy was not beneficial.18,21 The same group of experts stated that even in the rare event of compartment syndrome, initial treatment should be additional doses of antivenom, not fasciotomy, as antivenom is the definitive treatment.18,19,20 Fasciotomy should be considered only in patients with elevated compartment pressures despite adequate antivenom therapy.19

Case Resolution

Our patient was noted to have significant pain and progressive swelling to the left foot. He received 4 vials of FabAV and morphine for pain control. Repeated laboratory testing obtained 5 hours after the bite showed normal platelets, prothrombin time, and fibrinogen. The snake was photo-confirmed to be a western pygmy rattlesnake. Repeated evaluation showed bruising and, very briefly, a rash on the shin. The patient was admitted to the PICU where an additional 6 vials of FabAV were given over 18 hours. The patient’s INR peaked at 1.1, with a platelet nadir at 193,000. He was discharged on hospital day 4 after swelling and color changes stabilized.

Conclusion

Western pygmy rattlesnake envenomations are a rare occurrence. FabAV has cross-reactivity with a number of species, but there is no well-documented evidence of venom neutralization for western pygmy rattlesnake envenomation. Our case highlights a moderate western pygmy rattlesnake envenomation in a pediatric patient — with the development of pain and swelling to a limb — that was responsive to FabAV.

Take-Home Points

- Western pygmy rattlesnake envenomations are a rare occurrence but should not be underestimated, as they cause significant morbidity.

- The indications for administration of antivenom include:

- progressive local tissue injury, which is swelling that crosses any major joints (e.g., tenderness, swelling,or hemorrhagic blebs)

- systemic toxicity (e.g., hypotension, airway swelling, or neurotoxicity)

- hematotoxicity (e.g., prothrombin time >15 seconds, fibrinogen <150 mg/dL, or platelets <150,000 cells/μL)

- The typical starting dose of FabAV is 4 to 6 vials. If control is not initially achieved, then another 4 to 6 vials should be administered every hour until symptoms are controlled. The initial dose may vary from 4 to 12 vials and is based on clinical judgment. The severity of envenomation should be considered, and toxicology should be consulted for recommendations. Once initial control is achieved, administration of an additional 2 vials every 6 hours for up to 18 hours (total of 3 doses) is recommended to reduce the incidence of coagulation abnormalities due to residual venom.

- Antivenom dosing is the same for adult and pediatric patients.

References

- Greene S, Cheng D, Vilke GM, Winkler G. How Should Native Crotalid Envenomation Be Managed in the Emergency Department? The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021;61(1):41-48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed/2021.01.020

- McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Herpetologist’ League. ISBN 1-893777-00-6.

- Klauber LM (1997). Rattlesnakes: Their Habitats, Life Histories and Influence on Mankind, Second Edition. (First published in 1956,1972). Berkeley: University of California Press. 1,476 pp. (in two volumes). ISBN 0-520-21056-5

- Gold BS, Barish RA, Dart RC. North American snake envenomation: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2004;22(2):423-443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2004.01.007

- Kostick N, O'Loughlin K. The Natural History of a Pygmy Rattlesnake Bite. J Emerg Med. 2021 Oct;61(4):e93-e95. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.04.021. Epub 2021 Jun 24. PMID: 34175189.

- Patel V, Kong EL, Hamilton RJ. Rattle Snake Toxicity. PubMed. Published 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431065/

- Lazarovici P, Marcinkiewicz C, Lelkes PI. From Snake Venom’s Disintegrins and C-Type Lectins to Anti-Platelet Drugs. Toxins. 2019;11(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11050303

- Jessica Slim. Snake Bites. Default. https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies-interest-groups-affiliates2/cdem/for-students/online-education/m4-curriculum/group-m4-environmental/snake-bites

- Williams KL, Woslager M, Garland SL, Barton RP, Banner W. Use of polyvalent equine anti-viper serum to treat delayed coagulopathy due to suspected Sistrurus miliarius streckeri envenomation in two children. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017 Jun;55(5):326-331. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1284334. Epub 2017 Feb 6. PMID: 28165801.

- Frank HA. Snakebite or frostbite: what are we doing? An evaluation of cryotherapy for envenomation. Calif Med 1971;114:25-7

- Greene, S. Snakebite Management (pre-hospital). Wild Snakes: Education and Discussion. Published June 5, 2018. Accessed March 5, 2023. https://wsed.org/snakebite-management-pre-hospital/

- Venomous Snakes - Symptoms & First Aid | NIOSH | CDC. www.cdc.gov. Published February 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/snakes/symptoms.html

- CroFab (Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab (ovine)). West Conshohocken, PA: BTG International Inc; 2018.

- Lavonas EJ, Ruha AM, Banner W, Bebarta V, Bernstein JN, Bush SP, et al. Unified treatment algorithm for the management of crotaline snakebite in the United States: results of an evidence-informed consensus workshop. BMC Emerg Med 2011; 11:2

- Dart RC, Seifert SA, Boyer LV, Clark RF, Hall E, McKinney P, et al. A randomized multicenter trial of crotalinae polyvalent immune Fav (ovine) antivenom for the treatment for crotaline snakebites in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:2030-6

- CroFab®. Prescribing information. BTG International Inc.; August 2018.

- Lavonas EJ, Gerardo CJ, O'Malley G, et al. Initial experience with Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab (ovine) antivenom in the treatment of copperhead snakebite. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(2):200-206.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, Dart RC, Khatri V, Lavonas EJ. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013 Oct. 217 (4):726-35.

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Boutsikaris A, Clancy C. Elevated compartment pressures from copperhead envenomation successfully treated with antivenin. J Emerg Med. 2014 Jan. 46 (1):34-7.

- Tanen DA, Danish DC, Grice GA, Riffenburgh RH, Clark RF. Fasciotomy worsens the amount of myonecrosis in a porcine model of crotaline envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 2004 Aug;44(2):99-104. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.009. PMID: 15278079.

- Ruha AM, Kleinschmidt KC, Greene S, et al. The Epidemiology, Clinical Course, and Management of Snakebites in the North American Snakebite Registry. Journal of Medical Toxicology: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 2017;13(4):309-320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-017-0633-5

- Pressure Immobilization After North American Crotalinae Snake Envenomation. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2011;7(4):322-323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-011-0174-2